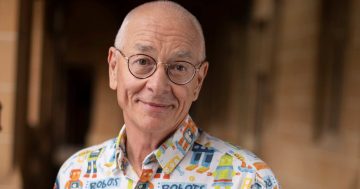

Distinguished Professor Sharon Robinson AM has been nationally acknowledged in the 2023 King’s Birthday Honours List. Photo: Jessica Bramley-Alves.

A casual conversation, a bold ‘FYI’ in a job interview and indelible curiosity led scientist Sharon Robinson to a distinguished career, a higher purpose and a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in the 2023 King’s Birthday Honours.

The UK-born biochemist had just delivered a talk at a conference on her photosynthesis research into why certain plant leaves produced red pigments when an attendee approached and asked if she’d ever been to Antarctica, where entire beds of moss turned bright red in summer.

“I was immediately fascinated,” she said.

“It was around that time that the hole in the ozone layer had been discovered and people were worried about the impacts of the increased UV on the Antarctic. I wondered if perhaps that was one of the causes – maybe these plants were creating red pigments as a kind of sunscreen.”

Though she was already applying for a job at the University of Wollongong (UOW), she submitted a grant proposal to pursue a study.

“In the interview, I told them ‘If I get the job and I get this grant, I’ll have to go to Antarctica at the end of the year for four months’. I don’t think they thought I would get it. But I did – the job and the grant,” she laughs.

“So as it turned out, in my first year at UoW I went down to Antarctica for the first time and it all began.”

That was in 1996. Today, she is a Distinguished Professor at the UOW and an internationally renowned scientist.

Prof Robinson’s immense contribution to the field of climate science has now been nationally acknowledged in the 2023 King’s Birthday Honours List.

Notably, for the first time since the Order of Australia was established in 1975, this year the majority of recipients in the General Division were women and there is gender parity or better at the three highest levels in the Order.

Though delighted to be part of this cohort, it was the presence of the award in the science sector Prof Robinson was most excited by.

“This is a public recognition of the importance of science to the community, and that is a great thing,” she said.

“This year has shown diversity in terms of who’s awarded and what we as a society think is important. For younger people thinking of getting into science, I hope this demonstrates that it’s something valued by the community as a whole.”

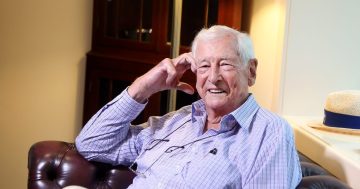

Prof Robinson said the world must act faster to stem the tide of climate change. Photo: Andrew Netherwood.

Prof Robinson spent her first Antarctic adventure at Australia’s Casey Station, which contains “the most moss beds in continental Antarctica”.

“Plants form the main part of the ecosystem down there, and I was deeply fascinated with their ability to cope with being frozen nine to 10 months of the year,” she said.

“They’re tiny plants but can be up to 500 years old. So they’re like these incredibly resilient, miniature old growth forests.

“Now they have climate change to contend with.”

Prof Robinson has since spent about a year in total in Antarctica including six months of the two years she was required to spend in Australia for citizenship eligibility. Luckily, it was in the Australian Antarctic region, and the Attorney General’s office made a special ruling to grant her nationality.

In all those months spent in one of the world’s most frigid, isolated and unforgiving environments, she said the scariest thing she has seen was actually taking place in developed nations the world over – a glacial response to the existential threat of climate change.

“For a long time we thought East Antarctica – the big bit – would stay quite cold and was quite protected from the major effects of climate change. But although the air temperature has remained cold, warming ocean water is eating away the ice underneath,” she said.

“This year the Antarctic sea ice is the lowest on record. That’s 60 metres of sea level locked up in that ice. It won’t melt immediately but once it begins, you can start processes that are unstoppable. The fact is, we’ve already committed to certain consequences … But the longer we take to act, the more devastating it’ll be.”

Prof Robinson is part of the large Antarctic grant program known as Securing Antarctica’s Environmental Future. It has gathered a consortium of learning and science institutions and museums looking at how their combined findings in physical sciences could be applied to protecting Antarctic biodiversity and, ultimately, the planet.

“Climate affects Australia very strongly – we see it in the floods, the bushfires, the droughts. It’s all linked,” she said.

“By developing best practices in environmental stewardship for the Antarctic, we’re protecting the entire globe.”