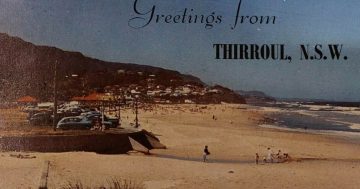

Photo taken on Thirroul Beach in June 1922 by Alfred Calcott, who ran a small real estate office from Harbord Street Thirroul. His agency (basically run by his wife Lucy) rented the house Wyewurk to David Herbert and Frieda Lawrence on 28 May 1922. Photo: Courtesy Enid Gorton.

Long ago a passage from the novel Kangaroo struck me as pure fiction: “In the afternoon they all went strolling … they walked across two fields to have a look at an aeroplane which had come down with a broken propeller.” (Chapter five.)

On checking the local papers, however, they confirmed Lawrence wasn’t just on drugs and imagining stuff:

“On Sunday afternoon last an aeroplane piloted by Mr T H [Thomas Henry] Barkell, a war aviator, landed on Thirroul Beach, and has since done big business by giving local residents a bird’s eye view of Thirroul. Mr J Ible, the local milk vendor, speaks in glowing terms of his flight along the coast; Mr E[ric] Bergman (jeweller) and wife [Susan Bergman] have had several spins, and have been able to take some fine photos of Thirroul from the air.”

How I longed to see those aerial photos – but, instead, while interviewing a Thirroul resident I was shown some other old photos of Thirroul.

With my vast knowledge of early aviation (which could be written on the back of a postage stamp in very large letters) I could instantly recognise Mr Barkell’s Thirroul plane as looking a bit like the kind of aircraft he was flying back in Europe – the Sopwith 7 F.1 Snipe – which, as everyone in Lawrence Hargrave’s Stanwell Park knows, was originally a single-seat biplane fighter of the Royal Air Force.

Interesting, I guess. But when I turned over the back of the photo things got curiouser and curiouser.

Staring closely at the small format image I could see the headland at the southern end of Thirroul Beach (in front of today’s “Pumphouse”) and the houses dimly seen upon the headland are the Seacliff guesthouse and Chirrup (further up Cliff Parade).

Thirroul real estate agent Alfred Calcott reported he “went up in this aeroplane on the 24th June 1922″. Photo: Supplied.

Kangaroo, written by D H Lawrence in Thirroul in the winter of 1922, describes people taking joy flights in an aeroplane that was taking off and landing on Thirroul Beach.

“The old aeroplane that had lain broken-down in a field was nowadays always staggering in the low air just above the surf … and lurching down onto the sands of the town beach,” Lawrence wrote.

“There, in the cold wind, a forlorn group of men and boys round the aeroplane, the sea washing near, the marsh of the creek desolate behind.

“Then a passenger mounted, and men shoving the great insect of a thing along the sand to get it started. It buzzed venomously into the air, looking very unsafe and wanting to fall in the sea.

“Yes, he’s carrying passengers. Oh, quite a fair trade. Thirty-five shillings a time. Yes, it seems a lot, but he has to make his money while he can. No, I’ve not been up myself, but my boy has. No, you see, there was four boys, and they had a sweepstake: eight-and-six apiece, and my boy won. He’s just 11. Yes, he liked it. But they was only up about four minutes: I timed them myself. Well, you know, it’s hardly worth it. But he gets plenty to go. I heard he made over 40 pound on Whit Monday, here on this beach.

“It seems to me, though, he favours some more than others. There’s some he flies round with for 10 minutes, and that last chap now, I’m sure he wasn’t up a second more than three minutes. No, not quite fair … he was a flying man all through the war. Now he’s got this machine of his own, he’s quite right to make something for himself if he can.

“No, I don’t know that he has any licence or anything. But a chap like that, who went through the war – why, who’s going to interfere with his doing the best for himself?” (Chapter 10.)

The Thirroulians who paid to go up in Barkell’s plane were brave indeed because just days before the local press reported that “Lieut Barkell, aviator, narrowly escaped crashing with a passenger at Bulli”.

The main reason Lawrence was in Thirroul was he was broke, and rents, unlike today, were cheap in winter. And so not being able to afford a Thirroul joy ride may well have saved Lawrence’s life and given him the eight more years needed to come up with his best-known novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover.