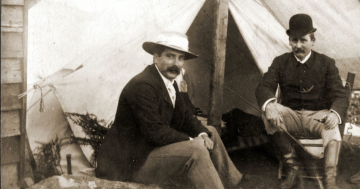

Mykolo Bialoguski, better known in his adopted home of Thirroul as “Dr Bottle of Whisky”. Photo: Supplied.

Mykolo (Michael) Bialoguski was the man who claimed to be primarily responsible for the defection of Soviet official Vladimir Petrov to Australia.

Bialoguski was born in 1917 in Kiev (then a part of Russia), but later moved to his Jewish parents’ homeland of Poland.

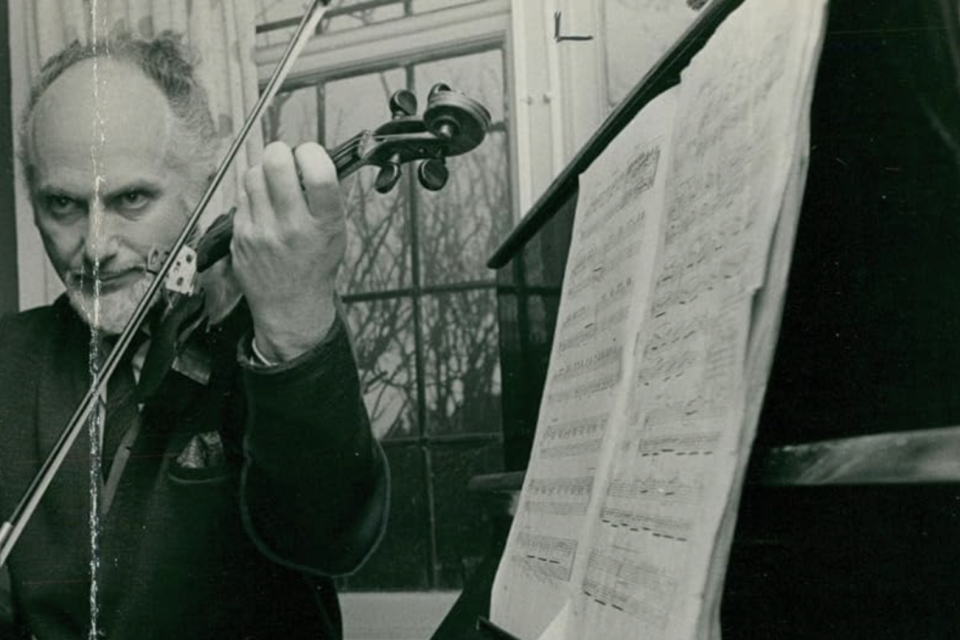

Bialoguski first studied violin at the Vilnius Conservatorium in Lithuania. He then enrolled in medicine at the Stephen Bathory University in Vilnius which was originally founded in 1759 by the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania.

After the invasion of Poland in 1939, Bialoguski claimed he was arrested for protesting the Red Army’s occupation, but somehow successfully escaped and arrived in Sydney in 1941.

He enlisted in the Australian Army Medical Corps and by the end of the war, on an ex-serviceman’s scholarship, was enabled to obtain a medical degree from Sydney University.

He became a GP in the then white-bread town of Thirroul, where his more xenophobic patients found foreign names hard to pronounce and dubbed Dr Bialoguski “Dr Bottle of Whisky”.

But for Bialoguski medicine was really only a sideline, for his main interests in life were music and anti-communist espionage.

In elections in the 1940s the Bulli electoral district gave the communist candidate more votes than the Communist Party received in any other electorate in NSW.

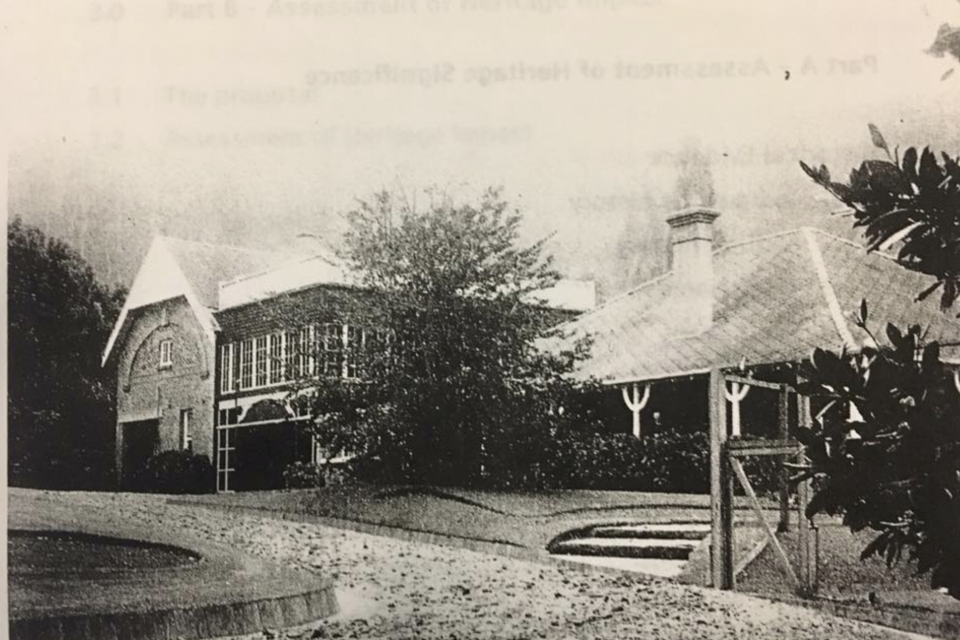

But to Bialoguski these local people were small fry – and anyway, he was busy renting and entertaining in “Ballinderry” – then Thirroul’s only truly grand residence located on Ford’s Road.

Here the rabid anti-communist Bialoguski and another anti-communist emigre doctor (who bought Ballinderry in 1947) renamed the house Massandra after Tsar Nicholas II’s holiday home rather than the dacha of Josef Stalin who was at the time still often celebrated locally as the great ally of Australia against the fascist aggression of the Nazis.

During regular trips to Sydney to both play at or listen to classical music concerts, Bialoguski got to hobnob with other devotees of classical music – including Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov who had been appointed to Australia as third secretary at the Soviet Embassy.

Petrov, although of humble peasant background, had rocketed to success after joining the Soviet spy organization, the OGPU, in May 1933. He was subsequently admitted to the Special Cipher Section.

Bialoguski, however, was not only the opposite of a communist but seems to have also only been mildly interested in being a doctor – instead maintaining keen interests in music, espionage and anti-communism. Consequently, he offered his services to Australia’s Commonwealth Investigation Service in 1945, assuring the authorities he could help them infiltrate the pro-Russian community.

Using the codename Grigorii, Bialoguski posed as a communist sympathiser and infiltrated the Russian Social Club in Sydney which is where he met Vladimir Petrov in 1951.

The two shared several interests – with Petrov being rather keen on prostitutes and, fortunately, Bialoguski seems to have known where to find them for him.

Coincidentally, Petrov had for a time once worked in the Polish Embassy as a colleague of Alexandra Kollontai the famous Russian exponent of free love – but seems to have understood that in a capitalist country like Australia he might have to pay.

Bialoguski became sufficiently trusted to become medical adviser to Petrov and other Soviet diplomats and this seems to have enabled him to help Petrov see the possibility of a lucrative defection to Australia – that is, if Petrov was willing to reveal some of the Russians’ secret codes, cyphers and international agents.

Bialoguski eventually engineered Petrov’s defection indirectly by using an eye surgeon, Dr H C Beckett, through whom ASIO was able to offer Petrov a firm and attractive proposition.

With all the publicity the Royal Commission into Espionage received in the aftermath of the Petrov defection, Bialoguski might well have hoped to become celebrated as a sort of top secret agent in the style of James Bond.

But Bialoguski’s book, The Petrov Story (made into an American TV documentary in 1956), appeared the year after he divorced his second wife.

Sadly for Bialoguski, his ex-wife proved willing to talk to the Sydney press and made salacious allegations. This bad press and other matters meant Bialoguski failed to be given a permanent job with ASIO.

It would seem that quite a bit of whatever money Bialoguski had previously made as a spy was likely chewed up in divorce and libel proceedings against his second wife. Worse, the bad publicity seems to have caused his previously lucrative Macquarie Street Sydney medical practice to also decline.

In 1964 Bialoguski left for England with his third wife. There, even though back in 1949 Sir Eugene Goossens had invited him to accept a position as a violinist in the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Bialoguski’s pursuit of a fully professional musical career did not go as well as he hoped and he seems to have again mostly had to rely on medicine for a living.

Bialoguski (aka Thirroul’s “Dr Bottle of Whisky”) died in 1984 and his death seems to have gone almost completely unheralded in the Illawarra.