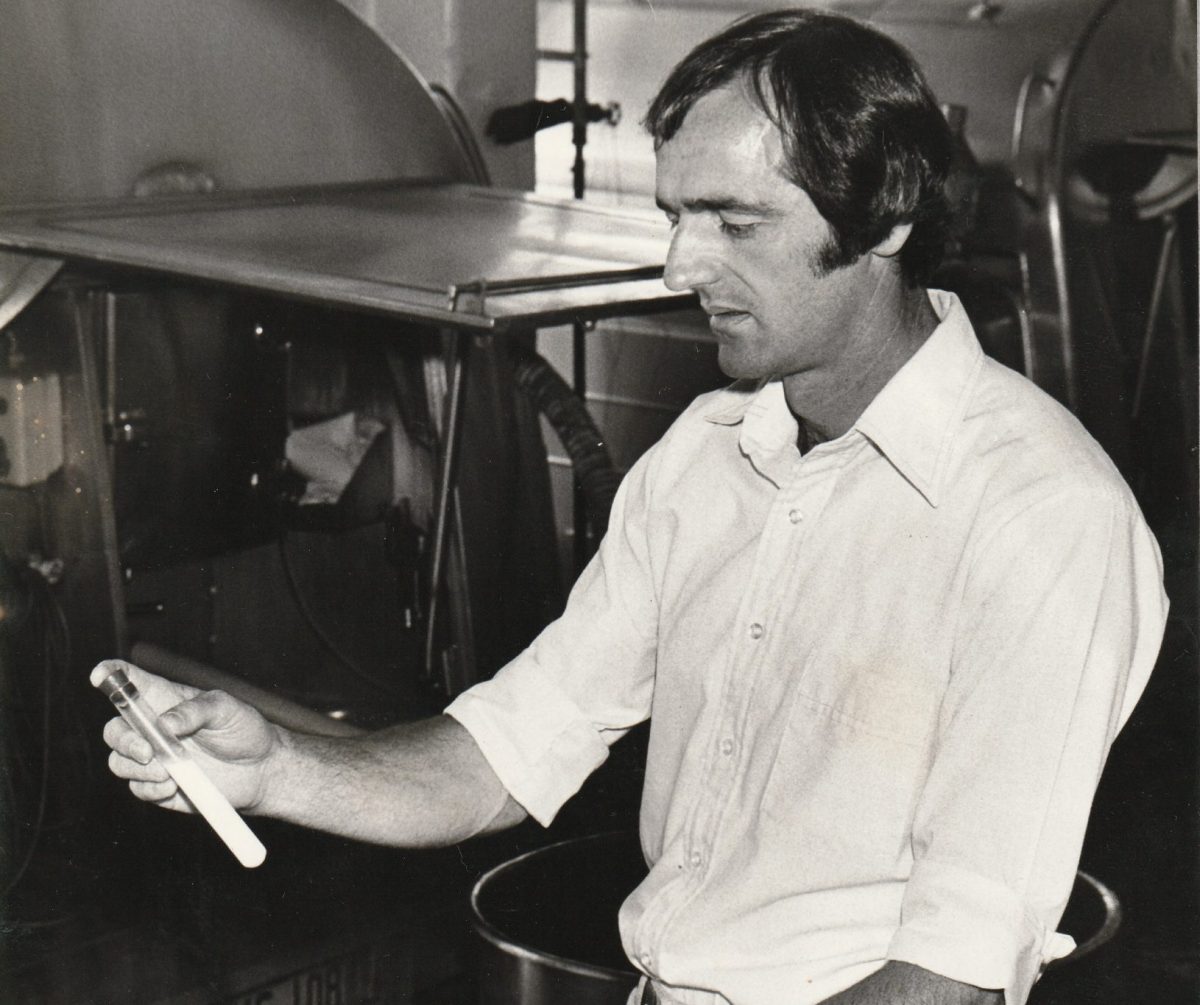

Pioneer dairy expert Geoff Boxsell in the laboratory in the 70s. Photo: Jamberoo Dairy Factory archives.

At 86, and with decades of dairy industry experience, Geoff Boxsell has forgotten more about butter than most will ever learn.

Geoff grew up 50 metres from the Jamberoo Dairy Factory, which his father Wallace managed. Having spent hours after school helping with the milking and watching as the butter churned, there was an inevitability about Geoff’s life’s work and passion.

“Every spare hour outside school was spent inside that building, watching, learning, absorbing,” family friend and fellow dairy expert Lynne Strong said in a speech earlier this year, when Geoff was awarded the 2025 Dairy Science Award. “By the time Geoff finished school, he already understood the rhythm of a dairy factory better than most adults working in one.”

That early knowledge formed the foundation he honed at Hawkesbury Agricultural College, where he graduated as dux with a Diploma in Dairy Technology in 1958.

Geoff worked at Jamberoo Dairy Factory from 1959 as the foreman and took over as a manager when his dad retired in 1970.

Under Geoff’s father, the factory proposed the first quota system to the Milk Board in the 1950s, to stabilise year-round dairy production. Geoff later refined the system into a model that was eventually adopted statewide.

“Jamberoo was famous for a few things, and that quota system was one,” Geoff said.

In NSW, Jamberoo Dairy Factory was famous for its high-quality butter, every churn of which was graded by the Department of Agriculture. For 15 years, they dominated the state and in 1976, their butter beat cheese, milk powder, ice cream and yoghurt from some of the country’s largest factories to claim Australia’s Supreme Dairy Product award.

Traditional methods were important at Jamberoo Dairy Factory, but that had to be balanced with innovation.

Never a big factory, it had to be smarter than the titans of its industry.

“Geoff once sourced a German evaporator sight unseen for what was then a fortune,” Lynne said. “It arrived in a million pieces. Geoff and the team assembled it themselves, and Nestlé selected Jamberoo to produce its premium condensed milk, which was also exported to Japan and Korea.”

Drawing on a scholarship trip to New Zealand where he studied cultured cream techniques, Geoff experimented with probiotic souring, carefully balancing acidity and pasteurisation to create a butter with remarkable depth and flavour — one that would go on to set an international benchmark.

But solidifying his legacy was a more rebellious innovation.

Geoff (pictured with his daughter Kate) accepted the 2025 Dairy Science Award. Photo: Lynne Strong.

It was around the time margarine companies rolled out Mrs Jones, a fictitious housewife who claimed Australians “deserved choice”.

“Margarine wanted to kill butter. The fictitious Mrs Jones had a real crack at it,” Geoff said.

“It was ‘bad for your health, caused high cholesterol and heart attacks’. But margarine is all fats and oils, a product made from scratching together other products. Cows made our product for us, and I reckon they did a great job.”

At a seminar held by the Dairy Industry Association of Australia, Geoff was struck by a talk from a University of NSW economics professor.

“He gave us a rundown on the margarine situation, and he probably didn’t put it quite like this, but what I took away from it was one message: if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em,” he said.

But Geoff wouldn’t simply submit to margarine madness. Instead, he and his trusted head laboratory technician, Kevin Richardson, innovated what would become a legendary experimental spread by blending cultured cream with sunflower and safflower oils.

Strictly speaking, it was against the stringent rules of the pure food act. But this hyperlocal product was quietly packed into tubs and sold only to the nearby farming community.

“We had been using cultured cream in all our churned butter since ’66, and that gave us a better quality butter to start with,” Geoff said. “Then we added vegetable oils and made this beautiful, spreadable product.”

It wasn’t butter, and it wasn’t margarine. So they simply called it “Stuff” — and the locals loved it.

Emboldened by the response and hoping to legitimise the operation, they sent a tub to the then Minister of Agriculture.

“We didn’t get a response from the minister, but one came from the Chief of the State Dairy Division. They said they’d revoke the factory’s dairy licence if I didn’t pull my head in — though it was a bit more ‘expressive’ than that,” Geoff chuckled.

“‘Stuff’ became part of local Jamberoo folklore,” Lynne said. “Official production stopped. But locally, the product lived on. Tubs of the spreadable butter circulated quietly among South Coast farmers, a kind of ‘black market’ dairy delicacy that spread like a dream straight from the fridge.”

As the industry consolidated, Jamberoo merged with Nowra to form the Shoalhaven Dairy Co-op. Eventually, the Shoalhaven, Canberra, Wollongong and Moss Vale factories all sat under Geoff’s oversight.

His leadership helped shape community life in Jamberoo, too. He helped found the golf club and write its ahead-of-its-time gender-equal constitution, and gave his time to everything from church service to floodplain management.

Though he retired in 2001 as joint company secretary of Australian Cooperative Foods, he never retired from contributing to the community, culminating in his recognition as Kiama Citizen of the Year in 2016.