A most significant Illawarra breastplate – very fittingly without a string to hang around the neck – and first illustrated in Poignant Regalia: 19th Century Aboriginal Breastplates and Images published by the Historic Houses Trust of NSW, 1993.

Turning 50 is often a big deal. Either the end is nigh or, if you’re lucky (or perhaps unlucky as the philosopher Schopenhauer seemed to have believed) you might have another 50 years left in you.

Yet, fortunately, in order to sometimes to get a few laughs a historian only has to quote some of the ridiculous things that get reported in the Australian press – as occurred in 1909 when Wollongong’s Municipal Council celebrations “honoured” the 50 years since the town was first incorporated as a municipality.

So here goes.

As reported in the Illawarra Mercury on 25 January 1910: “To celebrate the Wollongong Municipal Jubilee, they had a procession … about a mile long … There was a very excellent town band, the local artillery, the lifesaving brigade and the unnamed Oddfellows. There was also a Tom Thumb boat, called after the 8-foot boat that Flinders and Bass came down the coast in.

“And the first prize went to a cart of ‘Pioneers’ who showed how they went to market in the ‘old times’ sixty years ago The judge told me that the reason he gave them the prize was because they had a good idea, and had worked it out well, and one of the women pioneers had ‘taken’ out her front teeth just to show how the poor people had to suffer in the old times And she laughed — as they used to do — and showed the place of the missing incisors.”

There was also a Jubilee Week children’s picnic with the Wollongong and Keiraville schools given a holiday to attend. There was even a concert with both a choir and orchestra and a swimming carnival in the afternoon in the ladies’ baths.

Things began to be set-up to go bung, however, when as early as November 1909 it was announced that “the coronation of a native king” – William Saddler – would take place. The event was advertised as “not the least of the interesting spectacular effects” planned for the celebrations.

William Saddler, however, was a surprising choice for in 1892, he had condemned the local politicians for renaming the northern Illawarra suburb of Robbinsville with what he said was the meaningless word “Thirroul”.

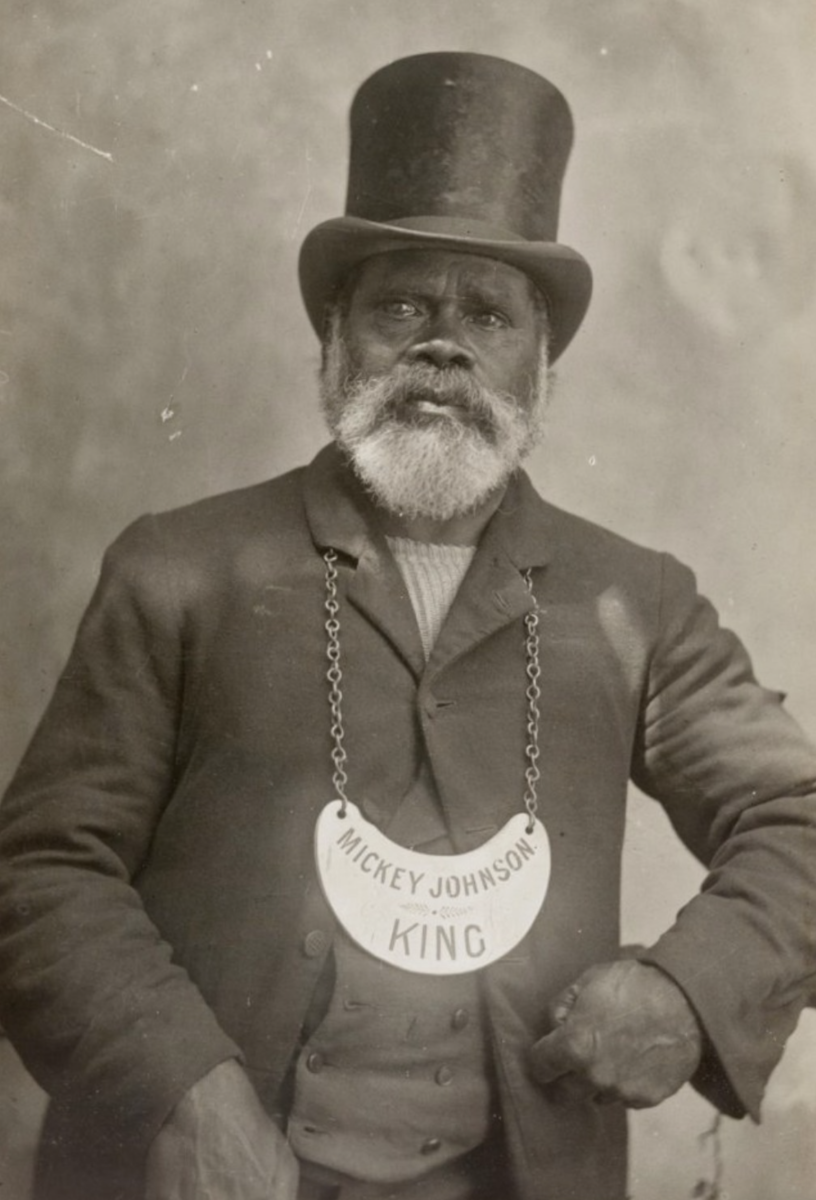

William Saddler chose a far more dignified approach, unlike Mickey Johnson who, whether under duress or not, submitted to the humiliation of being “coronated” as King of Illawarra, complete with suit and top hat, back at the 1896 Wollongong Show’s commemoration of the centenary of Bass and Flinders’ supposed discovery of the Illawarra.

King Mickey Johnson at the 1896 commemoration of the Bass and Flinders’ discovery of the Illawarra. Photo: Shellharbour City Library.

Unintentionally and ironically, the planned coronation of William Saddler turned out to be one of the most spectacular “effects” of all.

For William Saddler was no fool. Once again, there is no need for the historian to explain what happened, as the contemporary press pretty much said it all.

On 28 January 1910, the Mercury reported: “There was a gathering near the beach, where a native king was to be crowned. It was an enormous gathering of ‘honest men and bonnie lasses’, but the king never appeared … Billy (William Saddler) skipped for the scrub and I daresay he was wise. But the Mayor was not a bit nonplussed. He turned on the band to discourse sweet music, and then made a whole lot of fellows make speeches. They were mostly Mayors of other municipalities.”

That night a banquet for these dignitaries was held and to which William Saddler was unlikely to be invited.

The Mercury report continued: “The Mayor (J A Beatson) was supported on one side by a Roman Catholic priest (a real jovial soul) and on the other side by an Anglican clergyman … The ‘dissenting’ clergy were scattered all over the place. There were mayors and aldermen and local Government people on every side … But the speeches. Great Scott! They talked about Wollongong and finance and municipal progress for nearly three hours, right on end. There was no sense of humour visible. They were in deadly earnest.”

So, in choosing not to be patronised, William Saddler must (at the very least) have managed a very big private smile. And, to add to the fun, the unwanted and forlorn breastplate with which the good and the great of Wollongong had specially manufactured for him survives to this day and can be seen above.

I suspect that Billy Saddler well understood that every life contains its share of humiliation but, as that famous German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) argued, “what counts is how we respond to it”.

And like William Shakespeare who wrote a play about a completely different monarch – King Henry IV of England – Illawarra’s William Saddler, appears to have known far better than the good burghers of Municipal Wollongong that “discretion is the better part of valour”.

My guess is that, in avoiding the highly dubious honour Wollongong wished to bestow on him, William Saddler came up with one of the most appropriate dramatic performances Illawarra has (n)ever known.