The hauntingly beautiful Australia War Memorial at Villers-Bretenneux. Photo: Jen White. Inset: Private Ernest Mannell as a naval reservist. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

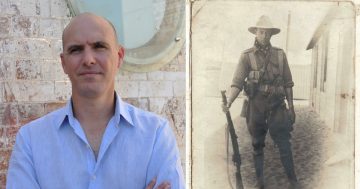

Ernest John Mannell, also known as Jack, was a 21-year-old labourer when he left Australia in 1915, headed for the front lines of World War I.

Sadly, at age 22 years and eight months, he was reported missing in action on the battlefields of France and it wasn’t until some months later that his death was confirmed.

His body was never recovered.

As Anzac Day approaches, I can’t help but think about that young man, far, far away from his family in Lakemba.

That young man, with the world ahead of him until it was stopped by an enemy bullet, was my great-great-uncle.

I wouldn’t have even known about Ernest were it not for my late grandfather, who was an avid historian even before family history became trendy.

With time and the benefit of technology, we have discovered that attention to detail wasn’t always Gramps’ strong suit.

However, he painstakingly researched the family tree and left us with a treasure trove of photos, memorabilia and paperwork that any genealogist would envy.

He didn’t have the luxury of the internet, of Google, or Facebook. He did his research the old-fashioned, foot-slogging way of the 1980s and 1990s.

He paid for documents that are now freely available and copied massive amounts of pictures and documents which he compiled into huge photo albums, complete with meticulous (albeit often incorrect) notes and cross-references.

It’s thanks to Gramps that I have this slightly battered photo of Ernest. Not only that but, stuck in the pages of these well-worn albums, I actually have his service medal.

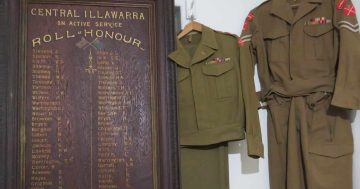

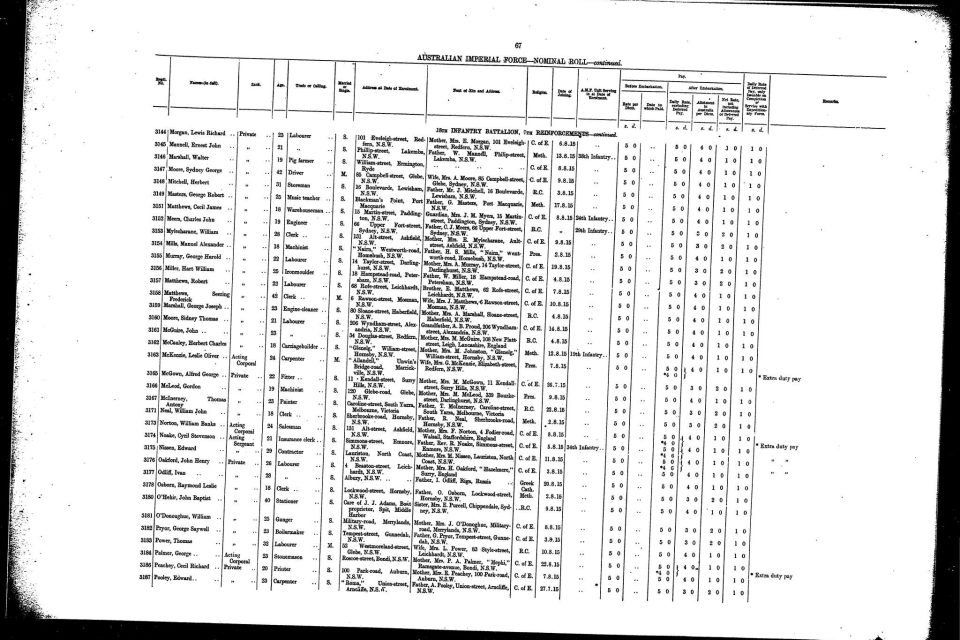

The inscription (according to Gramps’ notes) reads: The Great War for Civilisation, along with E J Mannell’s service number 3145 and his battalion, the 3rd AIF.

If Gramps were alive today, he would be amazed to learn how much information he could gather online about Ernest’s war service, thanks to the meticulous (and very accurate) work of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia.

Both are invaluable sites to anyone wanting to learn about their ancestors’ war records and I highly recommend both.

But what those official records do not and cannot capture are the family stories, the personal details that transcend the military service.

Gramps noted that “Ernie” was a very quiet lad. As any good genealogist should do he also noted the source – (authority, my mother).

In his cramped handwriting, Gramps recorded: “Ernest John Mannell, born 18 November 1834, the sixth child and second son to William Pierce and Matilda Mannell. Matilda was six months pregnant with Ernest when her fifth child died of dyptheria (sic) at the age of 2y4m. Ernest was only 3 yrs old when his mother died. Three weeks later he lost a sister aged 11 weeks.

“In 1912 age 18 he joined the Australian Naval Reserve. He served in the expedition to remove New Guinea from German control. Pining for positive action, he resigned from the Navy and joined the AIF on 21 August 1915.”

In my high school modern history classes I learned all about Archduke Franz Ferdinand and how his assassination in 1914 effectively started World War I. I can’t remember learning too much about the Australian involvement in the war and at that time I didn’t know about Ernest’s service record, nor Gramps’ historical records – all I knew was that I was related to someone who had fought in World War I.

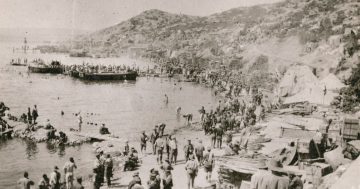

But it was a visit to the French village of Villers-Bretenneux and the battlefields around there that really brought it home in an unexpectedly emotional and heartbreaking manner.

We walked through trenches that had separated the Allies from the enemy a mere 500 m away and could only imagine the torrid conditions under which our soldiers lived and died.

In Pozieres, 23,000 men were killed in the space of five weeks, trying to claim a stretch of land which today takes about 10 minutes to traverse.

The Australian War Memorial just outside Villers is hauntingly beautiful. Row upon row of headstones entwined with bright red poppies stand testament to the sacrifice of Australian soldiers, many paying tribute to the “unknown soldier”.

It was here that the sacrifice of men like my uncle Ernest became all too clear. In a well-thumbed copy of the memorial register, was the entry: MANNELL, Private, ERNEST JOHN. The register details the names of the Australians who died protecting the French from the Germans. The register is the only physical reminder of the men whose graves are unknown.

On the morning of 28 February 1917, Private Ernest Mannell went missing.

He and a fellow battalion “runner”, Private Dignam, had been sent from the support line with a message to the battalion. The platoon was to relieve the front line and was waiting for the pair to return before “shifting up”. They never returned.

Initially it was believed Ernest was a prisoner of war held by the Germans, as Pte Dignam was.

Almost a year after Ernest was last seen, Pte Dignam replied to a letter inquiring about his mate’s whereabouts.

“Pte Mannell was killed in the morning of 28th Feb, 1917, just outside a village called Lebark. We got in between the German line and one of their patrols, we made a dash to get through and Mannell was shot through the head & killed outright. I am quite sure he was dead because I stayed about an hour with him before I was found and taken prisoner. This is the first time I have written to the Red Cross about him,” Pte Dignam’s letter read.

According to Ernest’s service record in the National Archives of Australia, it wasn’t until July 1917 that it was confirmed that he had indeed been killed in action.

We may not have a grave to visit, but thanks to amateur historians like my grandfather and official records now openly available, we are privy to more details about Private Mannell’s death than his immediate family was back in 1917.

And while today World War I may not be considered “The Great War for Civilisation”, we should never forget the men and women who did believe their service – and sadly their sacrifice – would save civilisation as they knew it.

Thank you Uncle Ernie. Lest we forget.