The Cleveland farm of Thomas Jesset near Dapto. A lithograph from the artist George French Angas’ 1847 book, Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand. Photo: Supplied.

George William Paul, appointed superintendent of the Carters’ Barracks which was built to house convict gangs working as carters on the nearby Sydney brickfields, was granted some Illawarra land near Dapto.

Ironically, between 1835 and 1843, Carter’s Barracks became a debtors’ prison. And, like so many of the bigwigs brought to the bankruptcy courts in the major economic depression of the early 1840s, an apothecary who styled himself as “Dr Thomas Jesset” found himself insolvent.

But so many important people in NSW became bankrupt during this period that a new bankruptcy law – the 1841 Insolvency Act (dubbed “Burton’s Purge” after its author William Burton) – enabled quite a few to get mostly off the hook.

So Jesset was given a “Letter of License” by his generous creditors and was able to abandon being a Sydney chemist selling a little opium and try his luck at establishing an Illawarra farm in 1845 at “Cleveland” near Avondale.

Getting out of the chemist trade was likely a handy escape for the so-called Dr Jesset, for not only did he find himself insolvent in 1841, but upon the death of one of his customers, a coroner declared he “regretted exceedingly that there was no law in the colony to restrain apothecaries from dispensing medicines except from the written prescription of a physician”.

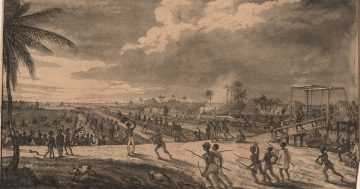

Yet, despite all this, by July 1845 a today famous English-born artist – George French Angas (1822-1866) – was given a letter of introduction to Thomas Jesset and the artist then made the difficult trek down to the Cleveland property.

“Pursuing the road to Dapto, along this rich vale … the sun had disappeared behind the mountain and the purple of evening settled over the landscape before we arrive at our destination … a light gleamed from the loft or upper story of a barn … we ascended a steep flight of wooden stairs to partake of the hospitality of our host, in the temporary shelter which was afforded his family in the upper loft of his capacious barn … [where] the spirited settler in the wilds of Australia must undergo privations that are unknown at home [in England].”

So the theoretically still-indebted Thomas Jesset was found living rough at Dapto in 1845.

The Old Cleveland Homestead c1981. Photo: Anne C. Ali, Wollongong City Libraries.

Cleveland eventually fell into disrepair. Photo: Mick Burns, Dapto History in Photos.

But, as artists often can, George French Angas was able to see (or at least imagine) beauty in the farm Jesset hoped to create and put it down in watercolour.

Angas also worked up another two rather lovely Dapto images in 1851 that are today held by the National Library of Australia.

Some years later Thomas Jesset’s growing of hops at Dapto reputedly made him quite a reasonable amount of money – at least according to an early Polish immigrant to Illawarra named Ignacy Zlotkowski.

Hops, of course, were useful in another drug by giving beer both its bitterness and a distinctive aroma along with the added bonus of acting as a preservative.

Apparently, so good was Jesset’s gardening chemistry that at the December 1848 Australasian Botanic and Horticultural Exhibition, the gold medal for hops went to “Dr Jesset, of Illawarra” for “a very fine sample”.

But whether it is true or not that Jesset’s hops brought him financial gain, Thomas Jesset does seem to have done well out of the gold diggings further down the coast at Araluen.

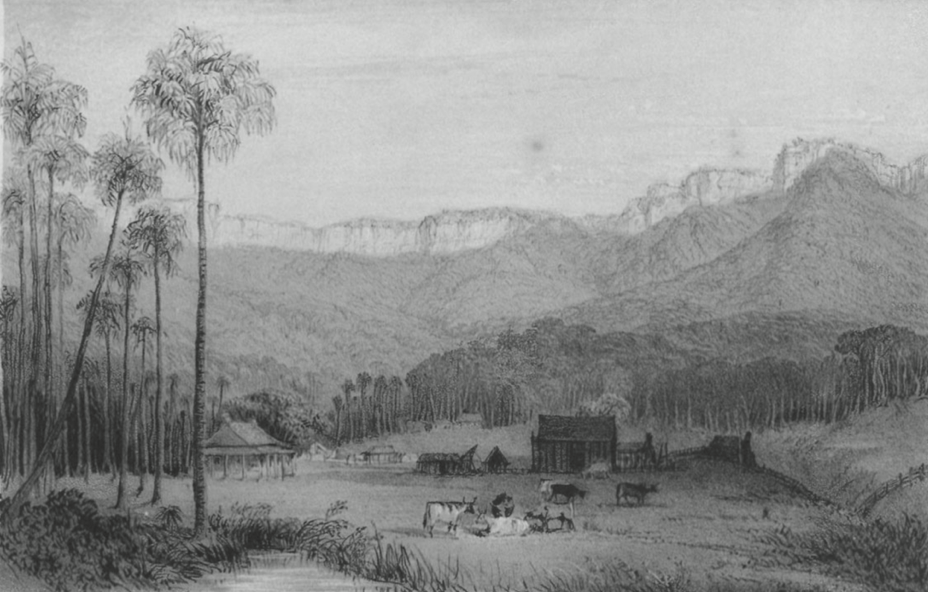

So near Dapto, Jesset was able to build his Cleveland homestead – a once reputedly lovely single-storey house built in rendered Flemish bond brick.

The front elevation had five pairs of French doors, all similar, the verandah a bullnose roof and all the joinery was fine Illawarra cedar.

Yet, despite all this, in January 1854 “Dr and Mrs Jesset” sailed for London and the farm then went through a succession of owners.

The Madden family of Thirroul purchased the Cleveland property in the late 1880s and even managed to gain second place in a rich prize offered for the best kept farm on the south coast.

Sadly, a century later the Cleveland homestead near Dapto was in disrepair and ended its life as an almost complete ruin.