The snowy albatross (Diomedea exulans). Not only does it have the greatest known wingspan of any living bird, but thanks to the work of some Illawarra individuals, we now know it’s also one of the most far-ranging birds. Photo: Supplied.

In the second half of the 20th century, Illawarra was blessed with a surprising number of intellectuals who had never been to university – people Antonio Gramsci termed “organic intellectuals of the working class”.

The Illawarra Natural History Society, which later became known as the Illawarra Conservation Society, had several.

But late in 2025, Illawarra lost one of its fine individuals – Lindsay Edward Smith (22 April 1951 – 28 November 2025).

Known to the cognoscenti as “The Albatross Man”, he was internationally recognised for the study and conservation of seabirds, especially albatrosses, along the Illawarra coast.

Trained as a fitter and turner, Lindsay Smith was later employed by the Australian Museum in 1987 as an ornithologist, working at the Elizabeth and Middleton Reefs in Australia’s Coral Sea Islands Territory.

In 1994, he became the founder, with Harry Battam, of the Southern Oceans Seabird Study Association.

As such, he became the inheritor of the long-term research work on albatrosses begun by the NSW Albatross Study Group in 1956 – the longest continuous seabird study in the world. And it was some older Illawarra working-class intellectuals who had made this possible. They were Alan Sefton, Doug Gibson and Arthur Mothersdill.

The only one of these I knew personally was Thirroul’s Alan Sefton (seen at left). He and Doug Gibson were cousins and if you enjoy bushwalking in the protected areas in the ‘Gong, then you will be aware of the Gibson Walking Track at Austinmer and the Alan Sefton Memorial Grove in Thomas Gibson Park at Thirroul.

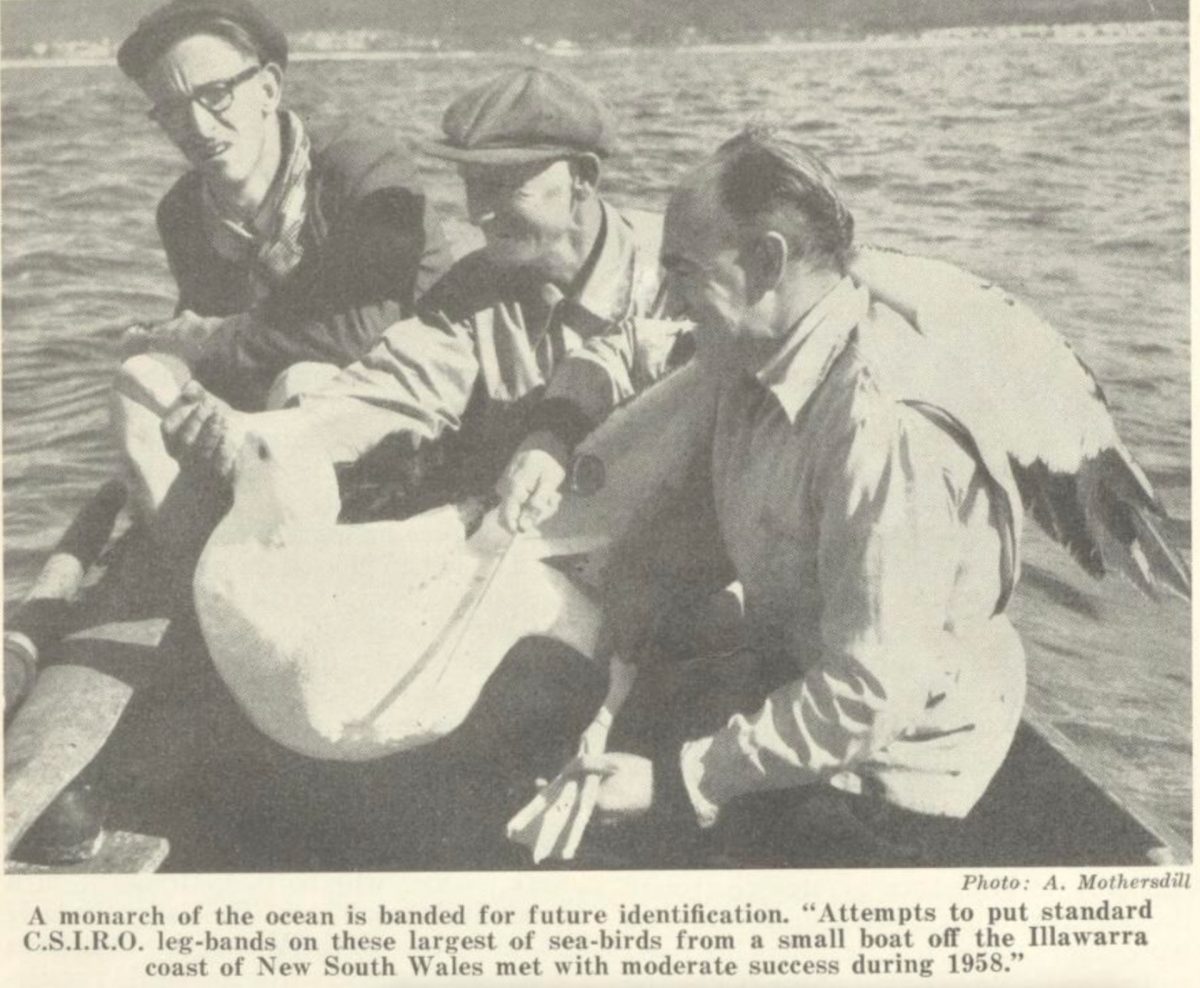

Walkabout magazine 1 November 1958. Image: Supplied.

Alan Sefton impressed others from a very early age. On the first day of his apprenticeship at the Port Kembla steelworks, “Mr Sid”, the boss, welcomed the new recruits and inquired if there were any questions. Young Sefton put up his hand and asked, “Why are you killing all the fish in Allan’s Creek?” Brave, but one would expect that he would soon be out the door well before his probationary period ended.

Yet Alan proved so capable that someone realised this man might be useful. The NSW Albatross Study Group (NSWASG) was an amateur ornithological fieldwork group that banded albatrosses and other seabirds off the coast of NSW. Primarily targeting winter feeding aggregations of wandering albatrosses, it developed its own catching methods.

Thus, the origins of the NSWASG lie in the pioneer albatross banding activities started by Doug Gibson and Alan Sefton in 1956 at Bellambi and by Bill Lane and Harry Battam in 1958 further north at Malabar. They understood that large concentrations of great albatrosses appeared in winter and raised the possibility among local amateur ornithologists of catching useful numbers at sea for banding.

Black-browed albatrosses also occurred in similar numbers, but wandering albatrosses were considered easier to catch and so the banding programs focused on them.

Initially, it was thought to involve only two great albatross species – the wandering and royal albatrosses. The group’s aim was “to accumulate … as much information as possible concerning Diomedea exulans (aka the wandering albatross, white-winged albatross, snowy albatross or goonie) when at sea”.

Almost immediately, the group was publishing serious research papers in publications such as Emu and Notornis and also in popular magazines such as Walkabout. The group revealed the great diversity among albatross species and one is now even named after Doug Gibson himself: “Gibson’s Albatross (Diomedea gibsoni)”.

The local method for characterising the seemingly infinite variation in appearance of great albatrosses has proved instrumental in the recognition that there are multiple populations and thus laid the groundwork for international field identification.

Gibson’s Albatross (Diomedea gibsoni) commemorates John Douglas Gibson, the Thirroul amateur ornithologist who studied albatrosses off the Illawarra coast for more than thirty years. This one is seen flying over the Tasman sea off McCauley’s Beach. Photo: Supplied.

Lindsay Smith continued the great work of Sefton and Gibson and, in 2004, was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to wildlife preservation through the Southern Oceans Seabird Study Association and two years later, the Serventy Conservation Medal by the Wildlife Preservation Society of Australia for outstanding wildlife conservation work involving seabirds.

Together, these Illawarra individuals often fought long and hard throughout their lives and rarely tired of opposing those who wished to destroy all that is beautiful in the natural and built environments of Illawarra.

You can observe the concern for all creatures by individuals like Alan Sefton while hearing him speak just after the silent start of a video available online, provided by the University of Wollongong and WIN TV.

The film demonstrates how much he cared and how widely Alan Sefton’s concern ranged – long before most realised just how great the impact of bushfires in urban Australia was likely to become.

Alan Sefton was also a pioneer of the fight to protect the koala population near Appin back in the 1970s and 1980s – something that, belatedly and only half-heartedly, is now a major concern.

The University of Wollongong holds an annual Alan Sefton Memorial Lecture to this day. And, unsurprisingly, with Sefton and Gibson in town, the Thirroul Public School’s four sporting houses were named Albatross, Gannet, Penguin, and Shearwater.