Distinguished Professor Noel Cressie and Associate Professor Andrew Zammit Mangion from UOW’s National Institute for Applied Statistics Research Australia (NIASRA) conceived WOMBAT, later joined by senior fellow Dr Bertolacci and a team of researchers. Photo: UOW.

Once exclusively applied to the beloved and iconic Australian animal, the word WOMBAT is now making ripples on the global scientific stage for something else entirely – as a valuable tool in the fight against global warming.

WOMBAT (the Wollongong Methodology for Bayesian Assimilation of Trace-gases) is a framework developed by a team of predominantly University of Wollongong (UOW) researchers, used to estimate the flux of carbon dioxide (CO2) at the Earth’s surface on a global scale.

Understanding CO2 flux is critical to global efforts of mitigating atmospheric CO2 and global warming.

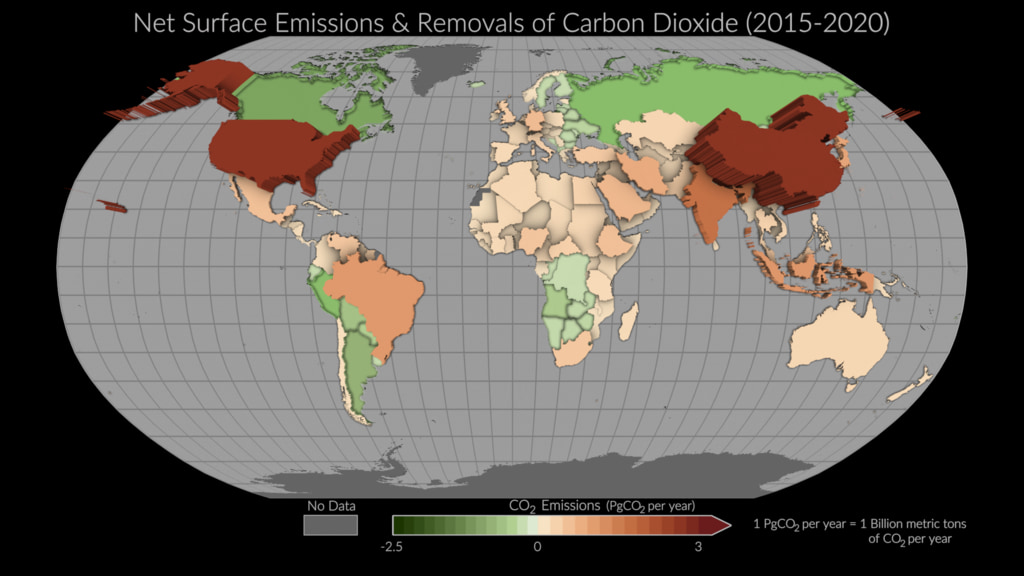

An international study led by NASA, which included the WOMBAT team, resulted in this map that illustrates mean net emissions and removals of carbon dioxide from 2015 to 2020, using estimates informed by its OCO-2 satellite measurements. Image: NASA Scientific Visualisation Studio.

Earlier this year WOMBAT was employed in an international study to track carbon dioxide emissions for more than 100 countries around the world and was featured on the cover of Significance magazine.

More recently, after publishing a paper about WOMBAT in the Geoscientific Model Development journal the research team won three awards at the international 2023 Joint Statistical Meetings (JSM), held in Ontario, Canada.

The Outstanding Statistical Application Award and the Statistics in Physical Engineering Sciences Award from the American Statistical Association, and the Mitchell Prize from the International Society for Bayesian Analysis are among the most prestigious in the field of applied statistics. Winning one award is a huge achievement – winning three is exceptional and a first since the establishment of the most recent award in 2015.

WOMBAT was conceived in 2015 by Associate Professor Andrew Zammit Mangion and Distinguished Professor Noel Cressie from UOW’S National Institute for Applied Statistics Research Australia (NIASRA).

“I was told that many people had attempted to solve this problem and failed after several years of trying, and it was made clear to me that it was a big risk going down this research path,” Associate Professor Zammit Mangion said.

“Eight years later, winning these prizes is testament that we managed to push the boundaries of what was thought possible when estimating and quantifying uncertainty in the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide from satellite data.

“It’s a privilege for our team to be acknowledged in this way by the international scientific community.”

WOMBAT arose because the two academics, who shared an interest in atmospheric trace gases such as carbon dioxide, wanted to develop statistical methodology for finding where trace gases come from and go to on the Earth’s surface.

“We were seeing many impressive techniques for estimating the ‘sources and sinks’ (flux) of a trace gas like carbon dioxide from satellite data, but we wondered whether we could improve the uncertainty quantification aspects associated with these techniques,” Associate Professor Zammit Mangion said.

UOW School of Mathematics and Applied Statistics senior research fellow Dr Bertolacci joined the team in 2019, helping design the methodology behind WOMBAT and writing most of the software that powers it.

“When you’re trying to estimate something over the whole globe, there is a lot of uncertainty. And what we do that most systems don’t do is try and quantify the uncertainty at every level, from the measurement all the way up to our prior scientific understanding of where those sources and sinks should be,” he said.

“The most challenging part was that we had to integrate multiple disciplines together … from atmospheric chemistry through to statistics and a bit of geophysics. And once you put all of that together, there’s just a lot of complexity that we had to work through.”

The team also includes three atmospheric chemists (Associate Professor Jenny Fisher, UOW, Dr Ann Stavert, CSIRO, and Professor Matthew Rigby, University of Bristol) and UOW IT specialist Dr Yi Cao.

An atmospheric scientist from UOW’s School of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Sciences, Associate Professor Fisher’s role in the project was to help the team use the atmospheric model that linked the fluxes to the satellite observations.

“The really big problem that everyone’s interested in is how much CO2 is coming out of the Earth’s surface, whether that’s from natural sources or from human activities like burning fossil fuels,” Associate Professor Fisher said.

“It would be great if we could measure those fluxes directly, but what we measure is the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. By the time we get to the satellite where we’re making that measurement, all of those different sources have mixed, they’ve travelled really far downwind, and we need some way to go from the concentration in the observation back to where that source originally came from. For that we use atmospheric transport models and that’s really where my part of the project linked in.”

For more information visit the University of Wollongong’s Global CO2 Flux webpage.