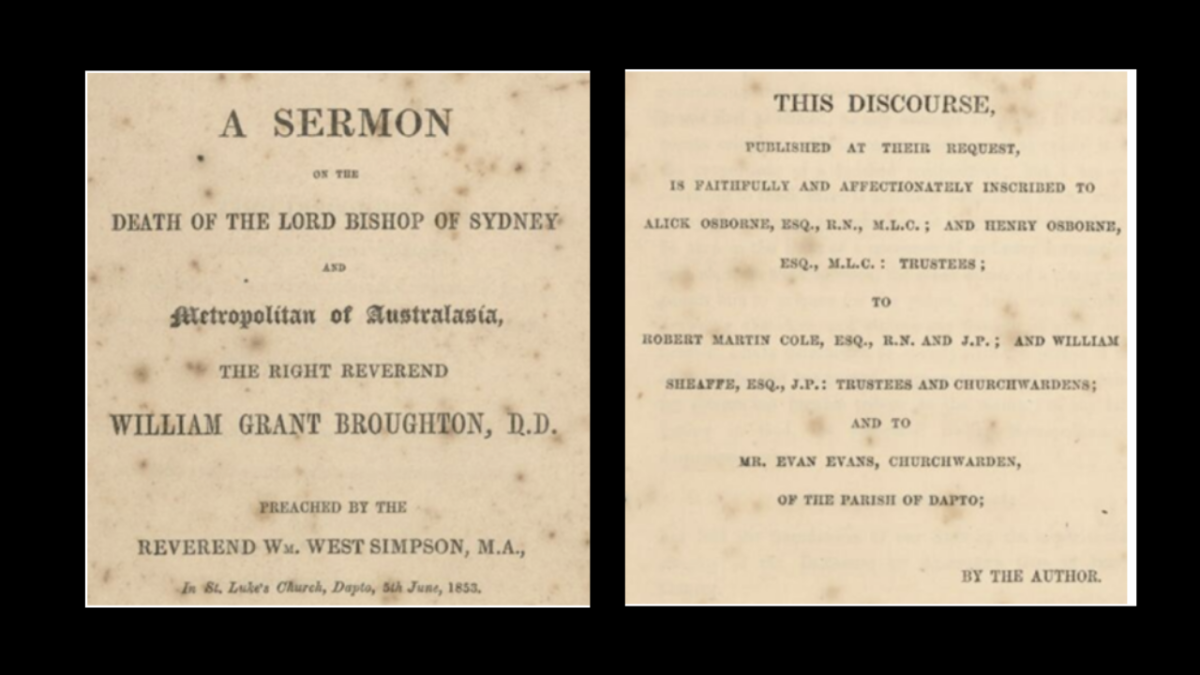

The good Reverend William West Simpson led the sermon at St Luke’s Church Dapto, following the death of the Bishop of Australia. Photo: Supplied.

Some of the good and the great in early Illawarra once lived in Dapto – along, no doubt, with some of the less good. But the difficult question was how could the good and the great get their sons suitably educated without having to ship them off to England.

So in 1830 the Bishop of Australia, William Grant Broughton (1788-1853), established the Kings School at Parramatta offering what was advertised as “a good classical, scientific and religious education to the sons of parents in the middle and higher ranks of life”.

He named it after his old school at Canterbury in England where Broughton was now feted, not quite accurately, as having become the “head of Christianity in a country where education was unknown”.

The Dapto landowner George Brown, among other parents, duly sent son John there but the richest of them all, Henry Osborne of Marshall Mount, demurred and still shipped his second son off to England, even though in 1839 the school had the good luck to briefly get the famous geologist, the Rev William Branthwaite Clarke, to teach.

Although Clarke never lived permanently in Dapto, his fabulous diary contains rare insights into early colonial Illawarra. But, as it turns out, a former headmaster of the King’s School did become a permanent Dapto resident.

The Reverend William West Simpson had become headmaster at Kings in 1848, even though his only title to academic distinction was a Lambeth Master of Arts Degree granted in recognition of a translation of the “Constitutiones Societatis Jesu, Anno 1558”.

And Simpson’s tenure at the King’s School soon terminated when an outbreak of scarlet fever infected him and a number of the boys and he was compelled to resign.

Reverend Simpson’s subsequent clerical appointments finally landed him at Dapto in 1852 where he lived until his death at the parsonage in 1869.

By 1856 the Rev Simpson was listed among the Illawarra’s “most influential and respectable residents” at a giant Freemason’s banquet held at Dapto.

Yet in Dapto, even Simpson’s conduct of simple local marriage services did not always go to plan.

A highly respectable young man had won the heart of a fair damsel residing at the Cordeaux River, so the Reverend Simpson was spoken to and the day was fixed.

One portion of the arrangements was that the intended bridegroom should visit the intended bride’s family at her father’s house the night before the happy day.

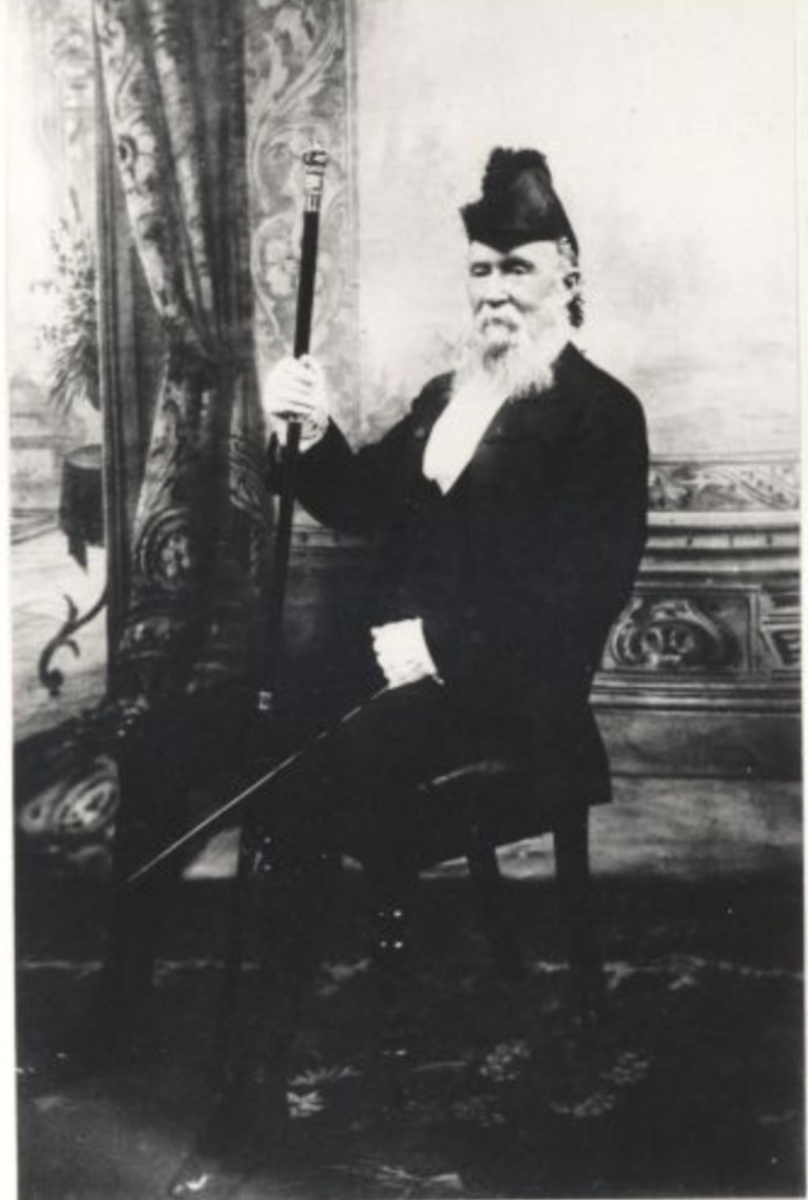

Rev Simpson’s son-in-law Stewart Marjoribanks Mowle who was the NSW Parliament’s Usher of the Black Rod. Photo: Supplied.

But on his way to keep this appointment the young lover fell in with a number of “jolly young bachelors” who insisted upon his spending the evening with them. And so it was not until small hours of the morning that the bridegroom could tear himself away – far too late to visit his bride’s home.

The next day the Reverend Simpson was prepared but no bride appeared. After half an hour, still no lady love hove in sight so the anxious bridegroom rode off for the home of his intended at the Cordeaux River.

There his lady love frowned and scowled, the father stamped and stormed, the mother raved and scolded and the brothers of the young lady threatened vengeance.

Somehow the bridegroom appeased their wrath and the couple was soon on horseback flying down the road towards American Creek and from thence to the Dapto Church, arriving at half past 12.

Here the Rev Simpson, a stickler for protocol, informed the lovers that “ecclesiastical usage” prevented him from “performing the marriage ceremony after noon”.

Fortunately, the reverend had better luck with his own daughter’s marriage to Mr Stewart Marjoribanks Mowle, who became Usher of the Black Rod in the NSW Parliament.

Mowle became aware that in many languages there is a significant difference between an English-like “t” or “d”(when treated as equivalent in Indigenous languages) and one that is pronounced with the blade of the tongue against the upper teeth. It might sound something like the “dth” in width.

Early white recorders in the Illawarra variously heard the sound as a normal “d” or “t”, a voiced “th” as in the words “this” and “bathe” or, rather, requiring a special un-English notation resembling “dh”.

Mowle argued that the town Tumut should be “Dumudth” and also recognised what the Illawarra Mercury editor Archibald Campbell MLA was trying to capture when he transliterated the local places named “Dthirrawell, Dthroon and Dthuroon” (for Thirroul) and “Dtheera” (for Keira).

In 2023 it was suggested the name Mt Keira might be changed to “Djeera” which some think is a better transliteration of what is presumed to be the original Indigenous word.

Stewart Mowle, however, might have argued that a closer transliteration might be “Dtheera”.

But, whatever happens, I guess it’s not much of an issue if a change is made from what might be one poor transliteration for yet another.