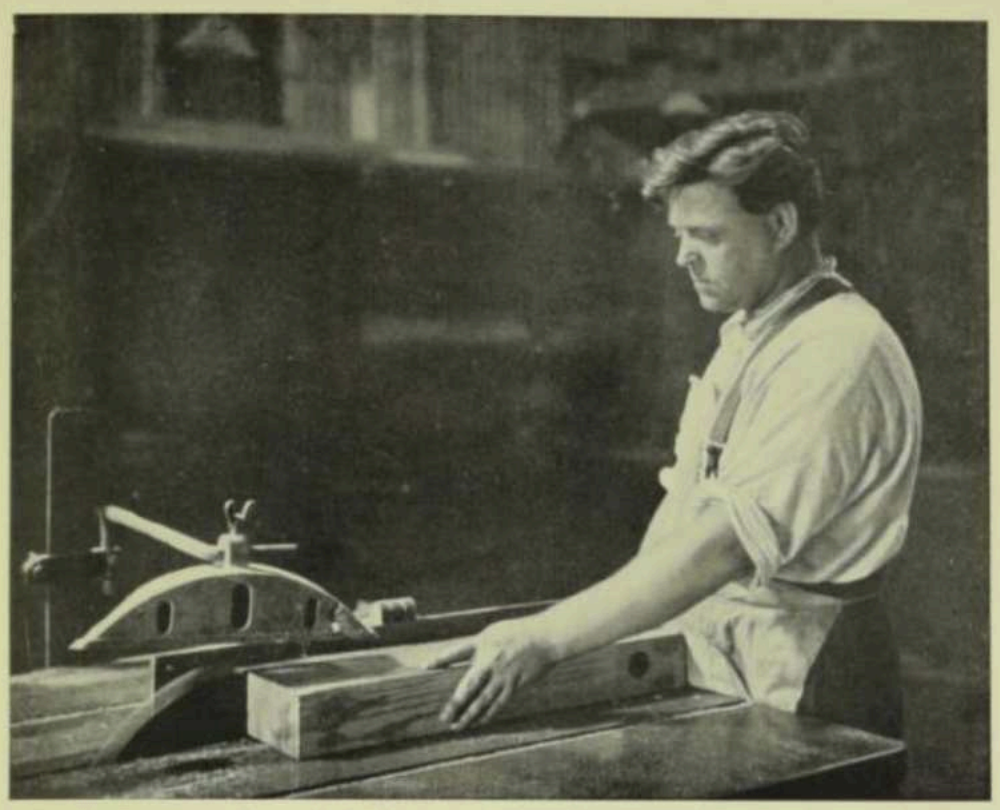

The caption on this George Oyston photo which appeared in the Australian Photographic Review in 1922 says: “The saw bench. Taken about noon in a carpenter’s shop, lit from skylight and side windows. Austral Orthochromatic plate, lens aperture f/7.7 exposure about 6 seconds. Geo. Oyston.” Photo: Supplied.

I had originally hoped that this photo above might have been a very arty self-portrait, but now believe George Oyston simply chose the best looking bloke in the carpenter’s workshop at the Mount Lyell Coke Works at Port Kembla.

Despite the fact that it’s become pretty obvious that most Wollongongers don’t mind taking a quick glance at an old photograph or two of their local area, I am continually surprised at how little interest people display in the person who might have gone to the trouble of producing the image.

Wollongong Reference Library, for example, holds at least 68 images catalogued under the name “George Oyston”, yet no-one appears to have bothered to find out who he was.

This usually matters little, but, in the case of George Oyston, the collection of images held by Wollongong Library (and their otherwise laudable online reproduction) actually misrepresents the Oyston oeuvre.

As it turns out, although often describing himself as an “amateur” and usually practising as what might be termed a kind of “Sunday photographer”, George Oyston Junior was a serious photographic artist.

What’s more, and this is especially unusual, Oyston’s photographs were reviewed and criticised at some length in publications within Australia.

Such things are uncommon for even famous Australian photographers and so the purpose of this present little study is to reveal some of the highly artistic images Oyston produced – images that raise him far above the general run-of-the mill when it comes to early and mid-century Australian photographers.

His first known surviving photograph is of a procession at Bulli held on 4 July 1913 to celebrate the coming of electric lighting to the main streets of Woonona, Bulli, Thirroul and Austinmer.

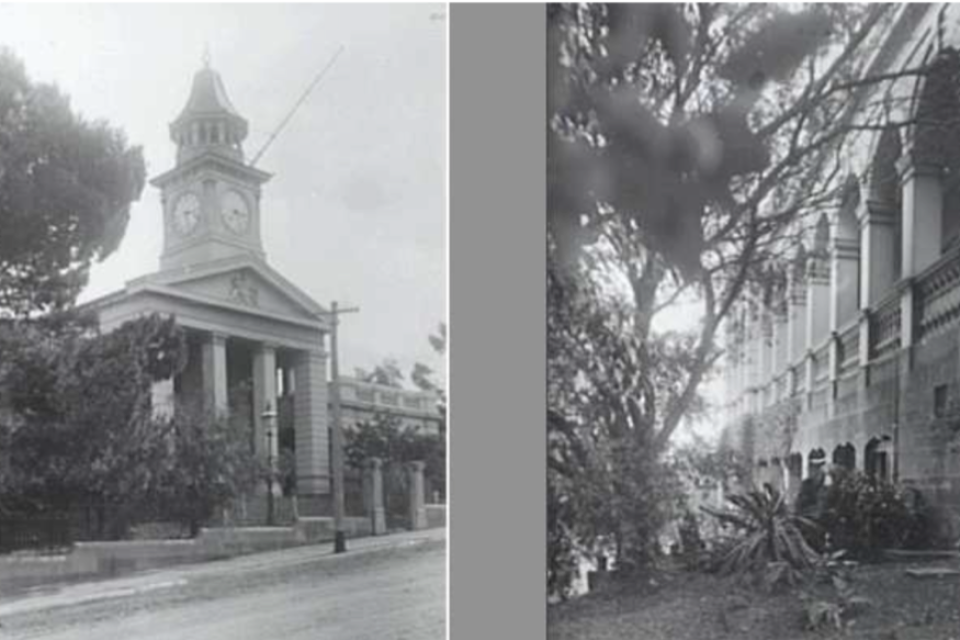

Other early photos include steeplejacks at Port Kembla and a pair of fine shots that make the Wollongong Court House look suitably elegant.

Oysten’s grandfather was born near Crook in County Durham about 1805. Crook, originally an agricultural area, is about 14 km from Durham itself. It began to thrive as a mining village because of coal and soon there were more than 20 mines in the vicinity.

Unsurprisingly, George’s father – George Senior – grew up to work as a coal miner but the ship’s indent for the Norbudda on which the family emigrated to Australia in 1883 described George Senior simply as a labourer.

It was a tragic voyage carrying 432 passengers. A severe outbreak of measles occurred and 17 children died. George Senior travelled with his wife and three children – Abraham, Doris and John Robert – the latter dying at sea on the voyage aged only about four years old.

Worse still, his wife was pregnant and she delivered a female baby on board. The child died the same day. The Norbudda reached Sydney on 30 March 1883 and Oyston’s wife was dead four days later.

How George Oyston Senior coped and where he first stayed with his two now motherless children is unknown. His troubles appear to have been such that, for some reason, no-one appears to have got around to registering the death of his wife.

But within just two years George Senior remarried to Martha Mann and he was back to working as a coal miner, but this time at Bulli Colliery.

Their first daughter Elizabeth was born in 1885 (registered at Woonona) and George Oyston Junior was born in 1889, also registered at Woonona.

A daughter, Martha, was born in 1894 after the family left Bulli.

George Senior appears to have worked at the new Dapto Smelting Works at Kanahooka that boomed for a few years, treating lead, silver, zinc and gold.

But when the ludicrously chimerical Lake Illawarra Harbour project failed to eventuate, the Kanahooka works closed and a new smelting project eventually began at Port Kembla in the new century.

From a population of some 500 during the smelting boom, Kanahooka and Brownsville became virtual ghost towns and reverted to traditional dairying. George Oyston Senior then gained employment in the early days of Wongawilli Colliery in late 1896.

Oyston Junior’s best photographs are absolute knockouts and some are as technically impressive as the works of the great Harold Cazneaux.

The great regret is that George Junior was not from a more wealthy family – as I suspect if he had the chance to risk his hand he could have been a photographic artist at least as significant as Cazneaux.

In 1914 Cazneaux had won Kodak’s Happy Moments contest and used the £100 prize as a deposit for a house in Roseville where he lived and worked from 1920 for the rest of his life.

Frustrated and in poor health, he had quit his job to become a full-time photographer and was only rescued from penury by Sydney Ure Smith, who gave him regular work for his new publications The Home and Art in Australia.

If only George Oyston Junior, who died on 11 June 1962, had found a similar patron.