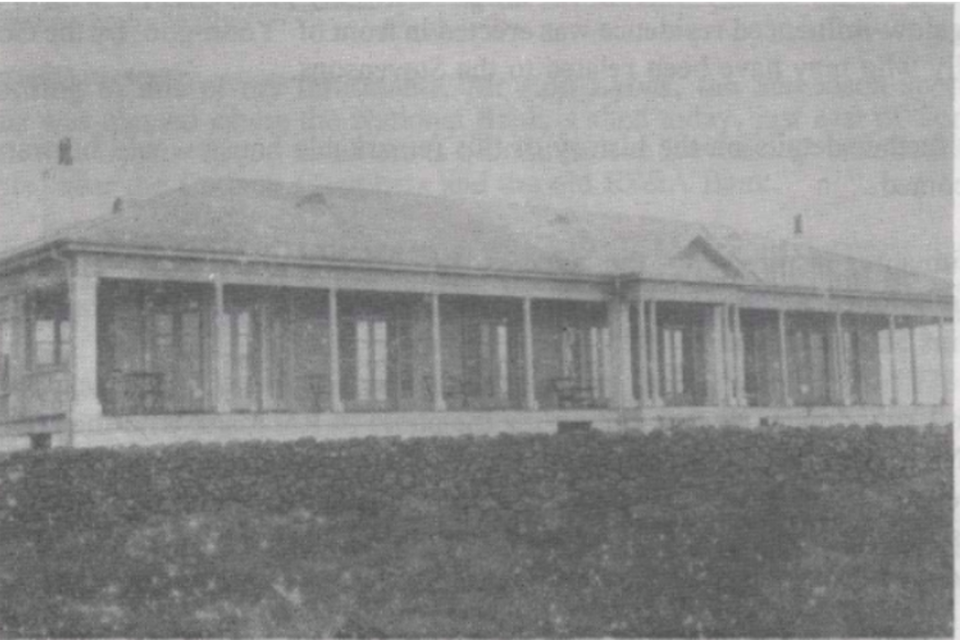

Yoon-Goo was built in 1913 at the top of a hill in Kiama. It was demolished for home units in the 1970s. It also had a Thomas Newing drystone wall (seen here covered in what looks like ivy) out the front. Photo: Supplied.

A very old Illawarra joke is that Wollongong is actually an Indigenous word meaning “place of very bad architecture”.

But when Australia’s foremost domestic architect of his generation, William Hardy Wilson (1881-1955), undertook the greatest walk in Australia’s architectural history along the Cow Pasture Road, the furthest south he got was the Illawarra.

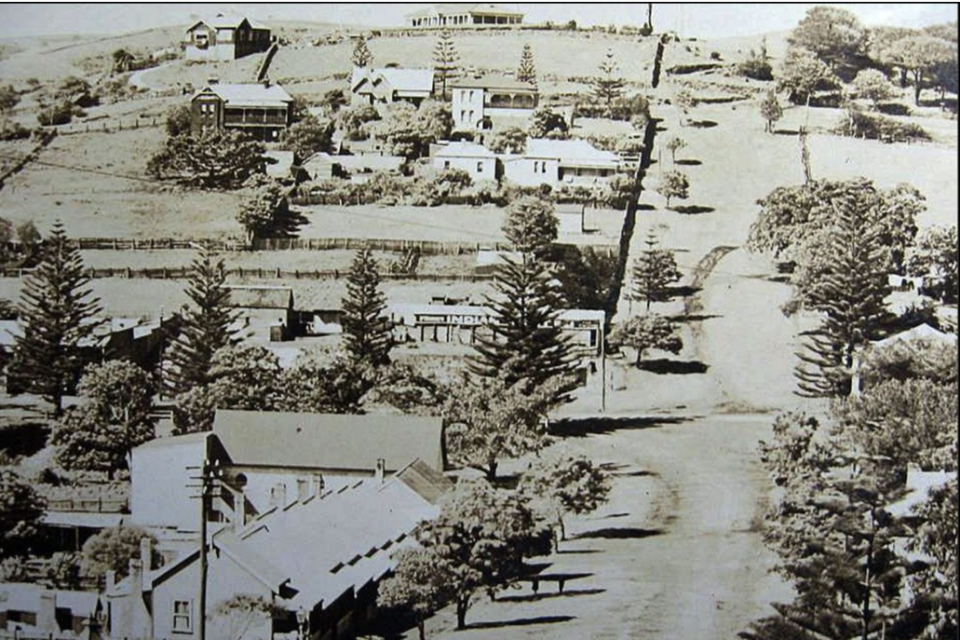

There, down near Market Square, Wilson found a remarkable residence and former business premises still standing in 1913 but which had definitely been in existence since at least 1851 and possibly for some years prior to that.

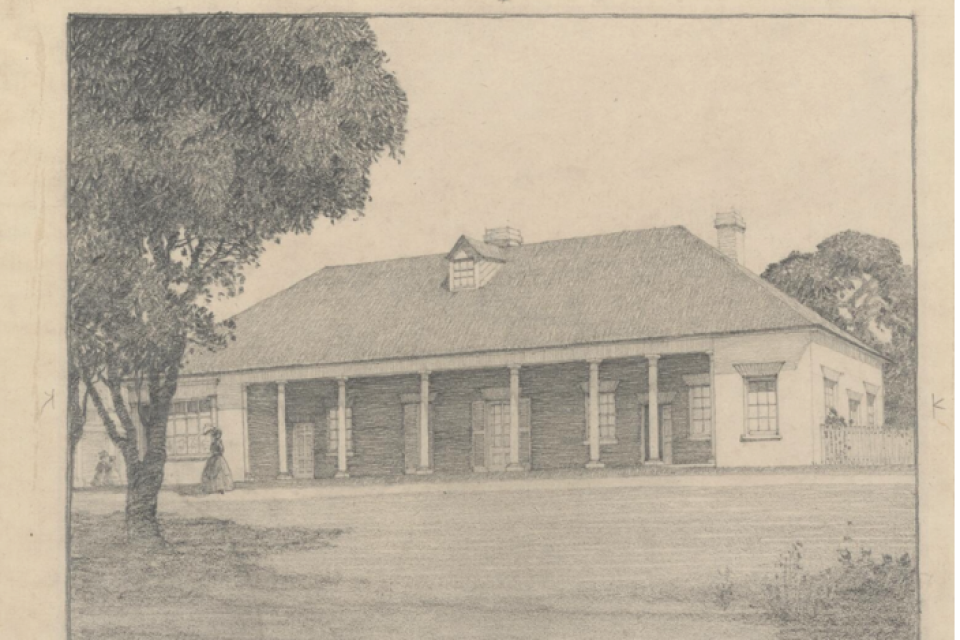

Even though this Wollongong building did not make the cut in Hardy Wilson’s magnificent giant 1924 folio Colonial Architecture in New South Wales and Tasmania (printed to the highest standards in Vienna), Wilson loved the old Wollongong building so much he could not resist drawing it with his usual meticulous care.

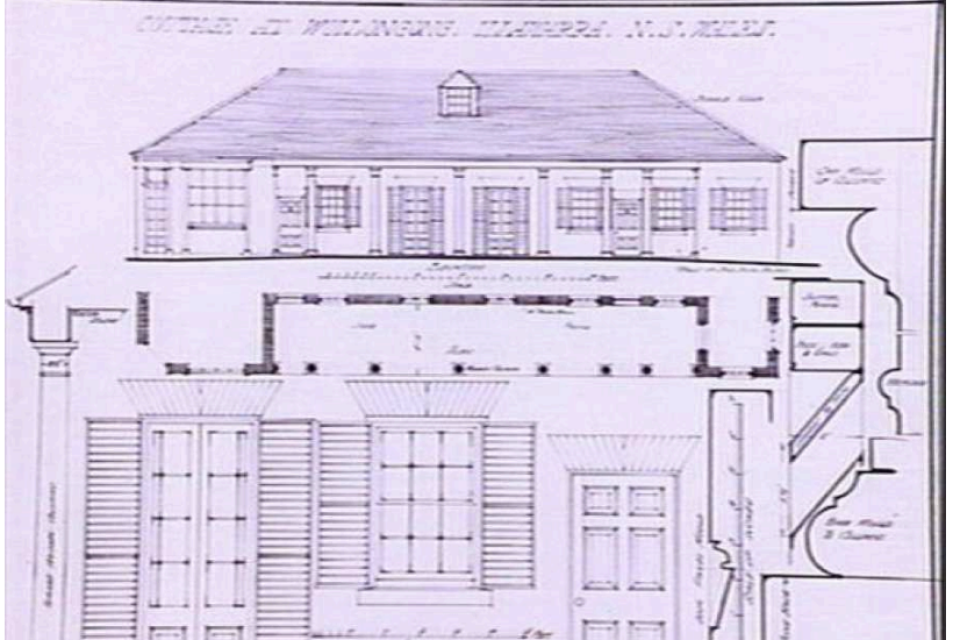

For Wilson was not just an architect but also a watercolour artist of very considerable skill. Not only did he draw the building lovingly but – as architects do – produced measured drawings as well.

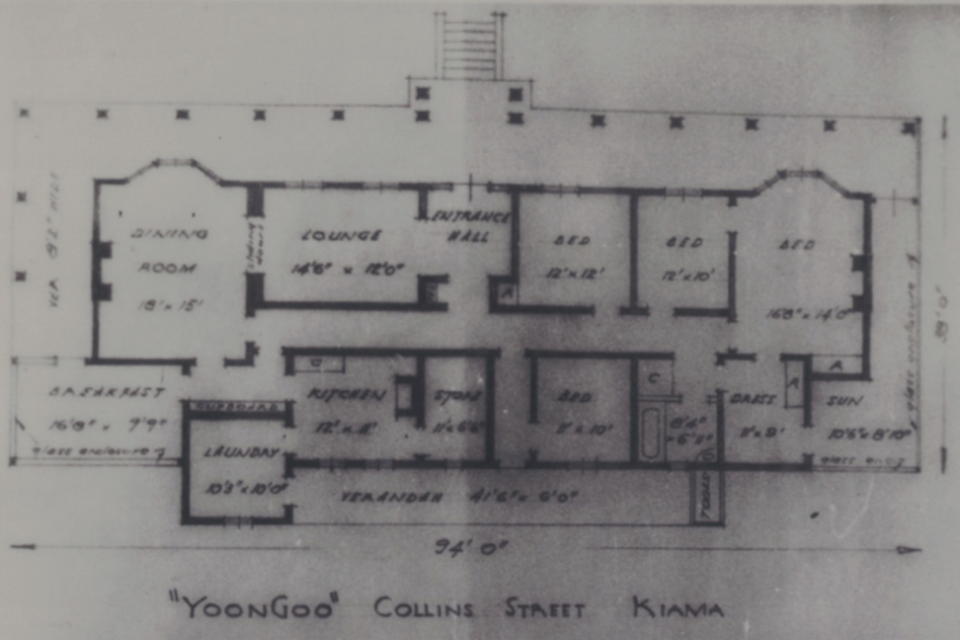

It would seem that Wilson’s close observations of a now lost Wollongong architectural treasure had quite a deal of impact on the extraordinary house he soon designed for RH Stevenson at Kiama.

Hardy Wilson was Australian born and from an extremely wealthy family. His mother, Jessie, descended from the pioneering Australian nurseryman Thomas Shepherd – hence Hardy Wilson’s interest in creating both houses and gardens in quintessential harmony.

Hardy Wilson’s headmaster at Newington had said to him: “Wilson, you are good at drawing. Become an architect” – and so he did.

Wilson then took articles (there were no Australian university courses in architecture back then) but also some lessons from the famed Australian artist Sydney Long and exhibited watercolours with the Royal Art Society of NSW in 1903.

But Wilson – instead of immediately becoming either an architect or a practising Australian artist of independent means – took a delayed “gap year” and travelled the world looking at art and architecture that lasted nearly a decade.

By the time Wilson returned to Australia he had made a close study of ancient European buildings and early American colonial architecture and determined to do the same in Australia – hence his walking and sketching tour of the colonial mansions that back then still lined the Cow Pasture Road in western Sydney.

For his famed book, Colonial Architecture in New South Wales and Tasmania, Hardy Wilson did not display mere sketches but the finest of carefully worked pencil drawings, most of which he spent at least 1000 hours producing.

There are really no more finely reproduced images in any book published by an Australian in the 1920s.

But, of course, few Australian artists or architects could then afford such high standards in a privately financed publication or possess the ability to produce such detailed work.

Despite this, after publication of the work and the original pencil images from it being eventually purchased by the Australian Government, Hardy Wilson basically gave up architecture and eventually moved to Flowerdale in northwestern Tasmania.

Wilson was rarely keen on clients. Indeed, he is reputed to have once said the only client he ever really liked was one who arrived with a door knocker and said “design me a house around this”.

As a part of the practice of Wilson, Neave & Berry, Wilson’s main role was often to do lunch and woo wealthy clients and it is likely that Neave and Berry were often left to do quite a bit of the legwork if the client was too demanding and Wilson was less than keen on the client’s demands and desires.

Kiama’s RH Stevenson obviously gave Wilson a very free hand and the demolition of the extraordinary Yoon-Goo in the 1970s may well be the Illawarra’s greatest domestic architectural loss.