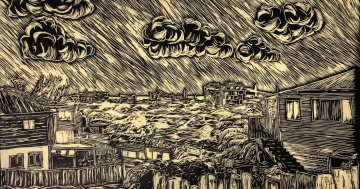

Early work on the Port Kembla Steelworks in April 1927. Excavations for the furnace foundations are to the right, with the stoves and raw materials bins in the centre. The gantry incline is under construction at left, with Five Islands Rd in the background. Photo: From the collections of Wollongong City Libraries and the Illawarra Historical Society – P06901.

Port Kembla Steelworks marked its 95th anniversary this week (29 August), just weeks after BlueScope announced the most expensive infrastructure project in the company’s history, the reline and upgrade of the No 6 blast furnace. Charles Hoskins had big plans when he moved his Lithgow steelworks to Port Kembla in the 1920s, but he never could have imagined how his vision would look today. We take a look back at those early days.

Before Charles Hoskins signed the deal to move his steelworks from Lithgow to Wollongong in the 1920s, another Australian industrial player had been eyeing off Port Kembla as a home base.

The Broken Hill Proprietary Company, better known as BHP, looked into basing its steelworks at Port Kembla, but found the issue of water supply too difficult to overcome.

That problem, combined with the government of the day offering BHP greater inducements to set up shop in Newcastle in 1915, led the company to abandon it as an option, opening the door for the Hoskins family to start the Port Kembla Steelworks.

Charles Hoskins was born in London in 1851. A couple of years later his family moved to Melbourne, where he went to school.

As a young man, Charles was a mail boy, tried his luck on the goldfields and worked as an assistant in an ironmongery store.

In 1876, he joined his brother George in Sydney in a small engineering workshop in Ultimo, which became G & C Hoskins Ltd in 1903.

The brothers built up the business, moving to larger premises in 1889 to establish a foundry, pipeworks and boiler shop and opening a Melbourne branch in the 1890s to make steel pipes.

According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Charles was no friend of trade unions, firmly believing in freedom of contract and opposing a minimum wage. He was a leader in the Iron Trades Employers’ Association of NSW and was prominent in the foundation of the Employers’ Federation of NSW in 1903.

G and C Hoskins took over the Lithgow steelworks in 1907 after the former owner ran into financial trouble. The purchase included a blast furnace, iron and steel works, a colliery, iron leaseholds, stocks of raw materials and a seven-year government contract.

George focused on the Sydney business while Charles moved his family to Lithgow in 1908 and undertook the development of the iron and steel industry.

The same year, Charles’s second son Cecil, who was educated at King’s College and Newington College, joined the family firm. Cecil became a director in 1912.

Inspecting plans for the steelworks in 1922 are (from left) Dr N Kirkwood, Charles Hoskins, N A Lang, M O’Donnell, William Davies MLA, Cecil Hoskins, and S R Musgrave. At the centre in a white coat is J B Ball, the Minister for Works. Photo: From the collections of Wollongong City Libraries and the Illawarra Historical Society – P05474.

But it wasn’t easy going for the Hoskins outfit. The plant was badly located, technological difficulties raised costs, facilities for manufacturing steel rails and structured steel were lacking and there were other bottlenecks.

Charles ran into trouble with the workers almost immediately when he tried to change from contract to day labour wages and the plant was closed when the men went on strike.

The Industrial Court declared the company was guilty of deliberately engineering a lockout and imposed a £50 fine.

In 1911, hostility increased when Charles dismissed a miners’ union delegate and inflamed the ensuing strike by importing blackleg labour from Sydney. The strike dragged on for nine months.

Despite increasing competition from BHP’s Newcastle steelworks, Charles’s Lithgow works flourished during World War I when he was called upon to manufacture many special steels that could no longer be imported.

In 1919, Charles bought out his brother George and the following year the company name was changed to Hoskins Iron and Steel Co. Ltd.

Charles retired as managing director in 1924, but not before he had decided that Port Kembla would be the company’s new headquarters.

In December 1920, under the simple heading “GOOD NEWS”, the Illawarra Mercury reported that Hoskins Iron and Steel had signed a deal to buy 380 acres [153 ha] of the Wentworth Estate at Port Kembla.

“It is the intention of the Company to proceed with the construction of works on the site where the manufacture of iron and steel will be carried out on a large scale, similar to the operations now carried on at Newcastle by the Broken Hill Proprietary Coy., Ltd,” the story declared.

“Mr Hoskins has for a long time been impressed with the possibilities of the district, but many difficulties stood in the way of carrying out his objective, but Mr Hoskins is not the type of man to be deterred by obstacles, and he has gradually overcome all the difficulties until today the achievement of his desire for the establishment of big works in the vicinity of Port Kembla have been overcome.

“Severe tests have been made by independent experts in regard to the suitability of the Port as a shipping centre for large works of the nature which it is proposed to establish, and in every instance satisfactory reports have been made. The same applies to the local coal, and other necessary products.”

Cecil became chairman in 1925 and, with his brother Arthur, joint managing director of the family enterprises.

Sadly, Charles died before he could see the realisation of his vision.

Following his death in February 1926, the Mercury wrote: “He had been associated with the Illawarra district for some years, first in regard to the Wongawilli mine, and latterly in connection with the big scheme to establish iron and steel works at Port Kembla. He had a wonderful faith in the possibilities of the district, and predicted that very big developments would take place within the next ten years.”

It was left to Charles’s wife, Emily, to apply the torch to light the first blast furnace of Australian Iron and Steel Ltd at Port Kembla on 29 August, 1928.

In the descriptive news style typical of the day, the Mercury reported: “There was no fanfare of trumpets or other sensational demonstration to mark this historic advance in the industrial life of Australia and the ceremony was of the most practical character.

“Some half dozen cars, containing a few representatives of Hoskins Ltd had arrived in the morning and after lunch, the latter made their way across the intervening space, alive with men at work, from the headquarters to the furnace and forthwith the blaze commenced which is to usher in a new era in the production of pig iron and its kindred activities in the realm of steel.

“Then the seething smoke fumes created an atmosphere which caused most of the spectators to vanish down the iron stairway, leaving those intimately responsible to watch the progress of the fire, and feed the rapacious maw of the furnace, which will go on now, without ceasing, day and night.

“The furnace is the largest and best equipped in the British Empire, and is the first unit of the new Port Kembla works to go into operation.

“Wherever possible, Australian made material and equipment have been used in the construction of the plant, which has been built under Australian supervision by Australian workmen.”

Emily died only a few months later, leaving her sons Cecil and Arthur at the helm. A new company was formed in 1928 to finance the operations, and its name became synonymous with the Illawarra – Australian Iron and Steel (AIS).

In 1935, the Hoskins’ company link to Port Kembla ended when AIS became a subsidiary of BHP – returning the Big Australian to the place that was its first choice for steel making in NSW, the Illawarra.