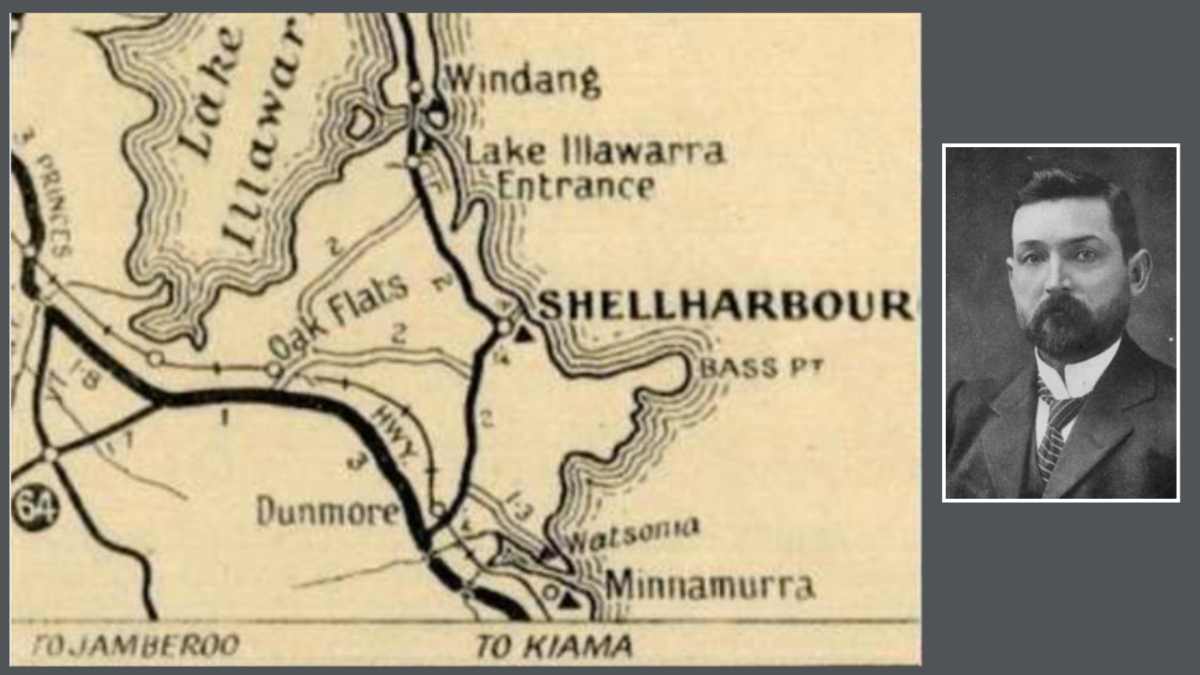

A 1940s NRMA map showing Watsonia and inset, John Watson. Photos: Supplied.

Until sighting the map above, I had never previously heard the Illawarra place name Watsonia. So, as usual, I immediately went into research overdrive.

It turns out that Jamberoo-born Mr Patrick King, of Dunmore – who died in late 1949 at the age of 74 years (and was the son of the late James and Julie King) – had “for the past 20 years occupied the farm Watsonia at Dunmore overlooking Minnamurra River”.

The Watsonia on the map, however, was earlier operated by the National Roads and Motorists Association (NRMA) as a “motor camp” at the northern entrance to the Minnamurra River which, as all the advertising suggested, had a splendid surf beach. The turnoff to Watsonia was from the Princes Highway a quarter of a mile south of the Minnamurra Bridge.

John Christian (known as Chris) Watson (1867-1941) was, of course, the first Labor prime minister of Australia, a position he held for just four months in 1904.

But by the 1920s, he had become a conservative businessman out to make a quid through his political and business connections.

By 1920 Watson had shaved off his distinctive moustache and beard as his hair started to go grey.

He had joined the council of the newly established National Roads Association (NRA) on 22 March 1920 and on 16 August became its president, a position he held until his death.

Watson rebranded the NRA into the National Roads and Motorists’ Association in December 1923, an organisation that seems to have begun with only 20 individuals who guaranteed a bank loan.

Watson steered the organisation as much as if it were a big business as a co-operative that eventually transformed into Australia’s leading motoring organisation.

After his first wife, Ada, died childless in April 1921 the then 57-year-old Watson married 23-year-old Antonia Mary Gladys Dowlan in 1925 and rapidly began expanding his commercial interests.

Most significantly he became associated with George McDonald in Brisbane Metal Quarries Ltd and it may be because of this business connection that he became aware of the land near the blue metal quarries in the vicinity of the Minnamurra River.

Watsonia comprised “an area of nearly 100 acres (40 ha), comprising rich dairying land at the foot of a sloping headland from which excellent seascapes may be enjoyed and a long isthmus, clothed in heavy vegetation, separating one of the finest and safest beaches on the whole of the coast from the mouth of the Minnamurra River”.

It was upon the isthmus that the motor camp was set up.

But when the Watsonia camp got its first review in the May 1928 edition of the Labor Daily it was a shocker: “Is it a fact that Watsonia is only used by members for about three months in the year, and that no family pay a return visit because of the sandflies and mosquitoes that infest the place?”

Watson also became a director of another of F W Hughes’s companies and this company would do rather nicely because of Watson’s position as NRMA president.

Eyebrows were also raised because F W Hughes’s companies (of which J C Watson was a director) received a generous loan from the NRMA.

Unsurprisingly, questions also went public about why the NRMA paid so much for both Watsonia and another property and in May 1928 the Sydney Sun newspaper carried the following headline:

N.R.M.A. STIR

CAMPS FOR MOTORISTS

£24,000 OR £6000?

“PRICES WERE EXCESSIVE”

Messrs Raine and Horne fix the aggregate value at only £6120.

Sir George Mason Allard was then appointed to determine whether there had been any malfeasance. Sir George’s findings were that the price paid was too high but that there was “no improper practice in the transaction”.

Watson himself tried to put some lipstick on the purchase the NRMA had bought by claiming, despite the fact that “only £230” had been derived in revenue from Watsonia, that “the future possibilities of the Shellharbour site … had been abundantly praised by those who had visited it” – that is, I guess, apart from the sandflies and mosquitoes.

Watson was likely fortunate that Australian financial regulators were not that tough in 1928.

But, inconveniently for Watson, he also happened to be a director of the Alexandria Spinning Mills Ltd. And so Watson, at the NRMA annual general meeting, was forced to admit that “the Alexandria Spinning Mills had been given a debenture for £30,000 on £180,000 security, with first call on assets. That was on short call”.

Nonetheless, all’s well that ends well. Watson survived any suggestions of scandal and, apparently, still smelled like a rose (although, perhaps, by now a somewhat faded one).

His survival as president appears to have been that in just three years, the NRMA Insurance Company had made profits amounting to £28,000, and it held assets of over £80,000 against its liabilities and yet it had started with no capital — merely a bank guarantee signed by 20 members.

Clearly financial success talked back then – just as it often does today.