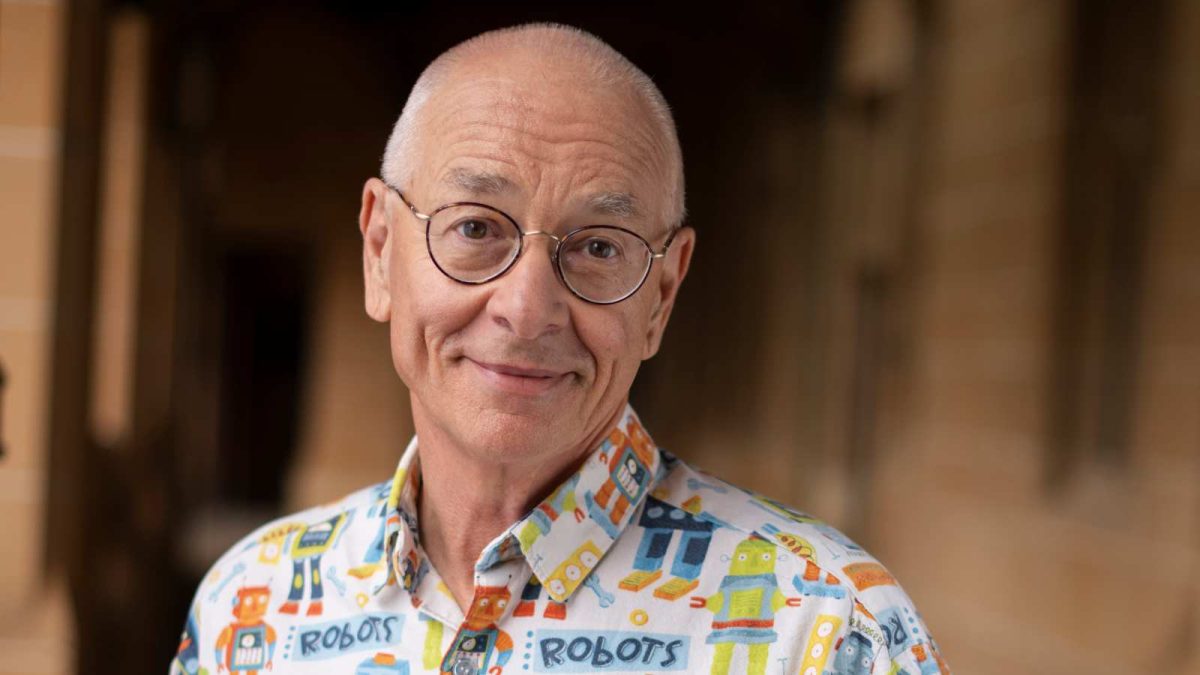

Let us introduce you to a Dr Karl before he wore iconic shirts. Ross Coffey/University of Sydney.

You might not know it, but before he was Australia’s most beloved scientist, Karl Kruszelnicki was a refugee kid growing up in Wollongong.

Dr Karl, as he’s affectionately known around the country, has lived many lives, from taxi driver to music videographer to children’s hospital doctor.

But his story began in refugee camps, first in Sweden, then Australia, before his parents made their home in Wollongong when he was about four years old.

“The worldwide trend is refugees take crappy, poorly-paid jobs, have a very low crime rate and want their kids to do better than them,” he said.

“So I never doubted that I would go through school and go to university.

“Interestingly, by my children’s generation, refugees’ descendants have the same crime rate as the rest of society.

“If you want to bring down the crime rate, bring in refugees and their children.”

A conversation with Dr Karl is peppered with fun facts like this.

He has an endlessly applicable store of sourced information that he shares without thinking twice.

One-on-one he is very much the same person you hear on the radio or see on TV – warm, curious, enthusiastic and energetic.

He said growing up in Wollongong as a child of refugees wasn’t easy.

Luckily, his family had the support of good friends, one of whom encouraged a young Karl to consider a career in medicine.

“My parents had a doctor friend who would visit us every Easter,” Dr Karl said.

“One year he asked, ‘Why don’t you become a doctor?’ and I said, ‘Oh, no, I don’t like blood’.

“That was how shallow my understanding was; I knew nothing of the health system, and I wanted to take things easy to some degree.”

For a young Karl, taking things easy meant pursuing the subjects he was best at in school – science and mathematics – at the University of Wollongong.

Despite doing poorly in his undergraduate studies, Dr Karl said he got another kind of essential education at UOW.

“UOW was liberating – I had grown up in a boys school and then there were all these creatures I knew I lusted after but didn’t know how to talk to,” he said.

“I was trying to get some social training so I hung around in coffee lounges having exotic things like coffee from an espresso machine and cheese on toast.

“I was also getting a world view. I protested against nuclear weapons at 16.

“On three occasions the human race avoided total obliteration because military officers decided to disobey protocol and not set off the chain that would lead to the big red button.

“I also protested in favour of Indigenous people being counted in the census which seemed a terribly basic thing.

“I combined all that with doing very badly in my studies.

“I did well in school because the brothers (at the Christian Brothers School) would hit you if you didn’t; when I arrived at uni no-one was there to push me and my marks plummeted.”

Dr Karl graduated with a degree in physics, and when he was 19 went to work at the Port Kembla steelworks.

It gave him an education of another sort.

“I spoke to a woman who told me she got paid 80 per cent of what I got paid, and I did nothing about it,” he said.

“In retrospect I’m ashamed of that. It was a very black and white patriarchal world then.”

When he was asked to falsify documentation, however, Dr Karl decided he had had enough.

He left the steelworks to work on a research project in Papua New Guinea before he returned to Sydney and took on the most varied time of his career.

“I tried being a drug-crazed hippie, a taxi driver, T-shirt maker and mechanic before I got back into academia,” he said.

“This time I studied really well, and during my time as a mechanic I realised I liked making stuff, so I got a job in a hospital as a science officer where I was blown away by the magnificence of the human heart.

“Before that I thought inside the human body was filled with lumpy red salsa.”

Dr Karl then studied to become a biomedical engineer, and was employed by the late Professor Fred Hollows to build a machine that picks up electromagnetic signals off the human retina to diagnose eye disease.

It took two years, but he made it, then returned to uni to study medicine, dropped out, re-enrolled and worked as a doctor in a children’s hospital.

He didn’t know it, but this would be the experience that inspired his career in the public eye.

A young child on his ward died of whooping cough because their parents did not get them vaccinated, a decision Dr Karl attributes to a TV program that equated expert opinions on vaccines with the opinions of lay people.

He couldn’t bear to watch another child die of a preventable illness, and felt he could do more to help by combatting misinformation.

Forty years later, he’s still one of the most popular homegrown talents on our TV screens and our radio waves, and one of Wollongong’s greatest success stories.