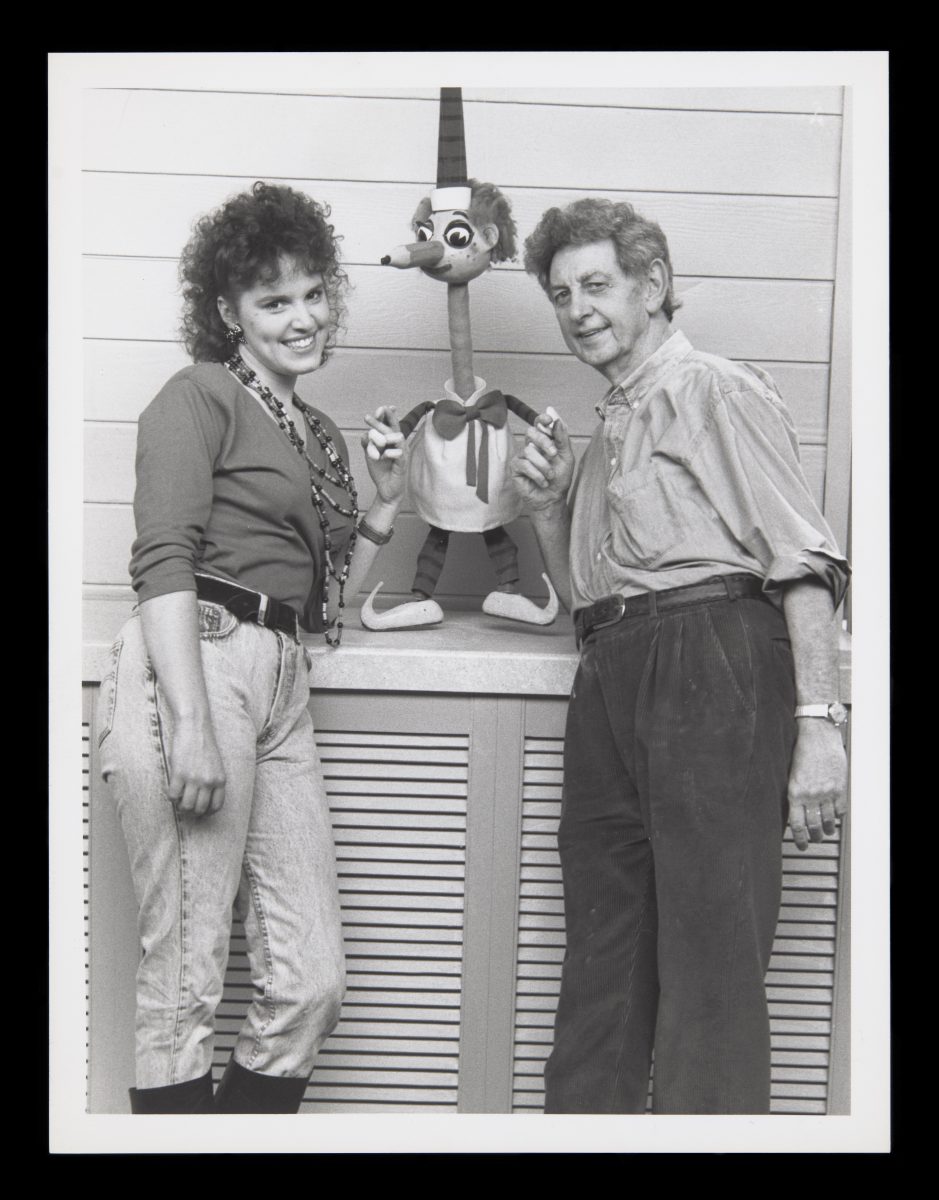

Rebecca Hetherington with Bill Steamshovel, Gus and Mr Squiggle. Photo: National Museum of Australia.

Soon after Chicken Run 2 landed on Netflix and news of an up-and-coming Wallace and Gromit film emerged late last year, rumours had it these would be the last productions to come from the Aardman Animations studio due to a clay shortage.

The UK-based company lost no time in putting these rumours to rest, saying there’s “absolutely no need to worry”.

“We have high levels of existing stocks of modelling clay to service current and future productions,” it said in a statement.

Here in Australia, there’s no such hurdle stopping Mr Squiggle from returning to TV screens. Quite the opposite, a former presenter reckons.

This iconic marionette and more than 800 related objects (including fellow puppets, artworks, scripts, costumes, props, sets, production notes, merchandise and audio-visual material) have joined the collection at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

Between the years of 1959 and 1999, the colourful, pencil-nosed character was hard at work in nearly every Australian’s living room, as the star of the ABC kids’ show Mr Squiggle and Friends.

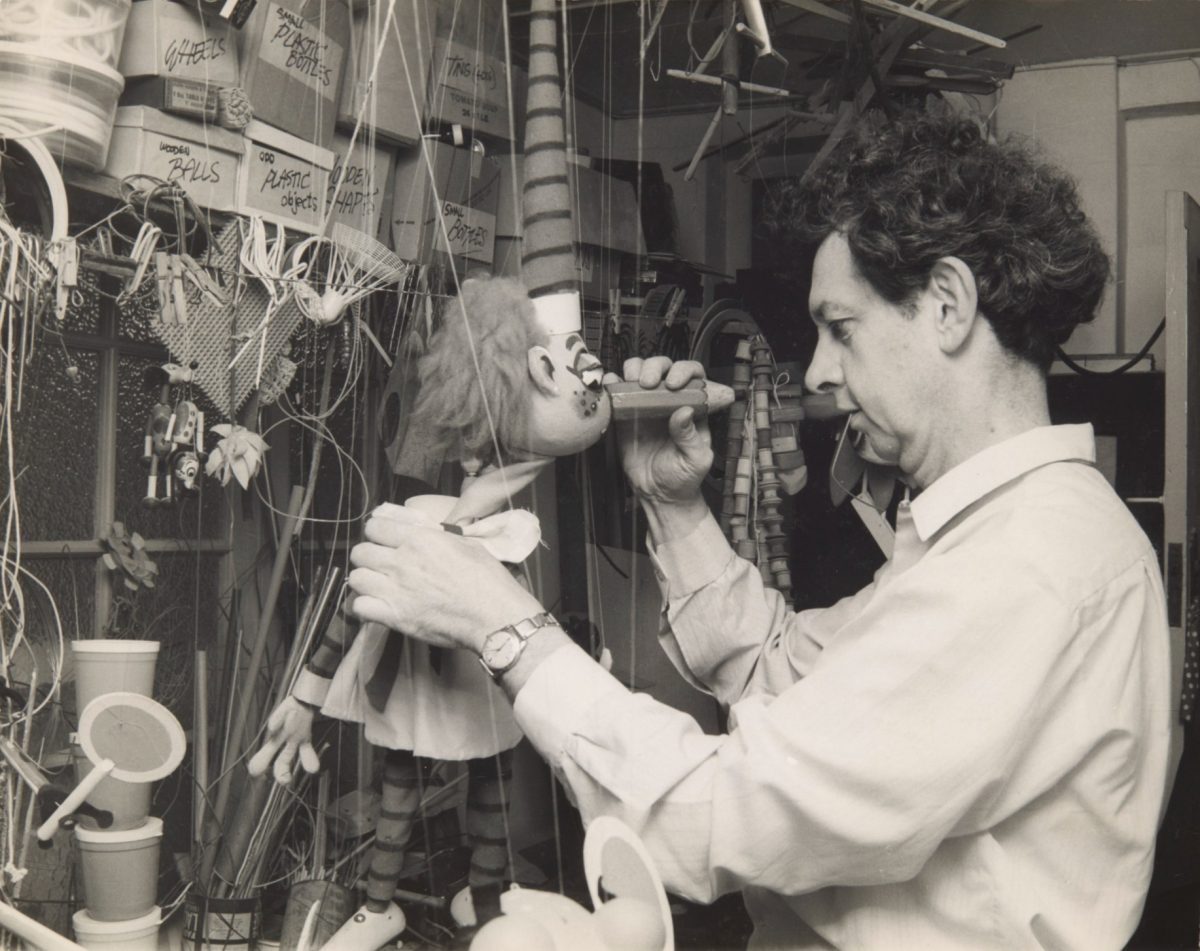

Norman Hetherington made all the puppets by hand. Photo: National Museum of Australia.

Children from across the country would send in their best drawings, and with the help of his puppet friends Blackboard, Rocket, Bill Steamshovel and Gus the Snail, Mr Squiggle would add his own touches live on-air.

This was at a time when computer-generated imagery (CGI) was in its infancy. The Star Wars trilogy was being made using complex models and artworks, Thunderbirds puppets were go, and Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends involved miniature models and dioramas.

Similarly, there was no digital cleverness involved with Mr Squiggle. Norman Hetherington was the man literally pulling the strings in the studio – often upside down – and later on his daughter, Rebecca Hetherington.

“Norman made everything himself in his studio, often from materials he found discarded,” National Museum curator Dr Sophie Jensen says.

“And he was constantly retouching and remaking and making sure every puppet, every character, looked their best at all times.”

Mr Squiggle’s backstory had him as “the man from the moon”, who would come down to earth for each week’s episode in his pet rocket. The smoke you saw puffing from Rocket’s thrusters wasn’t from a machine, it was talcum powder – and later (for WHS reasons), cornflour.

“We have on display here the suitcase Norman would take along to the ABC each time Mr Squiggle was being filmed, and inside he has his repair kit for if anything went wrong,” Dr Jensen explains.

“There are also two canisters in there that originally contained talcum powder before it went to cornflour, and this would be blown through pipes in the puppets to create the smoke for Mr Squiggle’s rocket and the steam for Bill Steamshovel.”

Norman never expected Mr Squiggle and Friends to last as long as it did. Over 40 years, the puppet and his master completed more than 10,000 squiggles, and as Dr Jensen says, “that is more than 10,000 children who had sent in their drawings”.

“We’re kind of used to seeing ourselves in social media now, but at the time Mr Squiggle was on, to see your name, to come up on the screen, and to see your artwork being interacted with – that was a pretty magic moment.”

Every school holidays, Rebecca would join her father in the studio to watch him at work (at least until she learnt The Aunty Jack Show was being recorded next door), and became his fellow presenter in 1989.

She says puppets, as well as other physical mediums like stop animation, have a “lovely tactile-ness” that’s been lost from modern shows “saturated” with CGI and cartoons.

“When my kids were little, there were certain shows that suddenly became cartoons instead of stop animation, but I see evidence of shows that are becoming puppet shows again,” she says.

“Puppetry and what it can do is experiencing a bit of a renaissance.”

Rebecca Hetherington and father Norman Hetherington with Mr Squiggle. Photo: National Museum of Australia.

When asked if Mr Squiggle would ever make a comeback to Australian TV, the answer was “never say never”.

“It’s something we as a family talk about,” Rebecca says.

“Obviously, he would be facing different questions and concerns in this day and age. He would still be gentle and kind and full of amazement and wonder – all those lovely qualities. If he did come back, it wouldn’t be from the moon, because that was the great unknown then, whereas now he’d have to come through a black hole or something.”

Original Article published by James Coleman on Riotact.