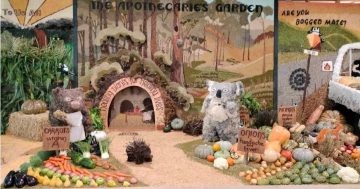

Schools should have nutrition programs to help kids learn about healthy eating habits. Photo: Daniel Vincek.

When former US Tennis champion Serena Williams came out recently touting weight loss injections that helped her lose 14 kg, you could almost hear the stampede for prescriptions.

“They say GOP-1 is a shortcut, it’s not, (pause) it’s science,” she purred in an outdoor advert while sticking a needle into her taut bare midriff.

So, we’ve now gone from failed fad diets to injecting weight-loss drugs in a world where many people don’t seem to get why they are overweight in the first place.

In 2022, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported that 26 per cent of children were overweight or obese – that amounts to about 1.4 million kids. The news was worse for adults with 66 per cent either overweight or obese.

Most of the developed world is scrambling for answers, but I wholeheartedly agree with researchers who believe school-based nutrition programs are the way to go, but they must be more than a token effort and teachers must be properly trained.

It’s always baffled me why the study of nutrition is not taken more seriously in schools by making it a mandated and accredited subject for all students in both primary and high school for at least two consecutive years.

What exists these days is a scattergun approach with some schools doing better than others and it is usually a topic included in a larger subject, rather than making it the bullseye.

Done well, I can’t think of a better place than schools to give kids an early grounding in dietary choice beyond the parental go-to of “it’s good for you”. Children need to know why.

By high school, teens are often choosing their own food so dietary education is even more important in everyday decisions on, say, why a generic chicken salad sandwich with tomato and lettuce and an orange juice (1800 kilojoules) might be a better choice than a Big Mac and medium Coke, which packs a whopping 2700 kilojoules.

And if teens go down the vegetarian route, it’s helpful to understand why rice and broccoli ain’t going to cut it for a balanced diet.

Another reason I solidly back embedding quality teaching in nutrition in the school curriculum is because in the 70s I reaped the benefits of the elective subject known as Home Economics, run by a no-nonsense, well-trained Irish teacher.

We studied in the school’s kitchen every week for two years learning about the science behind each food group, as well as basic cooking.

Our teacher knew her stuff right down to how many amino acids in a complete protein and the unique cellular structure in Choux pastry.

One week, we’d be breaking down the everyday food we eat to its basic elements and the next week we’d be witnessing the wonders of how yeast impacts the bread-making process.

She dubbed me the messiest cook she had ever come across, but I managed to turn out a few decent meals, as well as a robust loaf of bread that the other kids stood back to admire.

I’m still in contact with friends who took that class and we all agree that our sergeant-major-like training has been a lasting gift.

In the world today with endless food choices, bikes that climb hills without pedaling and sedentary indoor gaming, maintaining healthy weight for children is more challenging than ever, but we can’t give up.

To do so seems as silly as teaching kids to read and write without backing it up with the knowledge of grammar and punctuation.

Come to think of it, they tried that a few years ago and look where that got us.