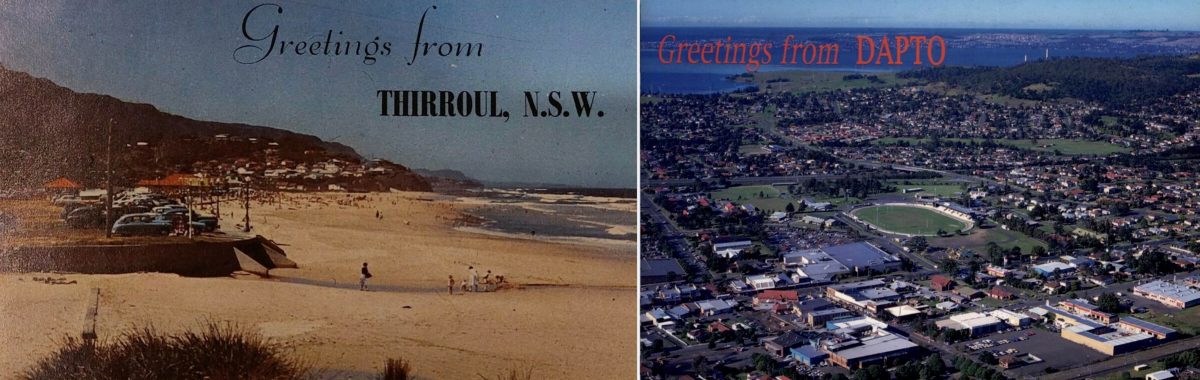

Back in the 1800s the place to be in Wollongong was Dapto – Joe Davis thinks there’s a good chance that what was old will become new again. Photo: Joe Davis.

Back in the 1830s, European Thirroul had not been invented and was not even a twinkle in Dapto’s eye.

Despite Thirroul today possessing a “McCauley Street” and a “McCauley Park” and a “Samuel Close” (named after the McCauley patriarch Sam) back in Samuel McCauley’s day it didn’t exist.

The McCauleys lucked out again when Thirroul first got named Robbinsville (sometimes spelt “Robinsville”) because a wily little operator named Frederick Robins worked up a real estate scam by marrying one of the daughters of old Sam McCauley.

Meanwhile, Dapto was blessed by having a different Robins family early give their name to Robins Creek at Dapto – a tributary of what in 1840 the Sydney Monitor described as “the beautiful river known as the ‘Mullet Creek’” with acreage “far-famed for its fertility”.

Even more surprising, the first person to purchase land in Thirroul was actually not the McCauleys but the Dapto stonemason, James Tweedie, who in 1837 chose not to live there.

Today one of Thirroul’s few claims to any historical importance is that in the winter of 1922 a tubercular novelist named D.H. Lawrence (author of the once scandalous Lady Chatterley’s Lover) once spent a very long weekend in Thirroul knocking up a potboiler of a novel called Kangaroo.

But it was actually the barber, George Lachlan, only recently relocated to Thirroul after years servicing the hair of the good folks of Dapto and Mullet Creek, who provided Lawrence with some Illawarra local detail for his novel.

Further, even “Wollorowong” – the last of Thirroul’s big guesthouses – was purpose-built for (you guessed it ) the long-term one-armed Dapto Postmaster, Mr William Mead, who had lost his arm as a teenager in an accident at George Brown’s Steam Mill at Brownsville.

Better still, a Mr Frederick Gibbins (born at Dapto in 1841) constructed a fine house, now with State Significant Heritage listing, at 171 Wollongong Road, Arncliffe, to which he gave the Indigenous name “Dappeto” after his birthplace.

Gibbins’ spelling seems to suggest that the Indigenous word from which the place-name “Dapto” derives may have originally had three syllables instead of two – much like Thirroul’s “Dthirrawell”.

Frederick Gibbins was the eldest son of ex-convict John Gibbins (transported in 1829 on the Claudine), and free-born Ann Meredith, daughter of the Liverpool chief constable.

John Gibbins was the butcher servicing the stores in the Government Stockade attached to the road building convict gang which started at Mt Keira near Wollongong and progressively worked its way south to Dapto and its important thoroughfare, Bong Bong Road.

Moreover, Frederick Gibbins’ daughter Ada (1878-1951) who was married at “Dappeto” in 1907 to David George Stead (1877-1957) became the stepmother of Australia’s truly great Marxist-Feminist novelist, Christina Stead (1902-1983) – thus putting D.H. Lawrence (who, puzzlingly, called Thirroul in Kangaroo “Mullumbimby”) somewhat in the shade.

So the simple message is that so important was 19th century Dapto that even George Brown (of Brownsville fame) in 1834 gave up his “Ship Inn” (a sleazy waterfront bar fronting Wollongong today’s Millionaires’ Row at Belmore Basin) in order to set up a new pub in the then more salubrious surrounds of Mullet Creek at Brownsville.

Moreover, by the 1890s the Dapto Railway Station was by far the most profitable on the entire South Coast Line because of the huge volume of materials being shipped there to service the smelting works at Kanahooka.

Early Brownsville and Dapto also once left Thirroul for dead in the tourist stakes and George Brown’s son (also named George) operated steam launches from Mullet Creek to take tourists on joyrides down to Lake Illawarra and on to Gooseberry Island for wild all-night dance parties.

All Thirroul could offer was a hot and sweaty hike up Bulli Pass to the lookout – at least until the ban on daylight surf bathing was overturned in the first decade of the 20th century.

Thirroul wasn’t even covered by a shire council until 1906 whereas Brownsville and Dapto, from 1859, were the twin hearts of the Municipality of Central Illawarra.

That council even included environmentalists such as George Brown’s son, John, who early endeavoured to have Gooseberry and Hooka Islands preserved as nature reserves.

Thirroul, on the other hand, had started to attract campers to its heavily wooded beachfront but then allowed them to chop down all the coastal trees for their campfires.

Dapto, instead of Wollongong, was thus the real centre of “Central Illawarra”.

My guess is that it will soon be very much a case of “Dapto, Brownsville, Kanahooka/ Here we come/ Right back where we started from” – for the westward march of the area will, in just a few decades, house some 60,000 extra residents and so will make Thirroul’s housing infrastructure (which will be lucky to ever house 10,000) look miniscule.

Better still in 1988 my sister-in-law convinced me that the Illawarra heritage dwelling most suitable as a wedding venue was Dapto’s wonderful “Horsley Homestead” which, back then, still looked west to empty cow paddocks that today are chock-a-block with new dwellings.

So it’s hard not to disagree with the singer-songwriter awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature when back in 1964 he declared that “the present now will later be past” for in 2025 “the times” in Illawarra almost certainly “are a-changing”.