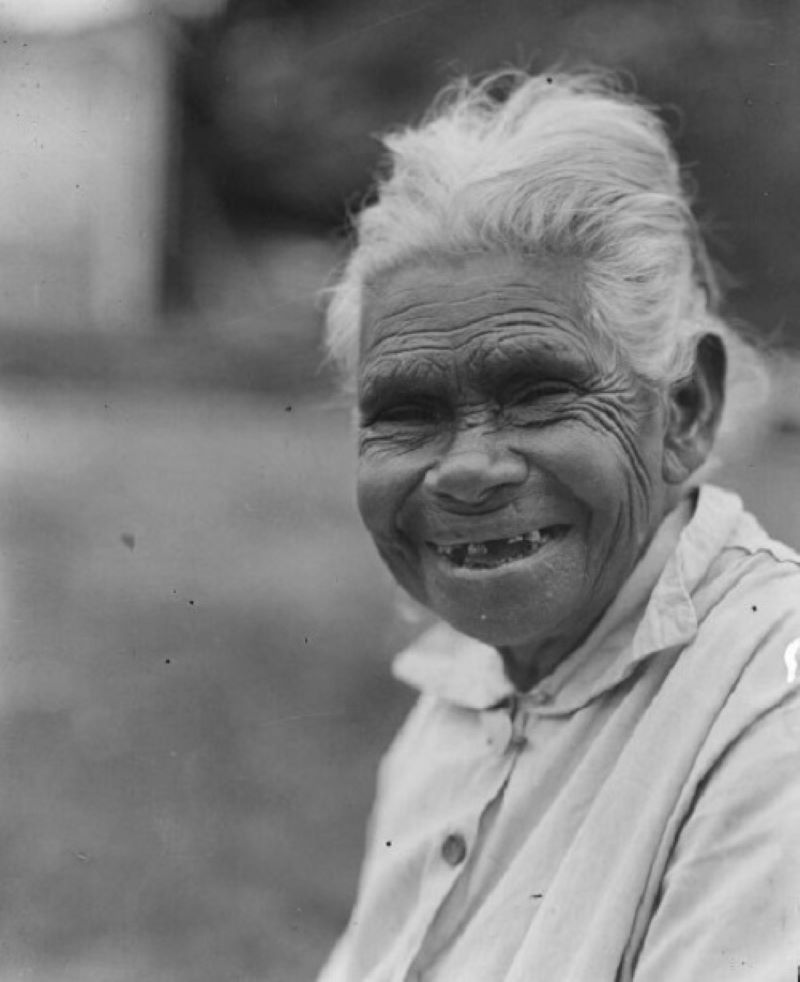

Even in her older years, Queen Rosie was often found singing and dancing to traditional music. Photo: Kiama Library.

Many are the tales and legends that old Queen Rosie can tell.

By the 1930s Rosie, born by the shores of Lake Illawarra – likely under the large birthing tree on what became called the Berkeley Estate – was said to be the oldest Indigenous person living in Illawarra and possibly close to 100 years old at the time of her death in 1934.

Her photo appeared in contemporary newspapers yet her old wrinkled face boasted a smile. Hair silvered with age, she nonetheless is said to have maintained much of her youthful vigour and even in advanced years Rosie could be found singing and dancing to the traditional music she knew as a child.

Queen Rosie became the wife of King Mickey Johnson – a man born far from Queen Rosie’s birthplace. That husband, according to the arch-conservative Major E H Weston of Dapto, was a youngster about 10 years old, called “Tiger”, whom Weston brought to Illawarra from the North Coast after, shockingly, being traded from an Indigenous man named “Tommy” for “a blue serge shirt”.

Transcribing Indigenous chants into European musical notation started early after 1788 but few would be aware that a version of one from Illawarra has actually been preserved.

That means that Rosie, having been born when Wollongong was only just being formally laid out as a town, was, nearly 100 years later, still capable of singing and dancing to rhythms and words that may well have pre-dated the colonial invasion of Illawarra.

Moreover, remarkably, a version of Queen Rosie’s music and dancing survived and was reproduced as part of a hit theatrical reproduction.

Australian pianist and composer Varney Monk (1892-1967) happened to one day be holidaying on the South Coast and in a tea shop in Kiama heard a tune being sung and danced by Queen Rosie.

Possessing a practised ear, Monk immediately scribbled down what she heard in an effort to notate both what Queen Rosie sang and some of the rhythms she danced, and then incorporated it as part of her hit musical Collits’ Inn (1932).

After playing for 15 weeks in Melbourne, the show had transferred to the Tivoli Theatre in Sydney by mid-1934 (the year Queen Rosie died) and ran for a further nine weeks. Moreover, following the Sydney run, the show returned to Melbourne, where it played a further four weeks at the Princess Theatre.

Queen Rosie became the wife of King Mickey Johnson. Photo: Kiama Library.

So surprisingly successful was Collits’ Inn that by 1936 the famous producer Frank Thring seriously considered that making a film of the production might be the go and so travelled to Hollywood to engage a director and actors.

Sadly, on returning to Australia, Thring was immediately hospitalised in Melbourne, where he died two weeks later. And, thus, no extant sound recording of Queen Rosie’s chant appears to survive as the radio recordings were also not preserved.

Nonetheless, in October 1943, ABC Radio, Sydney, produced Collits’ Inn with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, conducted by J Farnsworth Hall, in a production by Lawrence H Cecil.

Back in 1923, Queen Rosie was said to be “spending the eventide of her life in a snug little cabin” erected at a cost of £35 and to which a further £7 was donated by the schoolchildren of Kiama, Gerringong and Bombo to stock her cupboard, not forgetting to provide a plentiful supply of ”bacca of which she was fond and used to smoke using a clay pipe”.

After performing her songs, chants and dances, Queen Rosie would explain what they meant and how the rhythm might be obtained from natural sources such as running water from waterfalls or in hundreds of other ways.

Thus Queen Rosie’s chant “in praise of the moon and stars”, which Monk heard in that Kiama tea shop, went on to inspire the sound and choreography of the corroboree scene in Collits’ Inn.

And among the Monk papers held by the National Library of Australia are the words and music for her version of “Queen Rosie’s Aboriginal Chant”.

Queen Rosie’s longevity has enabled a version of the most unlikely thing for South Coast NSW history to preserve – something of what the sound of the Indigenous past may have been like before sound recording proved possible.

It would be wonderful if Wollongong’s most famous violinist, Richard Tognetti, could perform an arrangement of Varney Monk’s version of Queen’s Rosie’s contribution to the musical Collits’ Inn in one of the upcoming Australian Chamber Orchestra’s fine concerts at the Wollongong Town Hall.