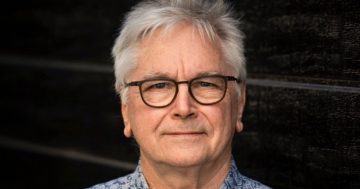

Pip Williams worked with playwright Verity Laughton on the stage adaptation of her book, The Dictionary of Lost Words. Photo: Kabuku PR.

When Pip Williams was approached about having her award-winning book The Dictionary of Lost Words adapted for the stage, she was understandably nervous about handing her words over to another storyteller for reinterpretation.

The selected playwright was Verity Laughton, and not five minutes into their first meeting, Pip was convinced; “My work was in good hands,” she says.

“It’s kind of like handing your baby over to a childcare teacher,” she laughs.

“But Verity had read and listened to the book even before she was approached to adapt it. She talked to me about what she saw in the story, and it was comforting to hear her reflect on the same things that mattered to me when writing it — and more.

“I always say a book is only 75 per cent complete when it hits the shelves — the reader finishes it. In this case, Verity added something from her own experience. It all chimed with what I was thinking when I wrote the story.”

Set in 1886, during the height of the women’s suffrage movement and the creation of the first Oxford English Dictionary, The Dictionary of Lost Words follows young Esme Nicoll.

While her father and his male colleagues decide which words stay and which go, Esme gathers the discarded scraps to compile her own radical, magical dictionary.

Williams wrote the book to answer a few questions she was pondering.

“I was curious about whether words meant different things to men and women and, if they did, was it possible some meanings and words had been left out of the dictionary? It was a very male project, after all,” she says.

“I couldn’t answer the question through research, so I wrote this story to explore it through my imagination.

“As an author, I never questioned the veracity, authority and accuracy of the dictionary. It made me ask – what other revered texts and institutions do we live by without interrogation? Constitutions, education systems, justice systems, workplaces — they can all be questioned through the lens of: who created this, and for whom did they create it?”

While set in the 1800s, Williams says there’s a fairly obvious reason why the play resonates with a 21st century audience.

Many themes in the books — about women’s voices, representation, language and how it’s used — are very current conversations.

“The word ‘suffragette’ was actually an insult coined by a newspaper man in 1906 to refer to women in the WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union) who were starting to ‘misbehave – and act outside the forms of passive protest deemed ‘acceptable’,” Williams says.

“They were described as young women who were probably mentally unstable, with fathers who weren’t taking good care of them.

“At the time I was writing this book, Greta Thunberg was speaking out against climate destruction and the media started describing her in much the same way.

“This is a common theme; when women start standing up and shouting for their rights, the rights of the environment, of children, some segments of society start denigrating those women with insults. Words become weaponised. So unfortunately, these themes the play explores are firmly in the present — they just look and sound a little different.”

The play is masterfully adapted. Fans of the book will find themselves both delighted and, at times, surprised by the stage version.

Even as the author, Williams says the production took her breath away a number of times — such as witnessing the portrayal of the quiet and reflective protagonist, Esme.

“The book is written in first person, and a lot of what happens is going on in her head,” Williams says.

“People underestimate how much work, thought and skill had to go into turning this reflective, quiet character into a character that moves all the action forward. I was extraordinarily impressed by how Verity and her team achieved that.

“There was another moment, during a preliminary reading of the play — a moment from the book I wrote and knew inside out. It was read in such a beautiful, unique way that I cried.

“The first time I saw it at the theatre, I was seated by a woman who didn’t know who I was. She cried in all the right places. As a writer I never get to see the emotions my readers experience when they read my book. To see people engaging with the story is a deeply humbling experience for this author.”

The Dictionary of Lost Words shows at IPAC from Thursday 29 May to Saturday 7 June.