NSW will switch to managing the presence of varroa mite, after an attempt at eradication. Photo: NSW DPI Biosecurity/Facebook.

Belinda Foley may have had beehives for nine years, but the past 15 months have brought new challenges.

Ms Foley, who sells honey and other bee products through her business, Belinda’s Beehive, said it had been a time of careful checks and worry about the spread of varroa mites.

“It has been a bit scary, because if I lose my bees then I lose my whole business,” she said.

“My cousin was in one of the first areas when it was eradicated, and he had 50 hives that were all destroyed.”

The National Management Group (NMG), which manages the spread of varroa mites, made the decision on Tuesday (19 September) that eradication was no longer feasible.

NSW will now operate under an interim management strategy until a “National Management Plan for Transition to Management” is developed.

NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI) Deputy Director General Biosecurity and Food Safety John Tracey said the interim strategy would see the whole state fall under a suppression zone or a management zone.

“The only management zones will be in the existing emergency eradication zones in the Kempsey, Hunter and Central Coast regions,” he said.

“Free movement will be allowed within management zones, and movement outside management zones will be allowed under risk-assessed permit conditions.

“The rest of the state will be classified as being in the suppression zone, where hive movements will be allowed so long as movement declarations are completed.”

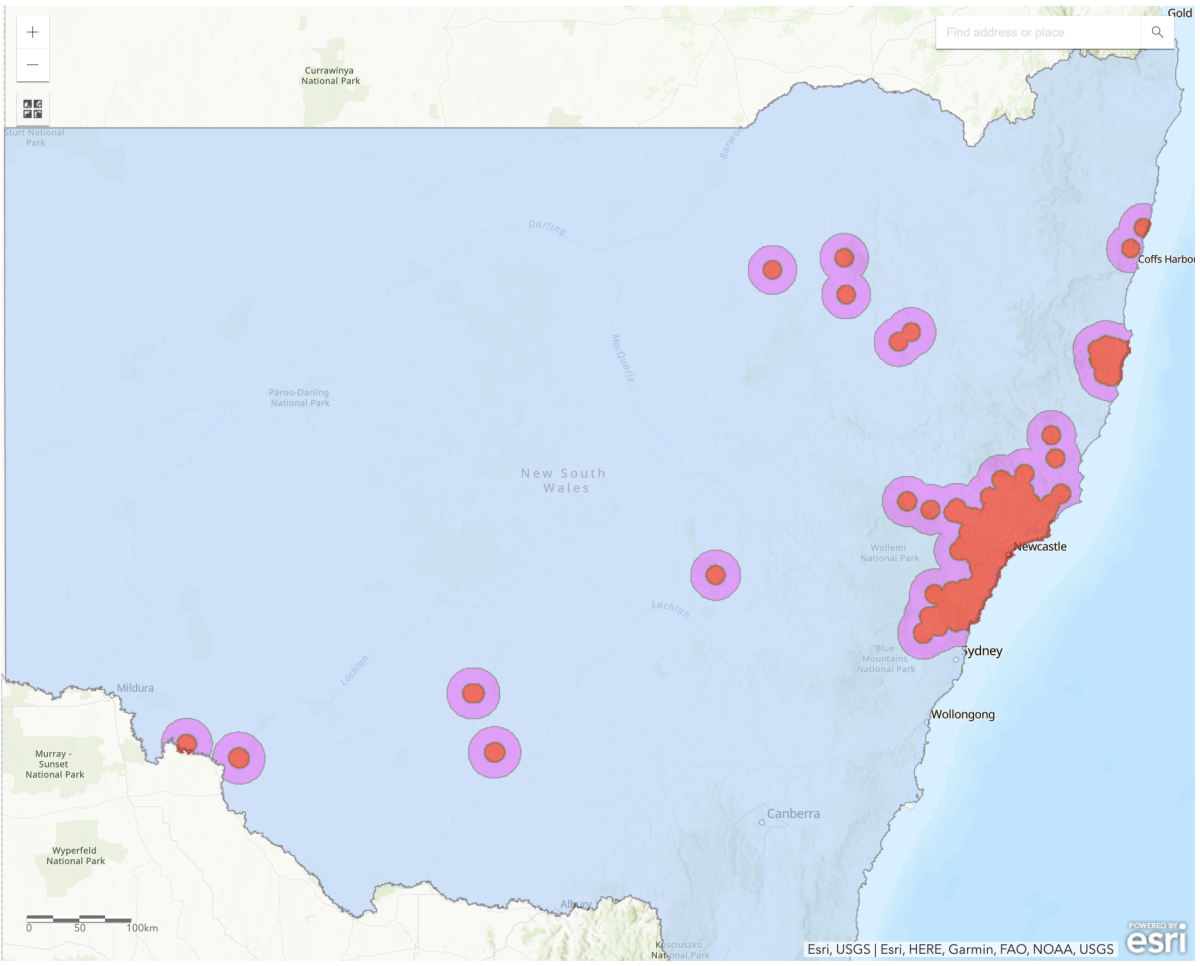

The varroa mite emergency zone map as of 20 September, including the then–eradication (red) and surveillance (purple) zones. Photo: NSW DPI.

The mite was first identified in June 2022 in biosecurity hives near Newcastle.

Before its detection, Australia was the only honey-producing country free of the parasite.

Despite a multi-million dollar eradication effort, it has spread to several locations across the state, including into the Riverina and southeast of the state near the Victorian border.

Trevor Thompson of Trevs Beekeeping in Wagga Wagga, said the decision was the wrong one.

“This mite is a disease that we can get on top of, but I really don’t know why they don’t want to do it,” he said.

“I don’t agree with that decision at all. If you don’t keep on top of the mites, they infest the bees and they end up dying.”

Mr Thompson believed the spread was due to beekeepers moving their hives.

“The biggest problem that we have with the varroa mite is the beekeeper,” he said.

“The varroa mite does not fly. The bees have to be next to each other for [the mite] to spread, or the bees go from one hive to another to another.”

The NMG considered the illegal movement of hives and non-compliance with alcohol washing of hives as factors in the parasite’s spread, according to the NSW DPI.

A spike in recent detections also suggests that the infestation is more widespread than assumed.

According to the DPI, the new interim strategy will see beekeepers still required to test their hives and report results to the DPI every 16 weeks.

Where results indicate a mite infestation, the DPI will provide miticide strips that can be installed in infested hives.

Ms Foley said that under this new approach, beekeepers, large and small, could do their best to keep their hives clean for as long as possible.

“Thank goodness I’m still clean of varroa mites, but I think it’s a matter of time now, really,” she said.

“I’ll just try and keep my beehives away from neighbours’ properties as much as possible, which will protect them a bit more if other bees aren’t around because I cannot stop people getting beehives or other people bringing their hives to the area.”

You can read more about the emergency response on the NSW Department of Primary Industries website.

Original Article published by Claire Sams on About Regional.