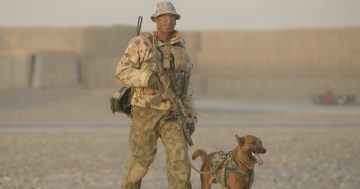

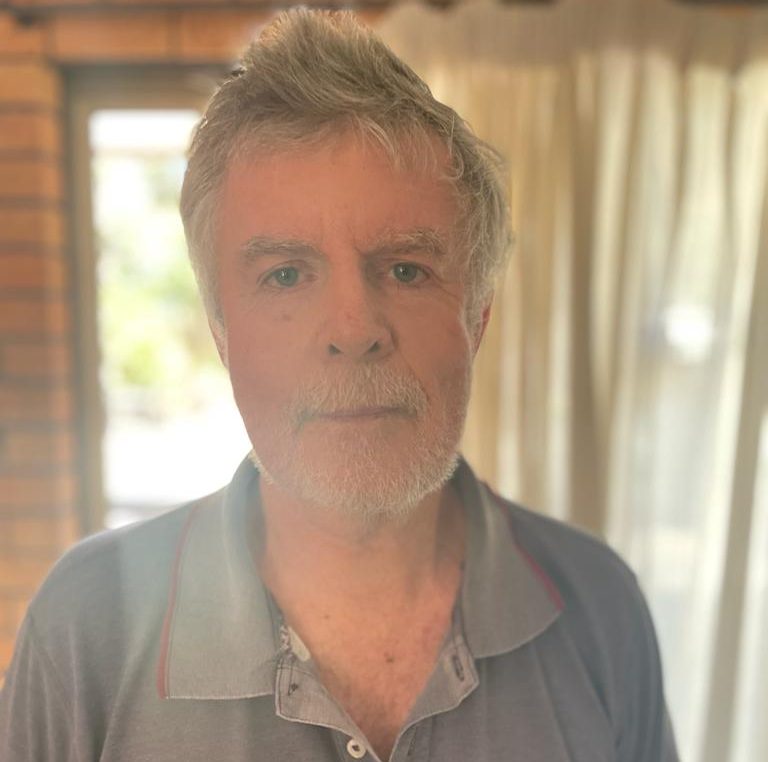

Former radio host and professional broadcaster Heath Piper has found a higher purpose. Photo: Heath Piper.

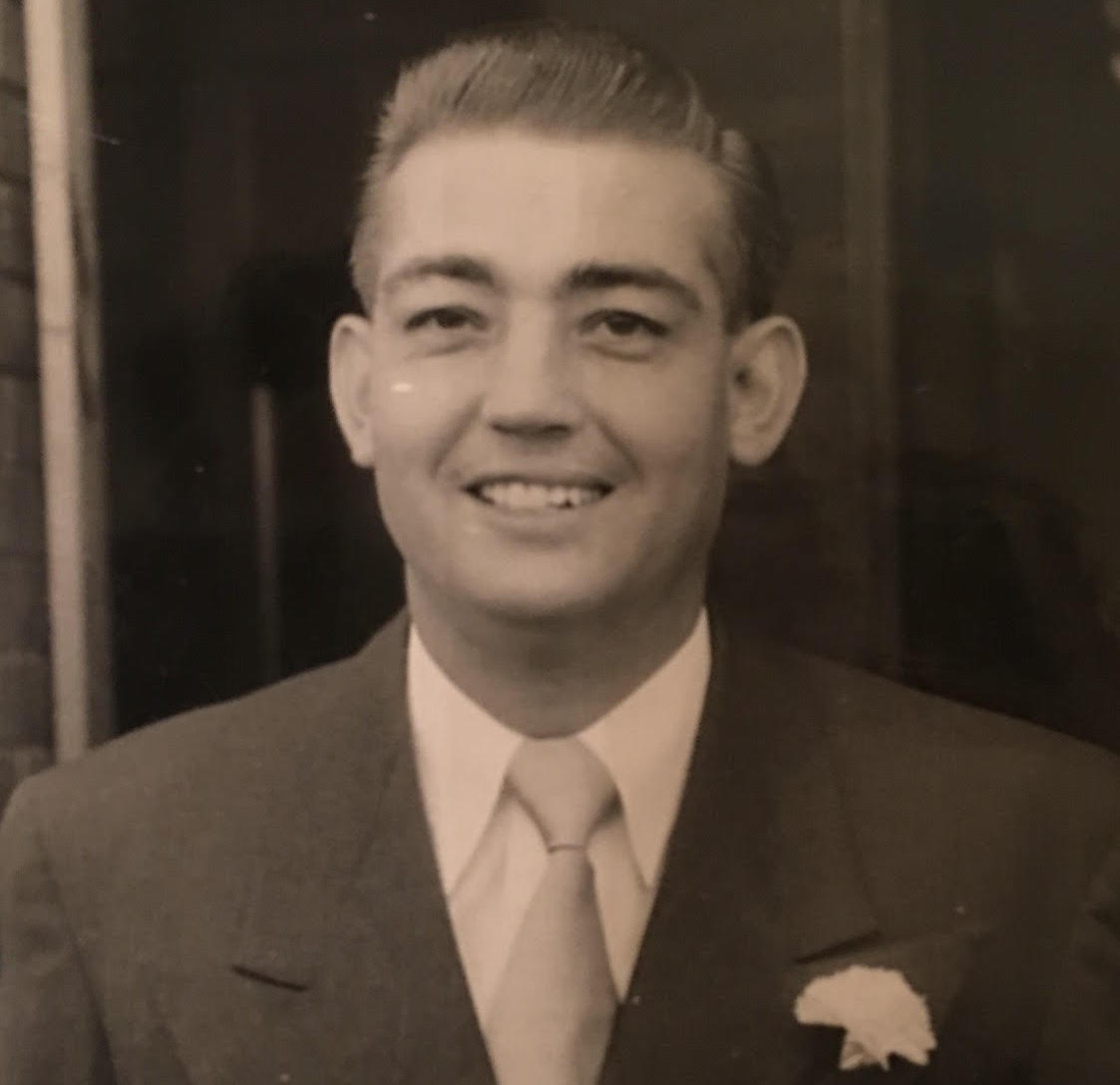

Heath Piper was in the process of renovating the family home in Scarborough when he came across a photo of his beloved “Pa”.

When his son wanted to know more, the professional broadcaster, who had spent more than half his life talking for a living, was lost for words.

“It’s a hard concept to explain to anyone, let alone a five-year-old. When I was his age, my Pa was my whole world,” he says.

“You’d hear stories on the grapevine about the things he had seen in his lifetime – like the atrocities of war and losing friends at sea. But we’d go to his house in Beverly Hills and he was always so affable.

“My Pa was the family storyteller. He was articulate and humorous and in fact, he was the reason I went into radio and created a comedy show with my best mate. He taught me how to tell a good story.

“But try as I might – and I really did try – I couldn’t remember his stories, and even if I could, I could never tell them the way he did.”

It was the seed that propelled him to start Playback Interviews, a service people can commission to capture modern-day memoirs of their loved ones, by their loved ones.

The service has struck such a chord across Australia that Heath is booked out for 2023. The privilege is not lost on him.

“It has been a struggle to get to a place in my life where I feel I’m doing something that I’m good at, that’s adding value to people’s lives,” he says.

“And only now do I realise how much of my life has been to find this.”

Inspiring from beyond the grave – Heath Piper’s “Pa” was the reason he got into radio and now, Playback Interviews. Photo: Heath Piper.

The idea is not to distil a person’s entire life story into a couple of hours of audio. Heath’s process instead creates what he calls “audio art”.

He records stories that capture a person’s “human essence” in a way that can only happen when they’re told by the unique individual themselves. For authenticity, he starts recording the moment he arrives at their house.

“The family is listening, going, ‘There’s the front door slamming … that’s granny walking over the wooden floorboards’ – nuanced things only a family would understand,” he says.

“I’ll cut the ‘ums’ and ‘ahs’ out mostly, maybe my own questions, but I never edit content out. That’s not my place.

“I do have a responsibility here because I know these stories will be played when the person’s gone. I have to get it right – a tone that’s life affirming, entertaining and true. I want them to be proud of their story, and the way they’ve told it.”

Heath has gotten the process down to a fine art. By the time he arrives at a person’s home, expectations are set and the interviewee and their families are well prepared for the process and outcome. They’ve had time to mull over the questions, and generally require less than two hours of actual recording time.

It’s important to establish a level of trust because the questions are deeply personal – like, “What are the things you think about most when you’re alone?”. And despite Heath being a stranger, or perhaps because of it, their stories start spilling out.

It’s meaningful, important work and by nature, has had a profound impact on the creator.

“When I started, I wasn’t prepared for how profound it was going to be cause I came from a comedy radio show,” he says.

“Sometimes, they’re crying tears of the deepest sorrow for a life partner that they’ve outlived and you can see the years of loneliness in that one moment. I am quite sure I’ve developed a whole new heart string muscle in the last few months, in order to support them in that moment and make space for them to feel it.

“At the same time, they’re beautiful, because they’re epic love stories. And I get to watch their faces light up when they recall how they first met the love of their life, dates they went on before they had kids, or perhaps the joy of raising children, which they invariably say is the best time of their lives.”

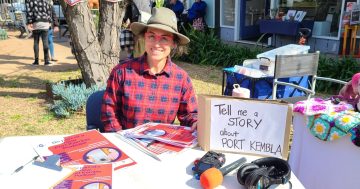

“Wingy” aged 71 years, is one of Heath’s subjects. Photo: Heath Piper.

Playback Interviews allows people to avoid realisations like Heath’s, about his Pa.

“On my radio show we’d interview the celebrities of the day – Ricky Martins, Kim Kardashian and so on. I’d say to my co-host, ‘My Pa has way better stories than these celebrities getting on air, we should get him on and do regular segments’,” he says.

“We never did and then he passed away. And it was a big regret.

“If my Pa was alive and I got to ask him one more question, I would just say, ‘What did it all mean to you, Pa?’. That’s it. And then he would talk.”

For more information visit Playback Interviews.