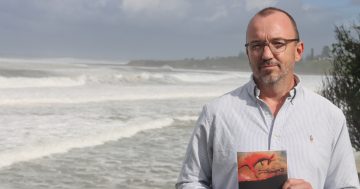

Holly Isemonger’s debut poetry collection, Greatest Hit has received rave reviews. Photo: Perrie Croshaw.

“Play is really, really important,” says Gerringong poet Holly Isemonger.

“Play can be profound and playing with words is poetry.”

Holly, former joint winner in 2016 of the Overland Judith Wright Poetry Prize, has just released her debut poetry collection, Greatest Hit. It has already received exciting reviews.

“The poems in Greatest Hit spool off the page like feisty, filmic reels,” says Keri Glastonbury, University of Newcastle’s Associate Professor in Creative Writing.

Keri says Holly’s writing is “irreverent, inventive and ingenious yet offset by the necessity of resilience”.

“These are poems of the South Coast surf, a regional psychogeography disrupting (often antipodean) cliches of teen cinema, soap operas and reality TV,” she says.

Holly says she puts her life into these works. At 32, she has already lived a surprisingly full life: primary school in Gerringong, high school in Kiama, a phase as a surf rat, time as a drummer in a band, much study (BA Comms and MA), travel abroad, a few years spent living on a peninsula in Scotland and Glasgow, then sadly some personal experience with addiction and mental health issues.

That’s why, while continuing to teach poetry, Holly is also studying to be an alcohol and drug counsellor and mental health worker.

But it’s the poetry that is her passion.

Holly likes to pull language apart then reassemble it. She wants to make poetry more accessible, especially for those who don’t naturally gravitate towards it.

She is happy to be experimental and irreverent, but never boring, and will never compromise style and form.

Australian academic and author Dr Chris Fleming says behind Holly’s often ingenious, formal experimentation is a sense of play and exploration which uncovers matters alternately grave and comic, sometimes at once.

“As good as these poems are,” he says, “there is more at stake in Isemonger’s work than a teasing out of the possibilities of language; these are poems about sense and nonsense, of falling apart and holding it together, of giving up and living on – in short, about what it means, or might mean, to be a human being.”

Holly says the poetry she studied at school, the solemn analysis, was often turgid and no fun at all.

“This kind of study can make people feel stupid and shuts down creativity. What you want in a good piece of writing is to stir the creativity in the reader, not to shut it down.

“Poetry should be a real joy. When we are little kids, we sing Ring Around the Rosie. When you sing it as a child you are not analysing it. Sometimes the sense doesn’t come from the words but from another place,” she says.

Both of Holly’s parents are teachers and she says she often writes for her mum.

“A part of me writes to my mum, who is a PE teacher. Poetry is not her natural territory. But she loves games and play. I think if I can get Mum interested in my writing, that would be great,” she says.

Her dad teaches at Shoalhaven Community College in Bomaderry and Holly has run some writing workshops there for him.

She says you don’t need to be “inspired” to write poetry.

“People trying to write often get stuck between old rules (rhyming, sonnet structures and so on) and ‘free verse’ where the lack of rules can be paralysing,” she says.

She uses different techniques to play her writing games.

“Drawing on the techniques of the Oulipo [a group of French writers and mathematicians from the 1960s who sought to create works using constrained writing techniques] and other formalist games, we can turn writing poetry into a productive game, into a real kind of play,” she says.

At present, she is using a “Google Translate” method of writing.

“I put text into Google Translate, pump it through lots of different languages, then translate it back into English, and it’s all distorted and strange. I had some of the people in my workshop do this with the first stanza of Banjo Patterson’s The Man From Snowy River. Stuff like this makes writing poetry less intimidating and fun,” she says.

Holly says writing poetry is not just about translating something you already know or feel, but discovering what you know or feel through the process of writing. She says this approach to writing poetry doesn’t mean the results generated are trivial or without beauty or power.

For Holly, playing with words creates her poetry.

Greatest Hit is available through Vagabond Press