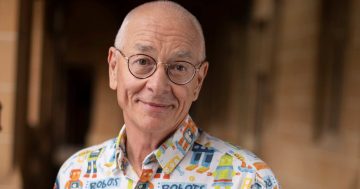

The Shepherd Centre’s Tiffany Slater and the hospital staff in Japan who are working with her. Photo: Supplied.

Tiffany Slater can recall exactly the moment in high school that set her career path.

“It was Year 12 at Wollongong’s Smith’s Hill High School when a friend and I were going through a university degrees guide when she emphatically said I want to be a speech pathologist,” Tiffany said.

Her friend’s newfound ambition lasted about a minute but Tiffany liked the idea and pursued it with a passion that has never wavered.

Now, 20 years later, Tiffany heads the Shepherd Centre’s plan to export its highly successful early intervention program for babies and children with hearing problems to Japan.

“It’s been a project 10 years in the making, and we are now at the stage where we are holding training sessions with clinicians at Shizuoka General Hospital in Shizuoka Prefecture southwest of Tokyo,” said Tiffany.

The Shepherd Centre is recognised as a world leader in pediatric hearing loss programs which have supported thousands of families in the past 50 years.

“We are incredibly lucky in Australia to have a screening program days after birth that can detect hearing difficulties that can be better managed with an early response whether it be by cochlear implant, hearing aid or signing,” Tiffany said.

She is based at Wollongong’s Shepherd Centre where she leads a team of highly trained speech pathologists, audiologists and counselors to support families through the process.

“Japan also has a screening program for newborns but the ability to apply best practice in early intervention programs is lacking due to outdated training,” she said.

“They don’t have audiologists simply because that qualification doesn’t exist. The speech therapists and pathologists in hospitals do their best but they are not all degree trained.”

The uptake of cochlear implants is also much lower than in many western countries.

Australia has a 90 to 98 per cent take-up of cochlear implants compared to the 50 per cent uptake in Japan.

And the implants are not done until the child is one or two years old, whereas in Australia it is at six months.

“Our policy on when cochlear implants should be done is the sooner the better because the auditory system changes very quickly and training has to keep up,” Tiffany said.

The need to improve Japan’s outcomes for children and their families is also evident in statistics that show by age four or five their children with hearing difficulties are going to special needs schools, whereas children in Australia at that age are considered capable to enter mainstream schools.

Tiffany said the bottom line was that the choice of therapy in Australia and Japan was left to parents and she agreed with that.

“As a clinician, I feel the cochlear implant delivers the best outcomes for children.

However, my speech pathology heart and background says as long as children have a really robust language and communication system, that is what matters,” she said.

Tiffany is extremely proud of her four-person team who have overcome some difficult barriers in terms of language and cultural issues. Their remarkable determination and drive has made significant inroads.

“The language barrier means we have to work with interpreters who, in turn, have to pass on our instructions to clinicians who then have to explain it to parents, so yeah, it’s been fun,” she said with a laugh.

With the feet-on-the-ground program underway, Tiffany is sensing a mood for change in Japan.

“I think it’s coming from the high-ranking speech pathology specialists who attend conferences all around the world and see what countries like Australia are achieving,” she said.

“I’m incredibly proud to export our knowledge to Japan in skill-building for systemic long-term change that will continue long after we are gone.”

All expenses for the project have been met by government and private grants in Japan.