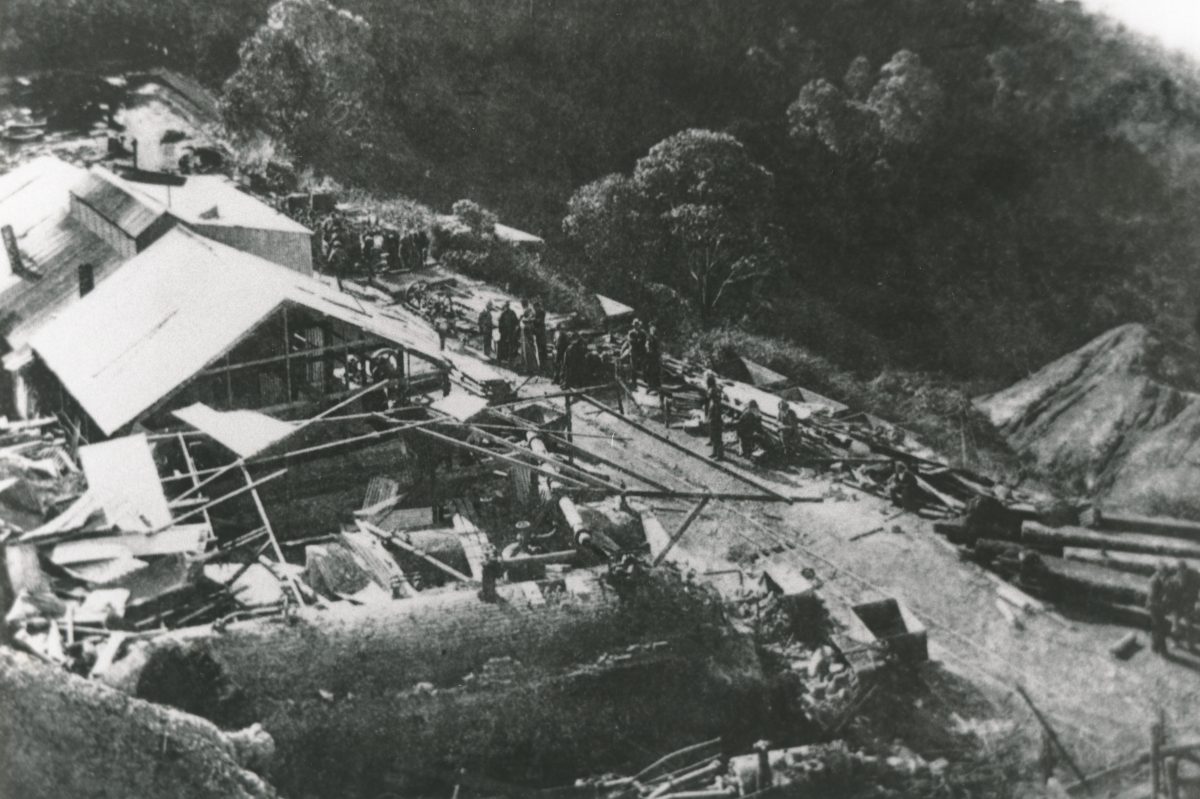

Ruins of the Mt Kembla Mine’s engine shed close to the mouth of the main tunnel. From the collections of Wollongong City Libraries and the Illawarra Historical Society – P08218.

They left home in health and strength

No thought of death was near

They had no time to say farewell

To those they loved so dear

– Inscription on the headstone of Thomas Dunning, 46 and his son Joseph, 24, both killed in the Mt Kembla Mine disaster.

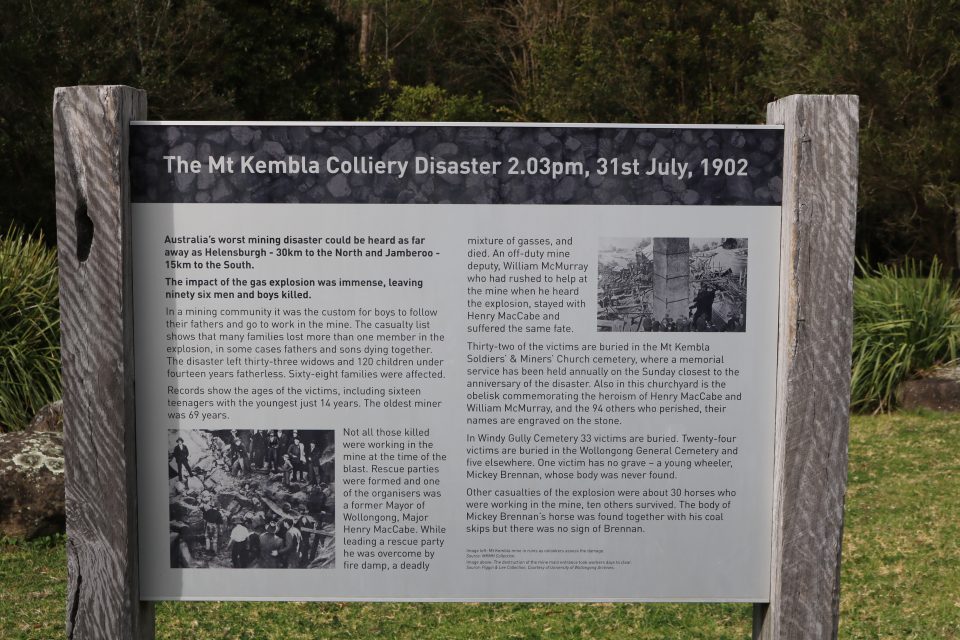

It was a quiet winter’s day on Thursday, 31 July, 1902 until just after 2 pm, when a massive gas explosion in the Mt Kembla Mine shook the Illawarra, felt from Helensburgh to Jamberoo.

According to accounts of the day, the cry went out across the village – “My God! The pit!” and people came from far and wide to the pit top. At the time of the explosion 261 miners were working underground.

The unthinkable had happened. The naked lamp of a miner had ignited gas that had gone undetected, seeping from the coal seam and collecting in a waste area of the mine.

A mine collapse had pushed the gas to where the miners were working. Men and boys as young as 14 were either dead or trapped inside the mine. The disaster remains Australia’s worst mining accident, claiming the lives of 96 men and boys.

The Illawarra Mercury provided a comprehensive account of the accident on Saturday, 2 August.

“The townspeople of Wollongong were thrown into a state of great excitement. A terrific report was heard, the windows of the houses rattled, and for a moment the people stood aghast wondering what had happened.

“Many attributed the noise to an extra large blast at Port Kembla quarry, while others in the town state that they distinctly noticed smoke and debris being blown upwards from Mount Kembla.

“There was, however, an almost unanimous opinion that some dreadful disaster had occurred in one or other of the mines. All doubt was very shortly removed by a telephone message received at the Wollongong Post Office. It was a brief statement to the effect that a dreadful explosion had occurred in the mine, and it was feared all the men had been entombed.”

The mine site was a scene of utter devastation and destruction. Virtually every building and structure had been laid to waste. What were once offices, engine rooms and boiler houses were unrecognisable heaps of smouldering rubble. The main entrance to the mine was buried under tonnes of debris made up of earth, stone and iron.

As rescuers attempted to enter the mine they were struck by the debris and hot smoke that pushed them back out of the mine.

Others who made it inside, succumbed to the afterdamp, a toxic mix of gases left in a mine after an explosion.

This unseen killer made men feel weary and they would sit down to rest, only to die from the mixture of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and nitrogen, sometimes with the addition of hydrogen sulphide.

The Mercury account said: “Mothers, daughters, and sons rushed to the mouth of the tunnel, and their worst fears were realised when they saw the blanched faces of the workmen there.

“Worse still, volumes of smoke poured out of the mouth of the tunnel and gave the idea that it would be impossible for the miners to survive such an overpowering blast.

“The screams of the women and children were heartrending. They felt certain, seeing the fearful outpouring of smoke and the ominous silence of the telephone which runs about two miles into the mine, that the explosion had smashed the wires, and possibly had caused the roof of the tunnel to collapse, thus making the men prisoners, and perhaps killing many of them.”

There were not enough safety lamps or stretchers for the rescuers to use and delays cost lives.

Some men made their own way out, with one group of 70 crawling through narrow passages in total darkness.

Others reported stumbling over the bodies of their deceased friends and relatives in the dark and confined conditions trying to find their way to clear ventilation.

The Mercury said willing hands from other mines made their way to Mt Kembla, while “civilians who were not miners cordially joined in the work”.

“Amongst those who assisted was Major (Henry) MacCabe, formerly manager of the Mount Keira mine. He took a prominent part in the rescue work at the Bulli disaster, and was again to the front with his advice and assistance.”

Major MacCabe was charged with coordinating the rescue effort. He also had to contend with the hundreds of volunteer rescuers who had converged on the mine. Sadly, he was one of only two men not at the mine at the time of the explosion to lose his life because of it. The other was nightshift deputy William McMurray, both men dying after being overpowered by toxic fumes.

According to Wollongong Heritage and Stories, Mary Dungey was at her Mt Kembla home when the blast threw her across the kitchen floor. Mary’s husband, Frank, was at work as the newly appointed mine safety deputy.

Frank suffered horrific injuries in the disaster, so bad that Mary fainted after identifying his decapitated body. She’d lost her soulmate and their seven children had lost their father; four of them were under 14 years of age.

After losing her beloved husband in the disaster of 1902, Mary waved two of her remaining sons off to war in WW1. In 1916 the news came that William had died at war followed by Jack in 1918.

Despite this grief and loss of children and her husband, Mary was a strong woman and lived the rest of her life in Mt Kembla. She died in May 1942 and is buried with her husband in the graveyard at the Soldiers’ & Miners’ Memorial Church, Mt Kembla.

Aside from being friends and workmates, the deceased were brothers, uncles and nephews, fathers and sons, cousins, grandfathers. Whole families were affected by the tragedy; 167 were saved, 96 were lost, one was never recovered.

By the time the bodies had been recovered, 33 widows and 120 children under 14 were left behind.

A royal commission into the disaster was held in 1903. It confirmed an earlier coroner’s jury finding that the incident happened when a large section of the unsupported roof in a goaf collapsed with considerable force, pushing air and methane gas into the main tunnel.

The rush of air and gas stirred up the coal dust clinging to the roof and walls of the mine. The coal dust made contact with an exposed flame light. The gas ignited and, combined with the now airborne coal dust, set off the initial explosion that blew down the main tunnel with such force that it destroyed everything in its path.

Rather than holding any individual official of the Mount Kembla Company responsible, the commission stated that only the substitution of safety lamps for flame lights could have saved the lives of the 96 victims. However, flame lights continued to be used well into the 1940s.

The annual 96 Candles Ceremony will be held at Windy Gully Cemetery, Mt Kembla tonight, Monday 31 July, at 6:30 pm. Buses will transport guests to and from the ceremony, from Mt Kembla Hotel and Kembla Heights Bowling Club between 5:30 pm and 6 pm (no parking is available at the cemetery).