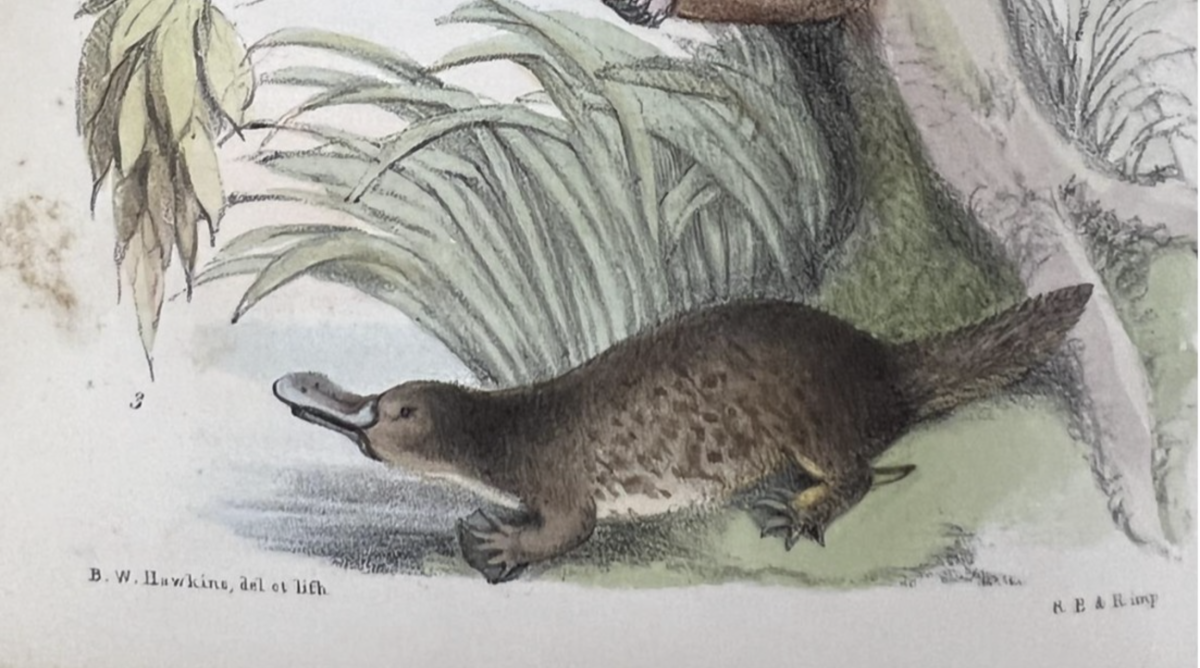

An illustration from Adam White’s A Popular History of Mammalia, published in London in 1850. Image: Supplied.

Region Illawarra recently reported eDNA technology had found evidence of platypuses in Macquarie Rivulet, Reed Creek, Robins Creek and Mullet Creek, around the Dapto area. However, their future may be affected by the massive developments proposed for West Dapto. The story reminded me of the following article I wrote some years ago, which still stands today.

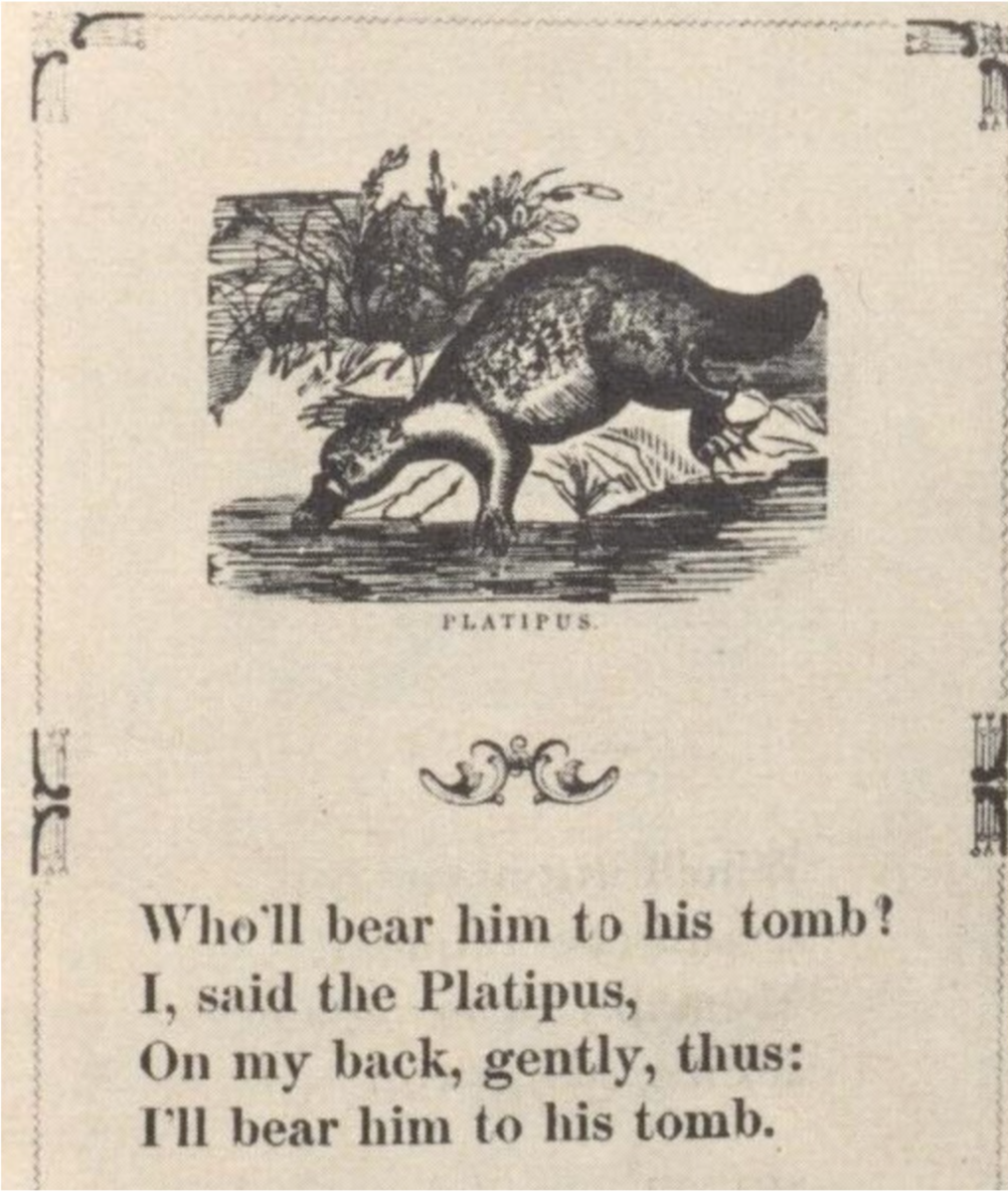

A poem and illustration from a rare little book, Mother’s Offering to her Children, published in Sydney in 1841 possibly makes some kind of oblique prophetic allusion to the fragile hold the platypus today has in some waterways of Australia.

“Who’ll bear him to his tomb?

I, said the Platipus,

On my back, gently, thus:

I’ll bear him back to his tomb.”

The book was said to be by “a lady long resident in NSW”, but she was actually Lady Gordon Bremer, née Wheeler, widow of the Reverend George Glasse. Lady Bremer seems to have left Australia in 1849.

As revealed in a 2024 Land and Environment Court case, platypus have managed to survive near Calderwood in the Illawarra’s Macquarie Rivulet.

While it was contended that no evidence of any platypuses could be found, it was also argued that “the records” of sightings of platypus in this area “from the past 20 years are attributed to community fauna surveys, or ‘citizen scientists’, and as such are considered unreliable”.

One local citizen scientist, however, inconveniently produced video evidence of the presence of the platypus.

So, as is my want, I wondered how well-documented were sightings of platypus in the Illawarra in the first 150 years of white settlement. It turns out that as late as 1928 platypus could still be found in several local creeks and not just at Macquarie Rivulet.

Remarkably, in the same year, a large platypus somehow even found its way into Wollongong’s Continental Baths but was said to have been “allowed to escape”.

The reference to a “platipus” in the 1841 book, Mother’s Offering to her Children. Image: Supplied.

Sadly, some 70 years earlier the fur of the platypus was considered by some to be a desirable fashion accessory. A woman travelling between Berkeley and Wollongong in June 1871 advertised that her platypus muff (a cylindrical covering with open ends into which the hands are placed to keep them warm) had been lost and requested that the finder return it to the Berkeley branch of the Bank of NSW.

But so little were platypuses then understood that as late as 1886, the Royal Society of NSW offered both the society’s medal and a prize of £25 to anyone who could produce a scholarly study of the “Anatomy and Life History of the Echidna and Platypus”.

Meanwhile, the fur of the platypus was still contributing to the demise of the creature and in 1896 one writer declared “the platipus, which lives mostly on eels, has a beautiful skin, softer than a cat’s”.

Still it took until 1905, under the provisions of the Native Animals Protection Act, for the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) to be declared “absolutely protected for seven years”.

Fifty years later, in September 1954, Mr D Allen of Woonona was fishing for bream in the Macquarie Rivulet with Mr C Fursey of West Wollongong when an animal crawled up the small bank between them.

According to a report at the time, Mr Allen originally took it for a rat but “to his surprise noticed it was a platypus”. So he “grabbed the duck-mole behind its head” and “bundled it in a bag”.

Touching a platypus is potentially dangerous if attempts are made to handle the animal in the wrong spot, as the platypus is one of the few living mammals to produce venom.

Moreover, the composition of platypus venom appears to contain a unique cocktail of proteins and peptides which can cause nausea, swelling and excruciating whole-body pain that lasts for weeks in humans and cannot be alleviated by morphine. No antivenom is available.

Yet, despite the excruciating pain, there are no records of platypus venom to date resulting in human deaths.

Nonetheless, surely any surviving platypus in the Illawarra’s Macquarie Rivulet deserve the highest levels of protection.

Local environmentalists find it hard to believe that increasing residential development along the banks of the Macquarie Rivulet can improve water quality and so help provide sustainable platypus habit.

Over the past 30 years, platypus habitat nationwide has shrunk by at least 22 per cent, involving a loss of area almost three times the size of Tasmania. Platypuses are listed as vulnerable in Victoria and endangered in South Australia.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature has upgraded their status to near threatened.

In my view, all South Coast councils, some of which have specific jurisdictional control over parts of the Macquarie Rivulet, need to develop a clear platypus habit management plan for all areas they control.

Management of platypus habitat currently falls under private ownership in the Illawarra, however, is likely to remain an even greater challenge than developing a council-wide management plan.