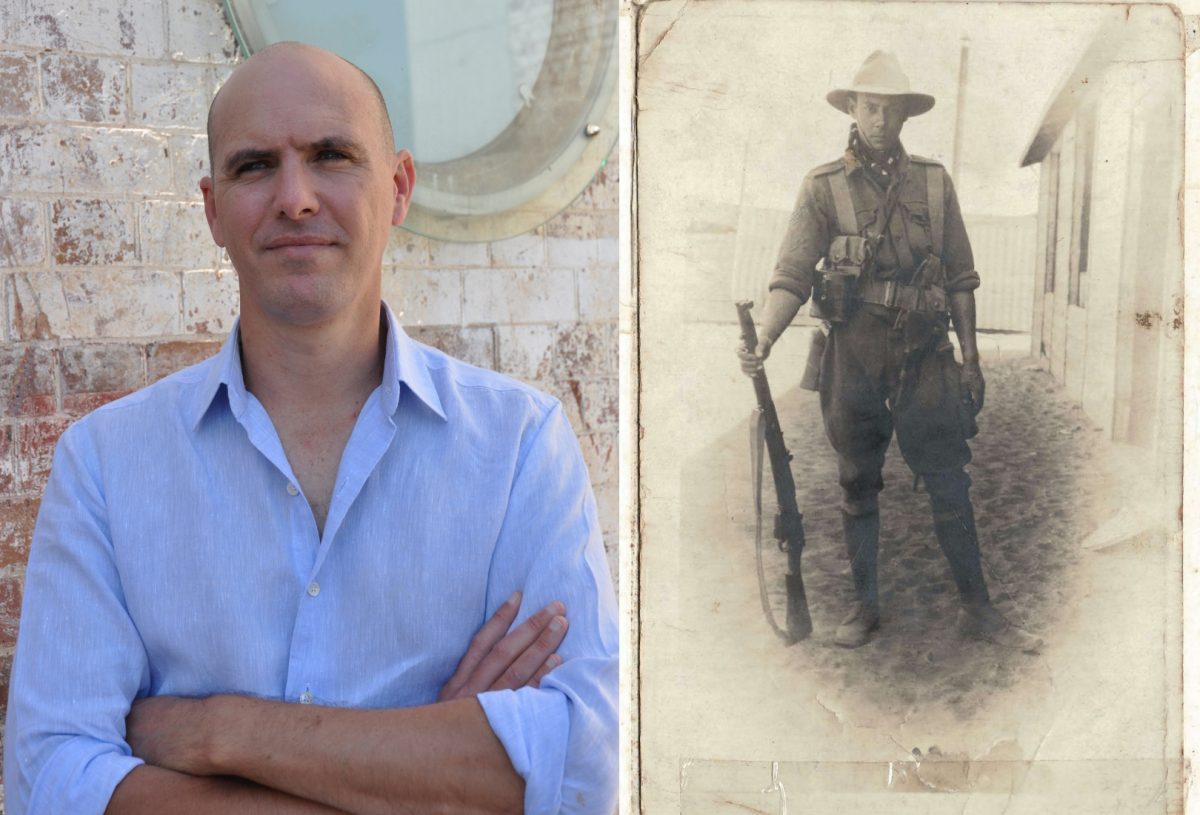

Author Ryan Butta (left) and Harry Freame in Egypt shortly before leaving for Gallipoli. Historic photo: Courtesy of Susan McGregor.

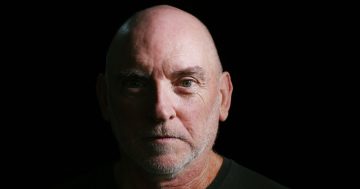

Kiama author Ryan Butta is bringing the extraordinary but little-known story of Gallipoli hero Harry Freame to life, sharing his journey from samurai upbringing to wartime bravery and espionage at two upcoming Illawarra events.

Through his book The Bravest Scout at Gallipoli, Ryan explores Harry’s untold contributions to Australia’s history — and his fight to have them properly recognised.

He said he first came across the story while researching foreign-born Australian soldiers.

“What struck me about his story was that you don’t hear of too many samurais at Gallipoli – that already is very intriguing,” he said.

“But what prompted it from being a bit of interesting research to I’d kind of like to write a book about this guy, was when I found out he was in an unmarked grave in Sydney.

“I just thought, how we interact with and how we hold up the Anzac legend, and then to think that someone who won the first Distinguished Conduct Medal was actually in an unmarked grave.”

As he read more, he discovered the Japanese-born Australian soldier’s story was surrounded in mystery, with the cover-up of his death.

“I thought, OK, this could be a really interesting story to tell, and one that people might like to hear about, because it’s an Anzac story, but it’s also a story of Australia and the White Australia policy and of Japanese Australian relations in the early 1900s,” he said.

Ryan said Harry led “an amazing life”, being raised as a samurai, risking his life to scout the beaches and hills at Gallipoli, becoming one of the first soldier settlers, becoming a champion apple grower and being recruited into Australian intelligence to spy on the Japanese community in Sydney.

But it doesn’t end there.

Before Japan’s entry into World War II, Australia opened a diplomatic legation in Tokyo, and Harry was sent as a translator – but his real role was a spy.

Extraordinarily, his cover was leaked by the Australian press, and the Japanese secret police tried to assassinate him not long after his arrival in Tokyo in 1941.

Harry died in Australia a few weeks later, but his sacrifice was never acknowledged by Australia.

“That’s the strap line of the book, the many lives and tragic death, because he had a lot of different lives,” he said.

“You get into his story, and you start opening all these other doors into really interesting bits of Australian history.”

For Ryan, it was more than writing a book, but also petitioning the government to recognise Harry’s service, leading to him finally having a headstone.

“The thing is, you don’t get a war grave unless your death is connected to your service and they always said it wasn’t, and I was trying to prove that actually it was,” he said.

He said the government always maintained Harry died of a rare gallbladder cancer unrelated to his work, but through the book he wanted to show how the attack while on duty in the Second World War caused his death.

“We ended up with a bit of a drawn match because they said, ‘Oh, we’re able to connect his death to his service, but not through being attacked’,” he said.

“They said the cancer, which I don’t think he ever had, was connected to cigarettes he was given at Gallipoli.”

During author events in Wollongong on 26 February and Shellharbour on 24 April, Ryan will also discuss the process of uncovering Harry’s history and the importance of recognising the diverse contributions to Australia’s wartime legacy.

“I talk about why I think he deserves his place in history, and why he deserves to be remembered,” he said.

Ryan said researching Harry’s story was “a bit of serendipity”, travelling to his soldier settlement at Kentucky near Armidale and visiting the War Memorial in Canberra, before finding a Ballina man who wrote about Harry and interviewed his daughter in the 90s.

“He told me that his daughter had all these letters from Harry’s time that Harry had written and people like [historian and Australian official war correspondent] Charles Bean had written to Harry.”

However, she passed away in 2019 and had no children, prompting Ryan to put in requests to find the executor of her estate.

“I didn’t think anything more of it,” he said.

“I’d just moved to Kiama and been here for maybe a month and I got a phone call from a lady. She said, ‘I think you’re looking for me. I’ve got Harry Freame’s possessions.'”

She was the best friend of Harry’s daughter and was given all his possessions when his daughter moved into aged care.

“I’m on the phone and thinking, I’ve just moved to Kiama and now I’m going to have to get on a plane and go somewhere else,” he said.

“I said, ‘Where do you live?’ and she said, ‘Robertson’.

“To think of all the places she could have been, and she was 30 minutes up the road.”

Ryan said Harry’s story still resonated today – despite his skills and bravery in both world wars, he was never accepted as an officer.

While he faced barriers at the top, he was deeply respected by the soldiers he fought alongside, who trusted his intelligence to guide their attacks.

“It’s funny, because … he was just a sergeant, and generals were writing to him. But in those letters in 1916, they say he was a leader of the men; the men loved him,” he said.

“The reason he wasn’t made an officer was because the higher up generals thought he was Mexican.”

Book tickets for Friends of Wollongong City Libraries literary lunch on 26 February from noon at the Wollongong City Council, and Author Talk event on 24 April from 6 pm at the Shellharbour City Library.