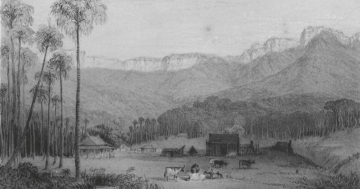

Doctors were few and far between in the early Illawarra so the humble leech often stepped into the breach to treat a variety of ailments. Photo: clu.

Tea tree and leeches. It’s an unlikely way to make a quid, but long before our dairy butter and black diamonds began to make big bucks for the Illawarra, tea tree wood and the medicinal leech were quiet little earners for the emerging local economy.

The first report of an Illawarra product being exported in exchange for money (apart from some smuggled cedar logs) comes from the diary of Lady Jane Franklin.

She was the wife of the very foolish Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) who froze himself to death trying to discover the illusive North West Passage.

When she visited in 1839, Jane Franklin noted there was much tea tree at the entrance to Lake Illawarra, some of which she claimed was profitably used in veneering and sent to England.

Sadly, Lady Jane’s casual remark is the only extant record of this pioneering trade.

But our trade in the medicinal leech is a completely different matter.

Today, leeches are simply curious (if rather annoying) blood-suckers which force the well-prepared to carry some salt on long bushwalks.

But our 19th century Illawarra ancestors knew better. Back then the unlikely leech was the height of fashion. What’s more, it was also health-giving and profitable.

Indeed, in the early 1800s there was actually such a thing as “leech mania”, and not only in the Illawarra.

So attractive were leeches thought to be that the fastidious women who adorned the Paris salons used to deck their dresses with embroidered leeches.

Yes, believe it or not, the leech was once a fashion statement, something that seems almost inconceivable today.

Leeches were once strongly associated with the cure of ailments and were therefore treated with great respect. Drawing off “bad blood” was believed to bring relief.

Everything from gout to nervous breakdowns was dealt with by the application of three or four bloodthirsty leeches to a strategic part of the anatomy. I have even read of syphilis being treated in this manner!

In the early Illawarra, doctors were few and far between and the humble leech often stepped into the breach.

I have seen no reference to the use of leeches by Aboriginal Australians but leech-craft has the longest colonial pedigree possible. The surgeons on the First Fleet set sail for Botany Bay with a supply of leeches on board.

Between 1827 and 1844, it is estimated that France imported more than 500 million leeches. In 1822 St Thomas’ Hospital in London used more than 50,000 leeches for medical bloodletting, over 31 times more than just four years previously. In 1824 alone, England imported five million. They sold for between one and two shillings each.

Perhaps the Illawarra was thus able to also get a piece of the action. Even as late as the 1920s, some Illawarra barbers were still dispensing leeches to customers.

A number of Illawarra chemists also dispensed leeches. The most famous of these was Courtenay Puckey (after whom Puckey’s Estate is named). Puckey is reputed to have employed people to gather them as well as collecting them himself.

A now deceased long-time resident once told me that the escarpment at the back of Thirroul was the favoured site in the Illawarra for leech gathering.

And, as it turns out, even this country’s original owners recognised Thirroul as a cornucopia for leeches.

As a letter written by Indigenous elder William Sadler in 1892 reveals, the word Thirroul is actually a misnomer: “My attention has been drawn to the ugly, meaningless name, ‘Thirroul’, recently given to the railway station previously known as Robbinsville. The original name of Robbinsville was ‘Throon’, and it was so called because the place was infested with mountain leeches. The name was impressed on children, as it was not considered safe to take them within the precincts of the leech dominions.”

It may interest readers to know that leeches are making something of a medical comeback. Occasionally, at least since 1985, some brave doctors have experimented with leeches to reduce swelling in some specialised operations.

The anti-coagulant in leeches (hirudin) is apparently also occasionally used when grafted veins fail to join properly. What’s more, in Wales at least, leeches are today being farmed for their hirudin which is then extracted and used in creams and ointments.

Who knows, the leeches still surviving on the escarpment at the back of modern-day Thirroul may once again become the focus of an export industry.