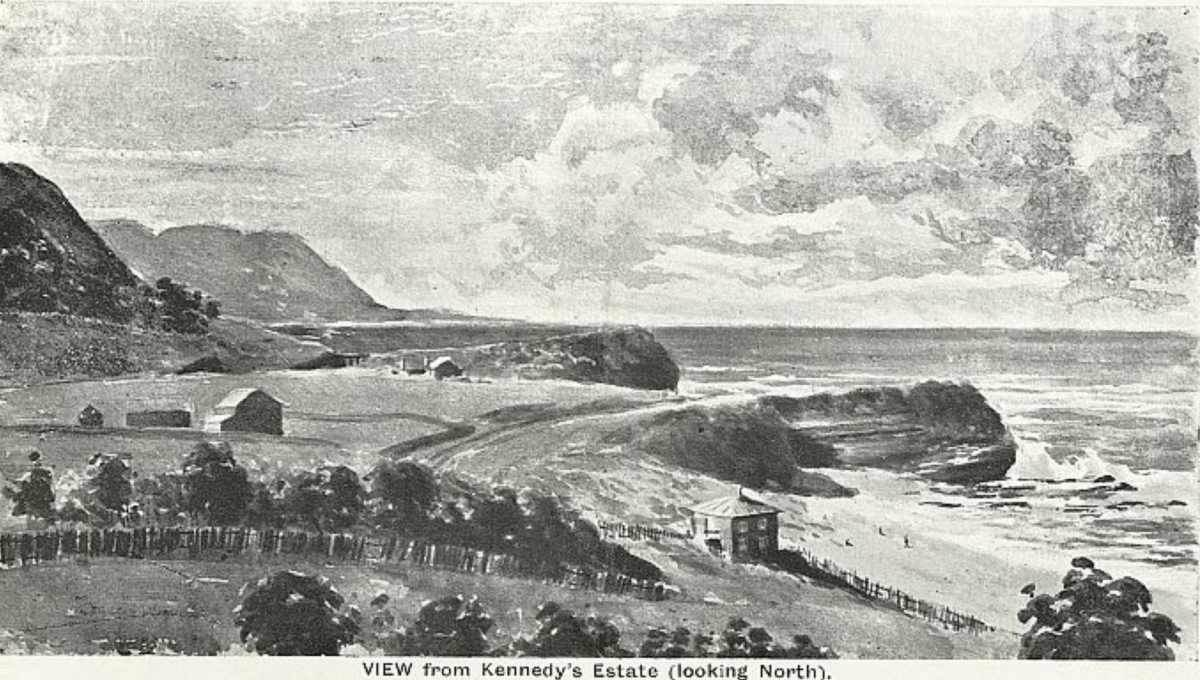

A spectacular image of undeveloped Austinmer from the Slade & Brown (Hardie & Gorman) 1906 real estate booklet used to sell the estate on Kennedy’s Hill at Austinmer. Photo: Supplied.

By the end of the 1880s, both Thirroul (then known as Robbinsville) and Austinmer began to be distinguished from the general area known as North Bulli.

Austinmer was the bigger village, with its own mine, associated cottages, a handful of stores, a progress committee and even a non-waterfront sleazy Moore Street bar opposite the railway station before it promptly burnt down.

Thirroul had only very slowly begun to develop when some Bulli miners decided it was preferable to live at some distance from their workplaces at Old Bulli and Austinmer colliery (still then called North Bulli mine).

A few hardy tourists visited the already famous Bulli Pass area before the opening of the rail line to Sydney in 1887. The attractions were “the fern gullies, mountains and safe bathing places”, according to a newspaper correspondent.

Back then the only small scale tourist accommodation was at George Whitford’s big house on the site of today’s Ryan’s Hotel. The opening of the rail line from Sydney, however, looked like it would soon make more large-scale tourism possible and by the end of the decade, Thirroul pretty smartly had both a post office and a public school.

With the onset of the major early 1890s economic depression, Austinmer was still the slightly large village and might have been thought to be slightly better placed to survive the crash and later emerge as a popular seaside resort.

The closure of the Austinmer mine put paid to such dreams.

Before the economic crash there had been dreams aplenty. One delusionary visionary claimed hot-air balloons and a cable car climbing the escarpment would soon be servicing both towns with its opening ceremony featuring Enrico Caruso in person singing Funiculì, Funiculà.

Economic recovery was slow but by 1900, leafy Bulli Pass and its lookout remained the major attractions and Thirroul had its own progress committee and a considerable number of guesthouses.

Austinmer, however, remained the proverbial deserted village while land in Thirroul was being subdivided and Sydneysiders built holiday cottages on the newly created blocks.

It took until 1906 before a substantial subdivision took place on Kennedy’s Hill at Austinmer. The land was quickly snapped up after a savvy Sydney real estate agent offered free rail tickets for anyone saying they would bid at the auction.

Thirroul Beach in the 1920s. From the collections of Wollongong City Libraries and the Illawarra Historical Society – P10291.

Together both Thirroul and Austinmer developed a reputation as the premier seaside resorts in NSW as sea bathing was legalised and became a very popular craze. Even the NSW Premier William Holman purchased land at Thirroul and became vice president of Thirroul Surf Club.

Thirroul went ahead in leaps and bounds. It had its own coal mine in 1905, the first King’s Theatre opened in 1913 and the Thirroul School of Arts was established the same year.

A rough golf course stretched out towards Bulli Point by 1914 and the railway depot and marshalling yards arrived in 1915 when duplication of the railway line took place – something that encouraged even more tourists. Austinmer could match none of this.

The original rather small wooden “Outlook” guesthouse had been built in 1911. A progress committee was attempted in 1914 and agreed to hire a lifesaver for the beach. The committee initially unsuccessfully lobbied to reclaim all of the beach foreshore from a famous Sydney family of legal eagles, but had more immediate success establishing a rough walking track up towards Sublime Point.

These facilities benefitted Thirroul as much as Austinmer and many Austinmer residents remained bitter, for they considered the Thirroul School of Arts building near the railway station (established in 1913) was too far from Austinmer and some Austinmer residents had contributed to its construction.

In 1919 Thirroul’s development was furthered by construction of the Vulcan Firebrick Company’s works. But this did not prove good for the tourist trade. Coal-fired kilns created considerable pollution and the new railway depot smack in the middle of the town was another ugly and noxious blot on the town’s resort status.

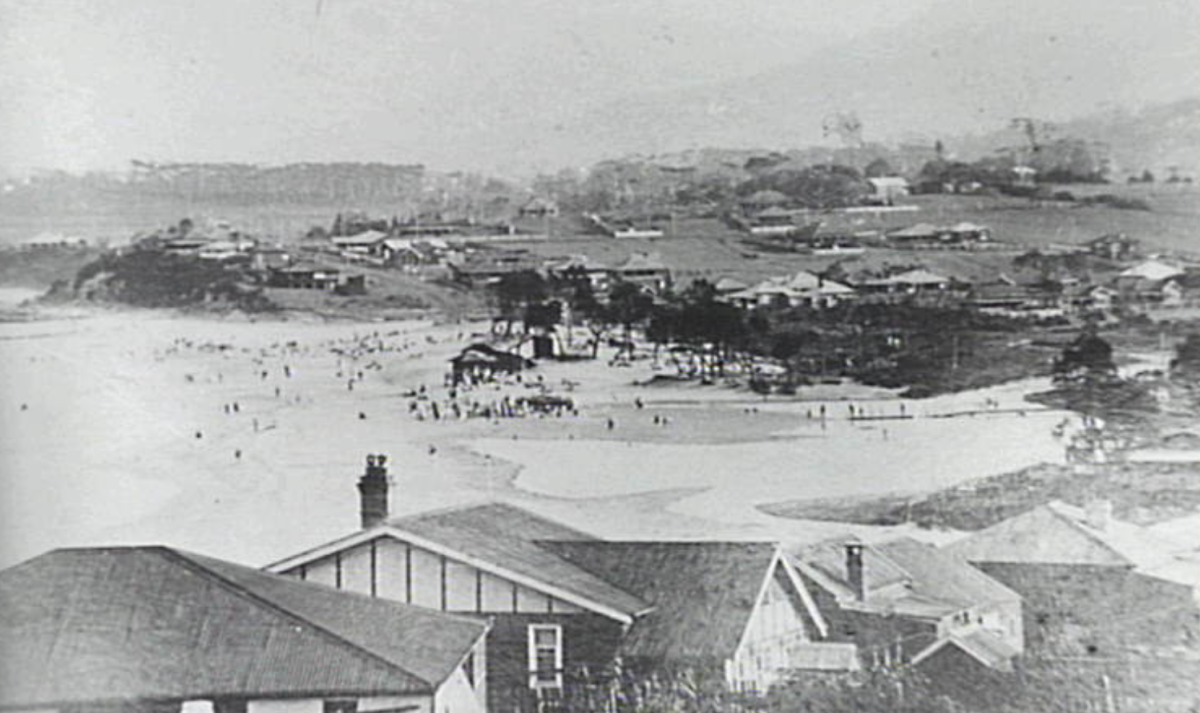

Two panoramic views of Austinmer beach in the late 1930s when its Pavilion, rock pool and promenade had got just a little bit too popular. Photo: Supplied.

The miners from Thirroul’s Excelsior Colliery also blackened the tourist scene by walking home from the pit covered in coal dust before washing facilities were belatedly made available by the mine owners in the mid-1920s.

All this was to Austinmer’s favour and Thirroul was fast losing out in the tourist stakes.

Even worse, Austinmer soon began to hail itself as “Riviera of NSW”.

The establishment of the Thirroul open-air Dancing Arena in 1919 and the fine Arcadia Theatre (with its polished native timber interiors) in 1923 did little to stem the drift to Austinmer as, being located on the northern side of town, both were within easy walking distance of Austinmer.

What is now Thirroul’s Anita’s Theatre (the King’s Theatre) opened in 1925 even closer to Austinmer and became exceedingly popular.

The smaller physical scale of tourist development in Austinmer and the retention of its village atmosphere worked more and more in Austinmer’s favour and by 1930, Austinmer had become the premier coastal resort.

Thirroul residents had constructed a rock pool on South Thirroul beach in 1923 but it paled in comparison to the grandiose scheme of Councillor Clowes of Austinmer. He spear-headed plans for development of the still marvellous rock pool and promenade at Austinmer in the late 1920s.

It was completed in December 1930 at the then fabulous cost of £30,000. It was the icing on the cake in terms of attracting tourists to Austinmer. Its construction even ensured Austinmer would survive as a tourist resort even after the Great Depression hit so soon after its construction.

If there is a lesson to be learnt from the history of tourism in the northern Illawarra it might be that large scale development is not always the key to success if it mars the natural beauty that attracted tourist in the first place.

Tragically because I grew up in Thirroul and still live there rather than in Austinmer, I’ve clearly long been a fool to myself and a burden to others.

Thirroul is nearby – but, sadly, though closely within reach, one has to accept the tragedy of living just one suburb south of The Promised Land.