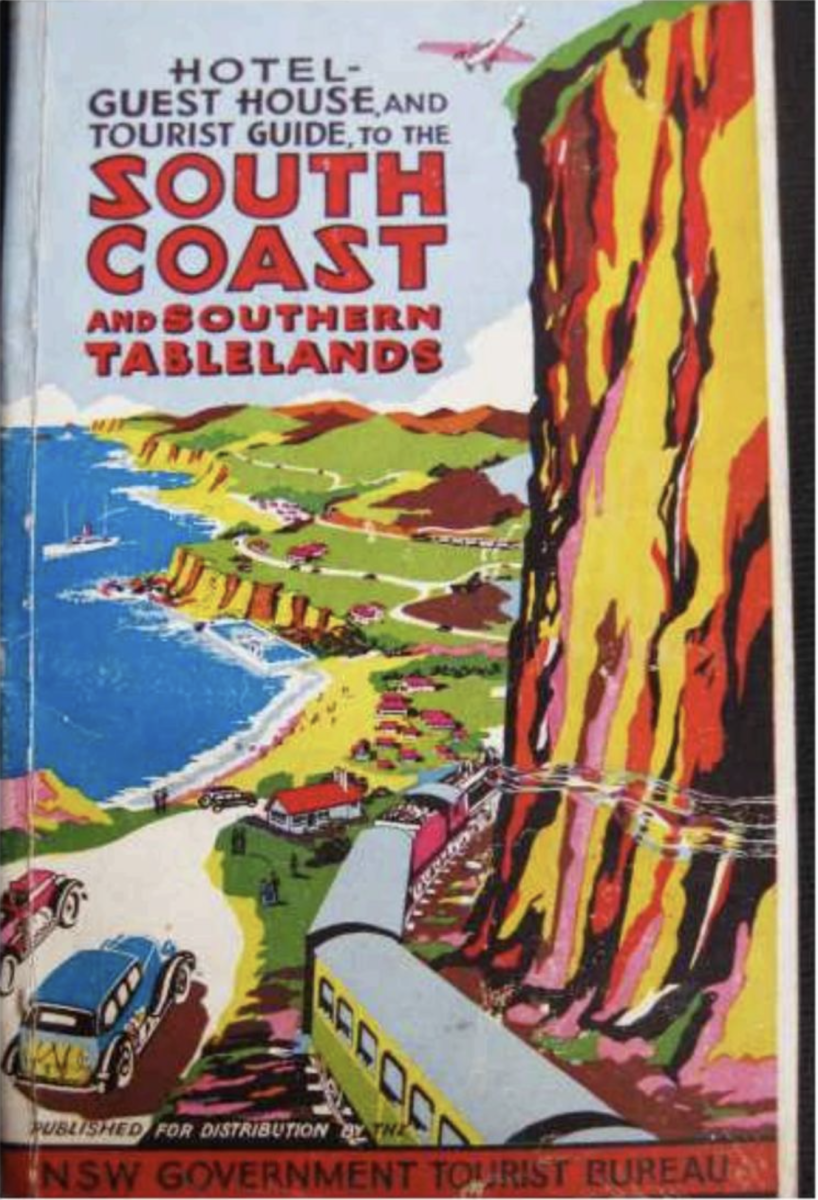

This 1930s NSW Government Tourist Bureau poster appears to be years ahead of its time. Photo: Supplied.

If ever a poster was designed by a soothsayer with 20/20 future vision then this little number might possibly be it.

History, like the study of English literature, is up there with the most pointless of academic disciplines. Regrettably, I have wasted an entire lifetime studying both.

My favourite historian, the American Will Durant, pretty much nailed the problem. “Most history is guessing,” he declared, “and the rest is prejudice.”

The study of literature, however, needs no nailing at all. People who read books about the past, no matter how “literary” they might be, would possibly do better just to get out more.

The only slight value the past might possess is, perhaps, best expressed by the late Professor of English, Daniel N Fader, the author of Hooked on Books.

He reckoned the poorest person in the world is the person limited to their own experience – the person who does not read books.

Unfortunately, Fader never seems to have realised that maybe you could just talk to people rather than read their books.

Fader also reputedly once moonlighted as a librarian employed by an American prison. His job was to get inmates addicted to reading so they had less time to engage in burning down the prison or engaging in general everyday low-level rioting.

The authorities gave Fader three months to be able to demonstrate that his efforts to encourage the reading of books were actually having the desirable impact. At the end of the 90 days the scheduled performance review took place.

“Mr Fader, can you demonstrate to have had a positive impact on any inmates?” “Yes,” replied Fader confidently, “63 per cent of the prison library has been stolen.” There is likely no greater measure of an enthusiasm for reading than felons convicted of robbery willing to risk further punishment by stealing a volume from a prison library.

This story (whether true or not) has always impressed me and hints at why history is so very often incapable of going anywhere near predicting what might be likely to happen in the future.

And so the adage that “those who do not know their history are doomed to repeat it” is up there with some of the most far-fetched fairy tales in terms of demonstrable veracity.

Thus the only kind of history artefact I have much time for these days is the kind that can successfully predict the future.

Recently, I turned up a classic Illawarra example depicting the view from Bald Hill at Stanwell Park. And its virtues are manifold.

Aesthetically, the heightened colour palette even looks forward to the 1980 fluro inks of Wollongong’s Redback poster art produced down in Stuart Park.

And the delightfully varied fonts in which the text is presented would surely also warm the cockles of the heart of the late Steve Jobs.

The multifarious fonts available today on all computers have their origin in the calligraphy obsession Jobs developed after being inspired by a Professor at Red College of Portland, Oregon, named Robert Palladino.

Yet this sweet Illawarra 1930s poster was clearly produced by a printer who, though possessing a well-stocked cabinet of letterpress fonts, would likely have been deeply envious of the extraordinary array so easily available in 2025.

Similarly far-seeing is the poster’s depiction of luxury motor vehicles tackling the downward run of what is now Illawarra’s Grand Pacific Drive.

And how on earth did that 1930s graphic artist know that cruise ships might one day wish to make Port Kembla their regular port of call?

Or that the Shellharbour Airport has expanded far beyond the cow paddock it once was.

No illustrative reader of tea leaves can be expected to get everything absolutely right, but our anonymous 1930s poster artist has pretty much done a whole lot better than could be expected of most historians.

All he or she appears to have missed is the menacing roar of the motorbikes screaming across the Sea Cliff Bridge on weekends and also the infill of every vacant 1930s block of land so that, in 2025, houses crowd forward till living rooms meet – face-to-face at the doorstep of each crowded Illawarra street.

Furthermore, the marvellously elegant steam locomotive conjures up hope that Illawarra’s “Cockatoo Run” train ride will not forever fall into desuetude.

Even Stanwell Park’s most commanding residential view (from the reputed former brothel named “Interbane”) has been perspicaciously updated – although only by some 20 years as a 1950s American bungalow rather than the sympathetic restoration it might well undergo today.

Better still, Illawarra’s northernmost rock pool looks like it has been artistically transmogrified into the world’s largest.

This in itself is yet another admirable prediction (although somewhat askew in regard to its dimensions) of the efforts to address natural erosion and structural issues undertaken by Wollongong Council’s maintenance of Illawarra’s fabulous rock pools.

Clearly, it seems, the best way to predict the future is to invent it.